by

Published February 25, 2019

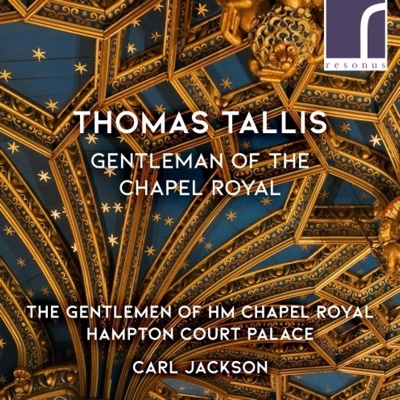

Thomas Tallis, Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal

The Gentlemen of HM Chapel Royal, Hampton Court Palace

Carl Jackson, conductor

Resonus RES10229

By Benjamin Dunham

The urge to experience art in appropriate settings is certainly not unusual among the readers of this website. We may play ancient instruments in a way we hope is historical. We study old paintings for iconographic support. We visit architectural spaces that survive from earlier ages.

In our enthusiasm, we try to make ourselves aware of the compromises needed to bridge the then and the now. But what allowances are needed to listen to masses and motets by Thomas Tallis when they are sung by a choir that could be drawn from the musical retinue of Henry VIII, one that records in the chapel of Hampton Court Palace, where it may be imagined some of these works were performed?

In our enthusiasm, we try to make ourselves aware of the compromises needed to bridge the then and the now. But what allowances are needed to listen to masses and motets by Thomas Tallis when they are sung by a choir that could be drawn from the musical retinue of Henry VIII, one that records in the chapel of Hampton Court Palace, where it may be imagined some of these works were performed?

We are there, back then, in the right acoustic and with the right forces at hand. Alone, this might provide a thrill for the average early-music aficionado. But beyond this is the beautiful music itself, all of it for various reasons written for a choir of men’s voices, without a higher treble part sung by boys. Thomas Tallis became a member — singer, organist, composer — of the Chapel Royal in the early 1540s, a few years before the end of Henry’s reign. Before Tallis died in 1585, his service had extended through the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, a term remarkable for both political survival and artistic achievement.

Two of the works, the Mass for Four Voices and In pace in idipsum, were written at the time of Henry VIII in four clear parts and performed by eight singers. The Missa Puer natus est nobis and motets Suscipe quaeso Domine, prima pars (and Si enim iniquitates, secunda pars), Miserere nostri Domine, and Loquebantur variis linguis are later works written for seven voices and are performed by 14 singers.

Whether in reduced or expanded form, the texture of the vocal ensemble, under the direction of London-born Carl Jackson, sounds ideal. Were the ghosts of earlier Chapel Royal musicians guiding the singers to achieve exactly the right resonance as they snaked their way though intricate part-writing, delicious cross-relationships, and rock-solid cadences?

One work stands out as an example of Tallis’ art as well as his method of inspiration. How to conclude a collection of works published in the 17th year of Elizabeth’s reign (in thanks for her granting Tallis and William Byrd a patent for printing part-music)? The Miserere notri Domine is his 17th piece in the collection (Byrd also wrote 17), and one of its bass parts is just 17 notes. That’s only the beginning of the games Tallis played, including a canon at the unison, metrical augmentation, parts in retrograde, and pitch inversion. The effect is a totally seamless thicket (“tallis”) of mellifluous magic.

As a boy, Benjamin Dunham, former editor of Early Music America magazine, sang as a chorister under Edgar Hilliar at St. Mark’s Episcopal, Mt. Kisco, NY, and Harold O’Daniels at Christ Church, Binghamton, NY, and later sang in the University Choir at Harvard’s Memorial Church under the direction of John Ferris.