by Karen Cook

Published March 2, 2020

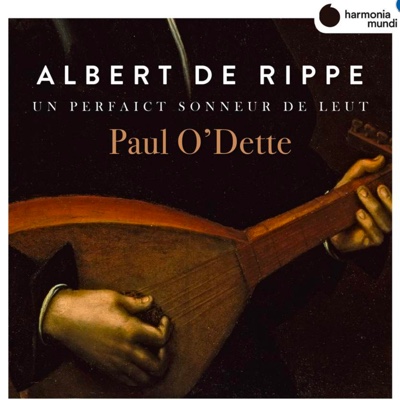

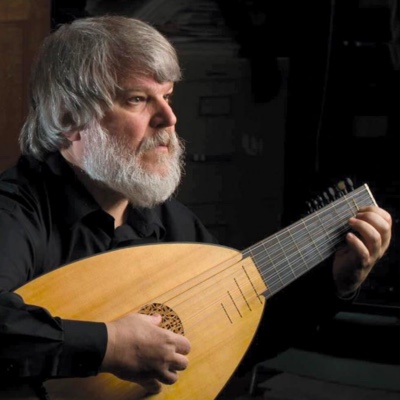

Albert De Rippe: Un Perfaict Sonneur de Leut. Paul O’Dette, lute. harmonia mundi HMM 902275

Playing the lute was more than just a past-time in early 16th-century Italy; it was a highly esteemed courtly activity. Famous lutenist-composers such as Marchetto Cara and Bartolomeo Tromboncino flourished at the Este court in Mantua. But the Mantuan-born lutenist Alberto da Ripa is much harder to trace in his earlier years. What we do know is that by the time he was 28, he had left for France, where François I paid him double the annual salary of the other lutenists and lavished him with gifts of money and land.

Albert De Rippe, as he became known, rose through the ranks, performing in the highest echelons of society (on one occasion he joined Francesco da Milano in playing for Pope Paul III). Praised for decades by writers and musicians across western Europe, he was exceptionally well known in his lifetime. All the more surprising, then, to realize that only three of his works were published while he was alive; the rest of his output was printed posthumously under the direction of a former student, Guillaume Morlaye.

Albert De Rippe, as he became known, rose through the ranks, performing in the highest echelons of society (on one occasion he joined Francesco da Milano in playing for Pope Paul III). Praised for decades by writers and musicians across western Europe, he was exceptionally well known in his lifetime. All the more surprising, then, to realize that only three of his works were published while he was alive; the rest of his output was printed posthumously under the direction of a former student, Guillaume Morlaye.

Like other composers, De Rippe’s work centers on the most popular genres of his day: fantasias for both lute and guitar, dances, and intabulations of vocal works, almost entirely French. But in significant contrast to his peers, he creates much greater technical challenges: five- and six-note chords instead of the typical three, sweeping arpeggiated chords; long, singable phrases; and a wide palette of tone colors. Because of these technical and compositional attributes, De Rippe’s music tends to stick out from the crowd. That’s why, Paul O’Dette explains in liner notes, a number of the dances and the final guitar fantasia are included on this album, despite not having been attributed to him.

If anyone should know how best to identify a De Rippe work in the wild, it would be O’Dette; as one of the most influential, technically precise, and emotionally expressive performers in the lute world, he is a fine candidate to be De Rippe’s modern-day counterpart. He more than gives the music its due; the technical demands of these works might not be apparent to listeners who don’t themselves play the lute, but their contrapuntal richness and melodic beauty certainly are. Some of De Rippe’s works have been previously recorded, by O’Dette and others, but this is the first album dedicated solely to this composer in some time. (Hopkinson Smith’s recording, in comparison, was released in 1978.)

To many listeners, then, these works are likely to be unfamiliar. The album is beautifully constructed to that end, as the fantasias on new themes are interspersed among pavanes and galliards on familiar bass lines, or intabulations of better-known vocal works. For me, these in particular permit the listener to hear what De Rippe is doing; listen, for example, to the ways he fleshes out the vocal texture through ornamental passages in “Martin menoit,” or by doubling a moving line at the octave, or breaking up chordal passages and building in greater numbers of voices in “Douce memoire” or “O passi sparsi.”

O’Dette is at his expressive finest throughout the album, but the concluding guitar fantasias (“Fantasie II de Guyterne” and “La Seraphine”) are standouts, and the close acoustic space allows him to really bring out the dynamic contrasts in “L’Eccho.” It’s a lovely, and lovingly created, recording, certain to elevate De Rippe’s reputation as a master of his craft.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.