by Karen Cook

Published February 3, 2020

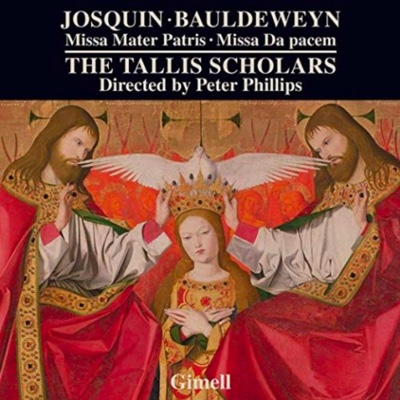

Josquin: Missa Mater Patris / Bauldeweyn: Missa Da pacem. The Tallis Scholars (Peter Phillips, director). Gimell CDGIM052

The readership of Early Music America likely needs no introduction to either the Tallis Scholars or to Josquin. Noel Bauldeweyn, on the other hand, might not be quite so much a household name. Moreover, how is it that Bauldeweyn (c. 1480 – c. 1513) even appears on this new recording, the eighth of nine albums in a series of the complete Josquin Masses? As scholars, and the Scholars, point out, both of the Masses included here have been faced with doubt and scrutiny with regard to a secure attribution to Josquin. The Missa Mater Patris is, in numerous ways, quite different from the style shown in known Josquin works. As opposed to earlier pieces, this Mass is less dense, a bit airier and more open in places, makes use of different kinds of harmonies, and, perhaps most significantly, is the only Mass in which Josquin quotes a contemporary, namely Antoine Brumel.

For this reason, some have speculated that this work might have been written in homage to Brumel upon his death, presumed until recently to have occurred 1512–13 (and on this note, I might suggest readers revisit my EMA review of Musica Secreta’s premiere recording of Brumel’s complete Lamentations, which asks whether Brumel might have lived considerably past such a date). However, the Mass also features some canonic duets and other kinds of borrowing that do seem Josquin-like, which have caused some to treat it as an authentic work. The Missa Da pacem, by contrast, is attributed in one source to Josquin and in another to Bauldeweyn, but since the 1970s the ball has come down more or less squarely in Bauldeweyn’s court. Bauldeweyn, incidentally, was a much younger contemporary of Josquin’s who was active in the Netherlands in the early 16th century; his works were copied widely across Western Europe.

For this reason, some have speculated that this work might have been written in homage to Brumel upon his death, presumed until recently to have occurred 1512–13 (and on this note, I might suggest readers revisit my EMA review of Musica Secreta’s premiere recording of Brumel’s complete Lamentations, which asks whether Brumel might have lived considerably past such a date). However, the Mass also features some canonic duets and other kinds of borrowing that do seem Josquin-like, which have caused some to treat it as an authentic work. The Missa Da pacem, by contrast, is attributed in one source to Josquin and in another to Bauldeweyn, but since the 1970s the ball has come down more or less squarely in Bauldeweyn’s court. Bauldeweyn, incidentally, was a much younger contemporary of Josquin’s who was active in the Netherlands in the early 16th century; his works were copied widely across Western Europe.

Issues of attribution aside, both Masses are performed here in top fashion, as are the Brumel motet and the Da pacem chant on which they are based. The Scholars hit that sweet spot between forceful and tender, the trim forces allowing for a transparency that nicely highlights the borrowed material and the interesting counterpoint. The opening Kyrie of the Bauldeweyn, for example, is vigorous and compelling, and the layered duets in his “Pleni sunt caeli” draw the listener’s ear through the work with beautiful momentum. The Scholars have a lovely blend in the more homophonic sections, as well; listen to Josquin’s Crucifixus, for example, where the bass motion set apart from the other higher voices is particularly noteworthy. Certain sections, like the sparse Benedictus in Josquin’s Mass, are treated a bit more reverentially, but not without control and a sense of careful shaping.

In the liner notes, Tallis Scholars founder and director Peter Phillips expresses a hope that this recording is a champion for the Bauldeweyn Mass, and I believe it succeeds in spades. It’s a compelling recording of two compelling Masses, and it continues to reward with each listen. I await their ninth and final recording of the complete Josquin Masses with excitement, and hope they might also find it worthwhile to return to Bauldeweyn.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.