by Aaron Keebaugh

Published June 14, 2021

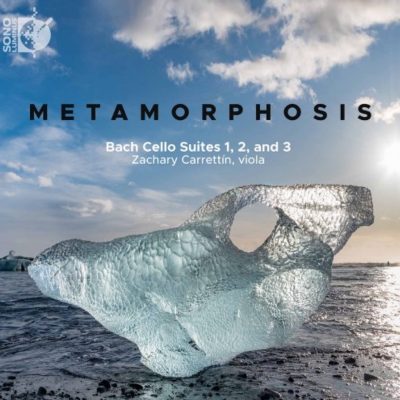

Metamorphosis: Bach Cello Suites 1, 2, and 3. Zachary Carrettín, viola. Sono Luminus DS9224.

Bach’s cello suites mean different things to different performers. Pablo Casals, who played through one of the suites every morning, saw these works less as technical exercises than as a dialogue between dance and lyricism. Yo-Yo Ma, who toured with these pieces in 2019 as part of the “The Bach Project,” recast them as essays in universalism, capable of bridging vast human differences.

To American multi-instrumentalist and conductor Zachary Carrettín, Bach’s cello suites are more personal. His recording of the Suites 1-3, played on viola, reaffirms the idea that Bach’s music can provide solace in the midst of difficult times.

To American multi-instrumentalist and conductor Zachary Carrettín, Bach’s cello suites are more personal. His recording of the Suites 1-3, played on viola, reaffirms the idea that Bach’s music can provide solace in the midst of difficult times.

Carrettín recorded the suites during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which took the lives of several friends and family members. Through grief, he came to see Bach’s music as a vehicle for reflection leading to personal and spiritual transformation.

Performing the suites on instruments other than the cello has historical precedent. Robert Schumann and Leopold Godowski each made rather eccentric transcriptions with piano accompaniment. A more sensitive example is American violist Helen Callus’s 2011 recording of the complete suites that reveals each dance’s stunning, aria-like quality.

Carrettín unveils the soulful melancholy etched within this music. That is most evident in the sarabandes, which take on a gentle vocal arc. The violist’s sensuous rendering of the Sarabande from the Suite No. 1 in G Major suits the dance’s tradition, while his dry tone conveys a sense of desolation. Bach’s writing in the Sarabande from the Suite No. 2 in D Minor recalls the emotional tension of the St. Matthew and St. John Passions, with Carrettín’s double stops adding to the gravity of each line. A similar expressivity also marks Carrettín’s reading of the Sarabande from the Suite No. 3 in C Major.

The preludes unfold with an improvisatory quality, perhaps a nod to the movements’ history as a warm-up for the performer. Carrettín’s generous rubato and lingering tempos endow them with a searching intimacy. He realizes the second suite’s Prelude as a meditation where quick modal shifts tip the music toward darkness. In the third suite’s Prelude, his gentle bowing and silvery tone bring the music back to the light.

The pulse of the Allemandes may not be of prime importance for Carrettín, but these dances nevertheless course with an affecting ebb and flow. The Allemande in the Suite No. 2 even takes on a surprising urgency, with Carrettín highlighting the sudden shifts of tonality. He finds the joy locked within every page of the third suite’s Allemande, tossing off each energetic phrase with ease.

As a whole, the Suite No. 2 is remarkable for its emotional tension. Carrettín’s reading tilts towards the romantic as he explores every shade of the music’s free flow and songful delicacy. In the Courante and Menuets, the violist uses his wide rubato to bring the emotional contrasts into sharp focus. His decision to perform the da capo repeat of the first Menuet in pizzicato brings a refreshing splash of color. Carrettín also varies and colors his tone in the Gigue, highlighting multiple dimensions within the single running line.

The Suite No. 3 supplies the most technical fireworks, and Carrettín unleashes the flourishes and arpeggios with aplomb. The Courante courses vibrantly. Deft fiddling in the Gigue resounds with spring-water clarity.

Surprisingly, the Bourrée movements focus once more on emotional depth. Their lines sing under Carrettín’s fingers, channeling the same tender expressivity found in Bach’s cantatas. Through the pain of loss and the inevitable reflection it brings, this performance counsels that we can see the world anew.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for Corymbus, The Musical Times, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as a regular Boston critic. He teaches courses in music and history at North Shore Community College in Danvers, MA.