by

Published October 8, 2018

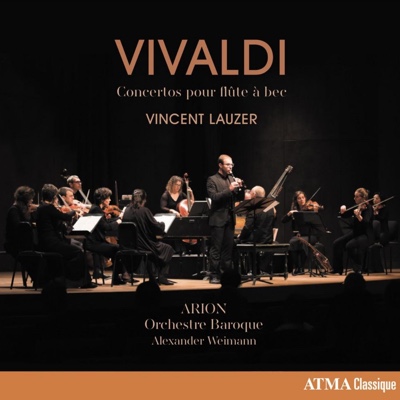

Vivaldi: Concertos Pour Flûte à Bec

Vincent Lauzer, recorder; Arion Baroque Orchestra; Alexander Weimann, conductor

ATMA Classique ACD2 2760

By Andrew J. Sammut

Discs like this one give the lie to the idea that Vivaldi rewrote the same concerto several hundred times (or whatever Stravinsky supposedly said about him). The rich low strings opening up RV 312R’s central movement, the harmonic zig-zags of RV 441’s finale, the downright jarring dissonances of RV 442’s otherwise placid Largo, or the melody skipping over a glassy lake of strings in RV 443’s second movement are far from cookie-cutter devices. Vivaldi’s highly-structured, often virtuosic, and incredibly expansive catalog of works may sometimes blur together, but recorder player Vincent Lauzer and Canada’s Arion Baroque Orchestra illuminate its formal as well as its expressive variety.

Violist Jacques-André Houle’s liner notes explain that Vivaldi composed some of the most difficult works for the recorder of the Baroque era. Lauzer meets these demands with precision and polish throughout the recital, but it is obvious that he reads, hears, and feels through the racing arpeggios and stacked sequences into something deeply personal. From the first track on, he makes a real event out of Vivaldi’s ornate passages with subtle changes of articulation and rhythmic drive. The closing Allegro of RV 445 is a prime example of Lauzer handling even the most labyrinthine lines with care and attention to detail. His metronomic precision actually turns the rapid-fire chirps of RV 312 R’s finale into a riveting account rather than a mechanical exercise.

Violist Jacques-André Houle’s liner notes explain that Vivaldi composed some of the most difficult works for the recorder of the Baroque era. Lauzer meets these demands with precision and polish throughout the recital, but it is obvious that he reads, hears, and feels through the racing arpeggios and stacked sequences into something deeply personal. From the first track on, he makes a real event out of Vivaldi’s ornate passages with subtle changes of articulation and rhythmic drive. The closing Allegro of RV 445 is a prime example of Lauzer handling even the most labyrinthine lines with care and attention to detail. His metronomic precision actually turns the rapid-fire chirps of RV 312 R’s finale into a riveting account rather than a mechanical exercise.

Lauzer’s tone on alto, soprano, and sopranino recorders is centered, full-bodied, and often beautifully vibrato-less. The contrast between Lauzer’s big, round sound and Arion’s drier strings on the opening Allegro Ma Non Tanto of RV 441 adds further textural as well as narrative interest. RV 441 turns into a miniature scena, recalling the composer’s lengthy theatrical catalog: Opening with divided strings wavering over and under the lead, Lauzer begins his solo in introverted fashion before dramatically opening up into sustained notes and descending runs. The subsequent slow movement finds him working with shadings of tone and dynamics. The final movement pits the orchestra and the soloist against one another in a heated dialog.

Arion also gets to really lock in with Lauzer in RV 312 R, as well as the duel in RV 441. The well-known La Notte concerto (originally composed for transverse flute) finds soloist and orchestra conjuring up some dreamy, haunted evening with creeping rhythms, muted strings, and staccato outbursts. Arion’s halting gestures and extreme dynamics sometimes come close to exaggeration, yet it is hard to fault these musicians’ obvious passion. The “Sonno” (Slumber) section also features some particularly evocative sustained chords. Most of the time, Arion is accompanying Lauzer rather than competing with him, and while the group never draws undue attention to its part, there is impressive musicianship at work underneath the soloist. Vivaldi would drop the continuo and use upper strings as the sole accompaniment on countless slow movements; Arion’s graceful strings chanting behind the soloist illustrate the sheer simplicity and power of this effect.

Vivaldi was often writing his concertos for the orphans of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, for human beings he knew and with whom he no doubt developed personal relationships. The idea of a human printing press churning out repetitive works is not just unhistorical but misses the charm and invention of Vivaldi’s music. Lauzer and Arion provide strong advocacy for the Red Priest in their program selection and especially through these performances.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about early music and traditional jazz for Early Music America, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, All About Jazz, and his own blog. He lives in Cambridge, MA.