by Andrew J. Sammut

Published May 18, 2020

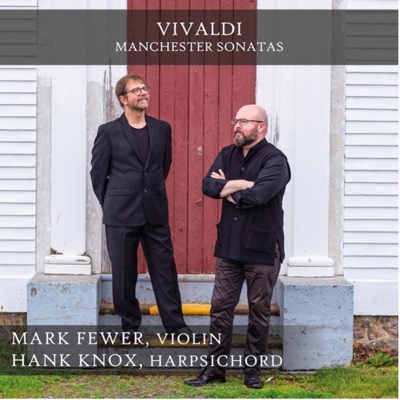

Vivaldi: Manchester Sonatas. Mark Fewer, violin; Hank Knox, harpsichord. Leaf Music LM229

Vivaldi never visited England, but the 12 violin sonatas he offered to Italian patron Cardinal Ottoboni passed through several English owners. The collection was eventually purchased by the Manchester Public Library, where it was discovered by musicologist Michael Talbot in 1973 and received the somewhat misleading nickname of “Manchester violin sonatas.” While just four works were entirely new, the others constituted significant reworkings of earlier sonatas and concertos.

The sonatas remain a musical as well as an academic find. All cast in four movements (with some dance titles inserted later), their structural uniformity hides a wide emotional and technical range, as well as plenty of thematic and harmonic twists. Sonata 2’s Gigue careens through rhyming octaves, extended sequences, and unusual phrase lengths. Tight intervals make Sonata 4’s Andante shake in frustration, while Sonata 6’s Prelude proceeds in refined steps. There’s also plenty of sheer beauty in wordless arias like Sonata 3’s lonesome Largo, Sonata 7’s vulnerable Grave, and the serenade starting Sonata 11.

The sonatas remain a musical as well as an academic find. All cast in four movements (with some dance titles inserted later), their structural uniformity hides a wide emotional and technical range, as well as plenty of thematic and harmonic twists. Sonata 2’s Gigue careens through rhyming octaves, extended sequences, and unusual phrase lengths. Tight intervals make Sonata 4’s Andante shake in frustration, while Sonata 6’s Prelude proceeds in refined steps. There’s also plenty of sheer beauty in wordless arias like Sonata 3’s lonesome Largo, Sonata 7’s vulnerable Grave, and the serenade starting Sonata 11.

Canadian violinist Mark Fewer and harpsichordist Hank Knox seize on all that variety to create a sensitive and exciting recital. Performances are thoughtfully shaped and paced from the opening of the first sonata, which also displays Fewer’s natural way of integrating chordal stops into the melodic fabric. His ornamentation respects Vivaldi’s lyrical gifts and shares his own personality as a soloist. Fewer’s dynamic shading and articulation make repeated phrases like those in Sonata 5’s Saraband into gripping statements. The worrying motif in Sonata 7’s Prelude grows in anxiousness each time it returns.

Fewer displays an interpretive and technical knack for details without sounding fussy, as in Sonata 4’s Corrente — with its frenzied descents and pizzicato exclamation points — or his exploration of the winding little theme in Sonata 8’s Andante. He also spotlights Vivaldi’s imaginative use of dissonance without seeming mannered. Sonata 9’s bevy of suspensions are positioned like intriguing questions.

Vivaldi’s scoring foregoes interaction between soloist and continuo, so Knox is given a strictly accompanimental role. His support is seamless enough to almost take it for granted. Yet Vivaldi composed only an unfigured bass part, so Knox isn’t just realizing a continuo but extemporizing harmonies. His rich voicings and steady beat audibly spur Fewer’s creativity. Subtle tempo fluctuations in Sonata 8’s Prelude exemplify the duo’s unified feel.

The use of just a keyboard without a cello or other chordal instruments further clarifies the musical lines. The violin and the limpid single-manual Italian harpsichord built by Keith Hill (based on a model by Giovanni Battista Giusti kept at the University of Michigan) meld into a uniquely crisp string sonority. Fewer’s slicing strokes and Knox’s flurries make for a resonant match in Sonata 10’s Corrente.

Though these sonatas appear on other recordings, and Baltic Baroque recorded eight of them last year, the last complete sets were released in the ’90s: Andrew Manze’s nuanced but slightly conservative reading and Fabio Biondi’s earnest account. This release adds a highly individual and refreshing addition to the catalogue.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about Baroque music and hot jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, the IAJRC Journal, and his own blog. He also works as a freelance copy editor and writer and lives in Cambridge, MA, with his wife and dog.