by Aaron Keebaugh

Published January 18, 2021

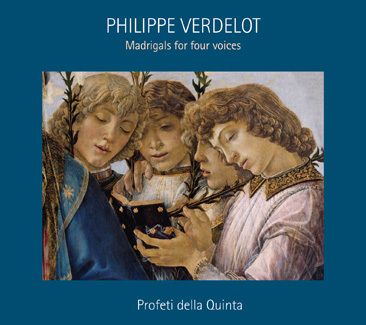

Philippe Verdelot: Madrigals for Four Voices. Profeti della Quinta. Pan Classics PC 10422.

The 16th-century madrigal was as much a literary genre as a musical one. Many of those compositions told of passionate affairs between lovers as an escape from the troubles of daily life.

But to the Israeli ensemble Profeti della Quinta, madrigals could detail pain as well as pleasure. Their new album featuring madrigals by Philippe Verdelot reveals that love is all too often a turbulent road to disaffection.

The disc combines four-part madrigals taken from Verdelot’s first published collection, which was printed posthumously in 1533. Each work is cast in a rich, sonorous style that aptly conveys the passion and ultimate dejection expressed by the texts.

The disc combines four-part madrigals taken from Verdelot’s first published collection, which was printed posthumously in 1533. Each work is cast in a rich, sonorous style that aptly conveys the passion and ultimate dejection expressed by the texts.

The tracks are also arranged in the form of a concept album, exploring emotions ranging from amorous fire to utter depression. By the disc’s end, the narrator has given up on love and, disenchanted, decides to move on with his life.

Led by bass Elam Rotem, the singers of Profeti della Quinta make those feelings palpable through lush and pristine harmonies that make the simplest of Verdelot’s musical textures sound fuller than they appear on paper. But these works are more than mere homophonic treatments of the text. Harmonies glisten with dissonance, and the ensemble’s careful handling of word painting enhances the poignant meaning of each poem.

“Se l’ardor foss ’equale” sounds with a dark resonance befitting the narrator’s suffering over a selfish lover. So does “Se mai provosti donna,” where chromatically shaded harmonies convey the pain of loving an indifferent partner.

“Divini occhi sereni” takes on a somber tone, suggestive of the narrator’s frozen gaze as he is enraptured by his lover’s beauty. The long melismas of “Ognor per voi sosperi” express his fiery passion. He is consumed by desire in “Madonna, qual certezza,” in which the ornate phrases never quite settle into equilibrium. “Madonna, per voi ardo” may seem calm on the surface, but the text relays the mental torture of being lost in love’s enticing dream.

“Gloriar mi poss’io donne,” told from the woman’s perspective, boasts of a lover being faithful, perhaps to a fault. Sung with a supple blend, the ensuing works capture her lover’s tortured emotions. Chromatic shading and textural variations in “Si lieta e grata morte” express his deep yearning for intimacy. “Deh, perchi si veloce,” which unfolds in imitative lines, captures his undying obsession: “The lady is kind, but cruel.”

The singers sensitively convey the narrator’s spiral into despair. In “Con soave parlar con dolce accento,” he awakens heartbroken from a dream and abandons his efforts to try to win over his lady. He sinks into loneliness in “Passer mai solitario in alcun tetto,” in which the singers’ soft passages accompany thoughts of suicide.

Breaking up the overarching narrative of this disc are instrumental versions of selected madrigals, all played with silvery tone and delicate balance by a viol consort made up of Giovanna Baviera, Anna Danilevskaia, Elizabeth Rumsey, and Leonardo Bortolotto.

But those diversions don’t mask the pain of the remaining set. The lady appears, as if in a dream, one final time in “La bella man mi porse Madonna.” It is a fleeting vision, and the singers conclude the madrigal — the final line translates to “O how sweet it is to die” — with sounds of poignant sorrow.

The singers end on a life-affirming note in “Gran dolor di mia vita.” Consumed by bitterness, the narrator decides to continue with his life. Swearing off love may be a firm resolution, but the way forward will be anything but easy.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as Boston critic. He teaches courses in music and history at North Shore Community College in Danvers, MA.