by Steven Silverman

Published August 8, 2022

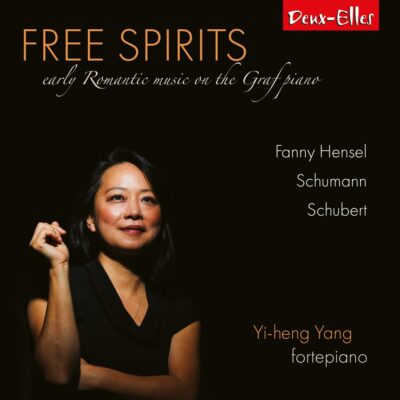

Free Spirits: Early Romantic Music on the Graf Piano. Yi-heng Yang, fortepiano. Deux-Elles DXL 1187

Fortepianist Yi-heng Yang’s new recording of early Romantic works is uniformly excellent and interesting. On the faculty at Juilliard and with several strong discs to her credit, her latest recording includes the familiar, the relatively familiar, and the novel: the great Schubert Sonata in G major D. 894, three of Robert Schumann’s Novelettes op. 21, and four keyboard lieder from Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’s op. 8. It’s available as digital release from the British Deux-Elles label.

Most people will likely know these works from modern piano performances. Yang’s instrument is a preserved Graf fortepiano from 1825. Key differences from the modern piano are leather hammers, strings at less tension, and a wooden frame, where there’s no cast-iron plate to hold strings under higher tension. It also has extra pedals, including a so-called moderator pedal—a strip of felt between the hammers and strings which audibly muffles the sound. A superficial impression is that the instrument is underpowered and a little tinny sounding in its middle register (courtesy of the leather hammers), but the ear adjusts quickly and the instrument’s strengths are apparent: a sweet melodic character (attributable to the performer, as well as to the instrument), easy balances and clarity of textures due to the sound’s more rapid decay, plenty of oomph (at least at the close range of a recording), and ability to execute accents and sforzandi without the notes lingering so long as to spoil the effect of a sudden interjection. In the hands of the gifted Yi-heng Yang, the instrument has all sorts of color and nuance, and is fully capable of virtuostic explosions.

The Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel keyboard lieder are novelties to many of us, well worth hearing. These pieces show an unhackneyed melodic gift, including some deviations from the standard early Romantic-era four-bar phrase length. There’s harmonic adventurousness—the opening piece, in B minor, touches F major at one point—and a flair for chromatic exploitation, both melodic and harmonic. Hensel’s music does not sound like her celebrated brother’s. Surprisingly, however, given the generally high quality of inspiration, each of these four pieces ends disappointingly, as if the composer runs out of ideas and just stops the proceedings with a tonic chord or, sometimes less convincingly, concludes the opening piece with an unwarranted turn to the major and a series of pedestrian chord progressions.

Yang is a great advocate for this music. She lets it all unfold naturally. She delineates melody from accompaniment impeccably—two of the pieces have clunky repeated chord accompaniments, which Yang deftly keeps in the background—and executes rapid figurations with aplomb. She makes clear that we are hearing a composer with an original and compelling voice.

Schubert’s G major Sonata has an unusual emotional trajectory. Unlike the three final Beethoven sonatas, which commence on earth and ascend to spiritual heights, this sonata, written during Beethoven’s lifetime, does the reverse. It opens in the Empyrean, with chords and modulations floating nearly timelessly, an atmosphere which is sustained throughout the extended first movement. Even the explosions in the development section magically dissolve into something gently celestial—the instrument’s rapid decay allowing this effect to register easily and tellingly. The succeeding movements gradually descend from these heights to an earth-bound, pastoral finale, which, in its final few measures, conveys the mood of the sonata’s opening, suggesting that instead of going from A to B, the music has come full circle. Heaven and earth are not necessarily so far apart.

Yang’s performance captures a lot of this spiritual journey. Her opening has the proper floating timelessness. The second theme is dancelike while retaining a seraphic character. She varies tempo with appealing and unobtrusive flexibility throughout the movement, with certain passages surging ahead, such as the big chordal buildups in the development, but slowing as the music calms. Somewhat less successful are an overuse of unnotated rolled chords, even in the main theme in its return at the exposition repeat. Use of the moderator pedal to provide a distinctly different color for much of the exposition repeat, however, differentiates nicely.

Yang’s middle movements of the sonata are also properly dancelike, not just the Menuetto (obviously a dance) but the Andante second movement as well, which she plays a little quicker than one normally hears, capturing a ländler character often missed. Like the first movement, her readings are full of coloristic nuance, both melodic and harmonic. She pays scrupulous attention to detail, expressive rubato—including the occasional separation of right and left hands at melodic high points—and flexible pacing. Especially effective are the gorgeous trio of the Menuetto with an audible distinction between pp and ppp, and the inner episodes of the second movement, where the explosive chords startle not just due to volume, but to how quickly the sound vanishes.

Her finale has many of these virtues but seems a little quick. To my ear, this results in a loss of the geniality which I hear as the basic affect of the movement. In addition, the main theme, which we hear many times, contains a series of five reiterated soft chords which sometimes sounded effortful at the faster tempo, especially when the repeated figure is solely in the left hand. Some of the inner episodes also seemed a little driven. Notwithstanding these quibbles about the finale, however, this is a notable reading of a masterpiece.

The Schumann group consists of the first, eighth, and second of the op. 21 Novelettes. The most familiar of these is the initial F major, which Yang plays with robust vigor and impeccable left-hand octaves. She captures the requisite poetry in its contrasting sections, including a lovely delay of the climactic melody note as Schumann repeats his yearning in a remote key. The eighth Novelette is a problematic piece, episodic nearly to the point of structural incoherence. Yang makes a good case for it here. The opening is properly turbulent, with the canonic writing well delineated. She poignantly captures Schumann’s direction to play a melody quoted from a Clara Wieck piece—from before they were married—to sound “as if from a distance.” The second Novelette is a perpetual motion showpiece with a lyric middle episode. Yang gives it a bravura account.

Overall, Yang makes a strong case for the music and, not least, for use of the Graf fortepiano in this repertoire. Highly recommended.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 23nd season, and for many years a resident chamber ensemble at Washington D.C.’s Phillips Collection.

More CD Reviews: