by Kyle MacMillan

Published October 5, 2020

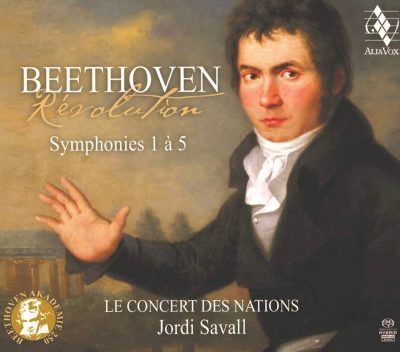

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 1-5; Le Concert des Nations; Jordi Savall, conductor. Alia Vox AVSA9937.

While some of Jordi Savall’s dozens of albums are devoted to familiar names like J.S. Bach or Claudio Monteverdi, much of the Catalan conductor and viol player’s fame has come from his rediscoveries of little-known composers such as Jean-Féry Rebel or José Marín. Most of his attention has been focused on the Baroque era and earlier, but in recent years he has expanded as well into the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

After releasing a compact disc of Mozart’s last three symphonies in 2019, his latest project on the AliaVox label, Beethoven – Revolution: Symphonies 1 to 5, moves into the heart of the so-called standard repertoire and showcases some of the best-known and most frequently performed works by modern orchestras. Working with Le Concert des Nations, a period-instrument orchestra he founded in 1989, Savall is hardly uncovering anything forgotten here, but he clearly believes he is nonetheless rediscovering these works in some sense by performing them in a historically informed manner.

After releasing a compact disc of Mozart’s last three symphonies in 2019, his latest project on the AliaVox label, Beethoven – Revolution: Symphonies 1 to 5, moves into the heart of the so-called standard repertoire and showcases some of the best-known and most frequently performed works by modern orchestras. Working with Le Concert des Nations, a period-instrument orchestra he founded in 1989, Savall is hardly uncovering anything forgotten here, but he clearly believes he is nonetheless rediscovering these works in some sense by performing them in a historically informed manner.

“Our principal aim of projecting in our 21st century the full richness and beauty of these well-known symphonies — all too often presented in an oversized, over-elaborate form — is to restore to these works their essential energy through a proper natural balance between the colors and the quality of the orchestra’s natural sound,” Savall writes in his accompanying notes.

And he succeeds in that mission handsomely, with each of these interpretations imbued with well-defined proportion and clarity. There is a litheness and transparency to the sound, with carefully delineated solos set against a rich sense of the whole. The playing is vibrant and vivacious.

The gold standard for period-instrument recordings of the Beethoven symphonies was set in 1994 with the release of the complete set of period-instrument recordings of the nine symphonies by conductor John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. If this first installment in what Savall hopes will be a complete look at the symphonies does not topple Gardiner and his forces from that preeminence, it certainly challenges that standing and, at the very least, gives listeners a very worthy alternative take.

Savall was a pioneer alongside such leaders as Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Christopher Hogwood, and Trevor Pinnock in launching the period-instrument movement, which gained momentum in the 1970s. While at first they sought to revive and reassess the music of the Baroque era and before, some of them and subsequent adherents have pushed ever later into history, bringing a historically informed approach to music of the 19th century and even parts of the 20th century.

The box set of Sir Roger Norrington’s groundbreaking period-instrument recordings of the Beethoven symphonies with the London Classical Players was released in 1989, so there is nothing especially revolutionary about what Savall is doing here. In his notes, he writes that for this recording, he used 55-60 musicians depending on the symphony, a number closer to that used by Beethoven for the first performance of his symphonies and smaller than often employed by modern orchestras. That musical deployment is comparable to the forces — 66 musicians, including the extras necessary for the Ninth Symphony — that Gardiner brought to the U.S. last year for the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique’s performances of all nine symphonies.

Thirty-five of the recording’s musicians were drawn from Le Concert des Nations, and the rest were 20 young instrumentalists from around the world chosen via in-person auditions. The performances were prepared through intensive sessions, or what Savall describes as “academies” that took place in the spring and fall of 2019. Judging by the resulting recording, this approach appears to have worked. The veteran players and newcomers mesh well, and the playing is at a high level overall.

One of the trickiest aspects of the Beethoven symphonies are the composer’s metronome markings, which many performers over the years have found unworkable or not artistically sound. Part of the historically informed approach to the composer has meant returning to those controversial tempos, something both Harnoncourt (with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, mostly on modern instruments) and Gardiner did, though the latter was more willing to deviate when it made sense to him to do so. Savall indicates that he has respected tempos with only a “few rare exceptions.” And, indeed, when looking at the timings of the movements on this album, they are largely in line with those of Harnoncourt and Gardiner.

In examining Savall’s Beethoven album, it makes sense to compare and contrast his take with those of Harnoncourt and Gardiner. To do that, here is examination of three movements from the first five symphonies with accompanying timings for each:

- Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36, Movement II, Larghetto. Savall: 10:28. Gardiner: 10:19. Harnoncourt: 10:30. Savall’s take has a winningly easy-going, genial feel with airy, natural-seeming phrasing, adroitly handled dynamic contrasts, and eloquent woodwind solos. Much the same could be said about Gardiner’s relaxed version, which is similarly appealing, but Harnoncourt’s reading doesn’t have the same level of interpretative subtlety as the other two.

- Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 (“Eroica”), Movement I, Allegro con brio. Savall: 15:32. Gardiner: 15:34. Harnoncourt: 15:53. Savall brings a compelling urgency to this movement, with crisp articulations and snappy sforzandos, and smartly balances the thrust of the big outbursts with the intimacy of the softer moments. There is much to praise about Gardiner, who manages a more easy-going touch overall without sacrificing punch when needed. Harnoncourt offers a more full-bodied sound, but his version drags at times and comes off as more inert.

- Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, Movement IV, Allegro. Savall: 11:03. Gardiner: 9:50. Harnoncourt: 10:51. Although Savall imposes a surprising sense of restraint or containment, he builds the drama incrementally and organically and ultimately generates the required feeling of grandeur and power. Harnoncourt’s take has a bigger feel, with more sweep and a handsome brass sound, but, again, there is a sense of the momentum lagging. Gardiner’s interpretation is unquestionably faster and more muscular, and it is thrilling in its way.

Savall had intended to prepare and record the remaining four symphonies this year, but those plans had to be discarded because of the coronavirus pandemic. When or if it the project will be completed remains up in the air.

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.