by Ellen Sauer Tanyeri

Published December 6, 2024

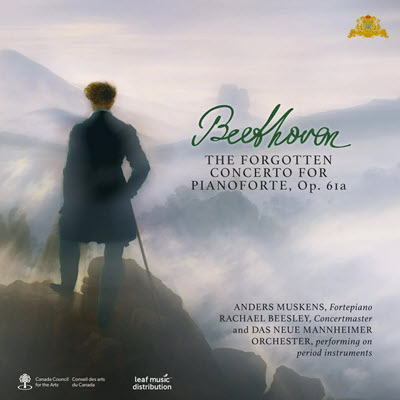

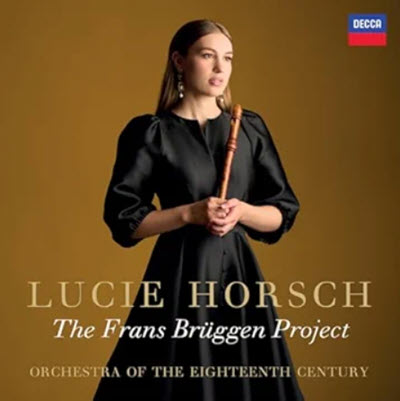

The Frans Brüggen Project, Lucie Horsch, recorders, with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century. Decca Classics B0D82G7LKP

Brüggen’s artistic mission: by adding the ‘limiting’ factor of historical instruments and sensibilities, a player could open up unlimited and essential possibilities of expression

Recorder virtuoso Lucie Horsch’s The Frans Brüggen Project is a brilliant homage to the early-music pioneer, celebrating what would have been his 90th birthday. This expansive album is a collaboration between Horsch, the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century, which Brüggen co-founded in 1981, and his widow, Machtelt Brüggen Israëls, who oversaw Horsch’s use of her late husband’s instruments.

It’s a conversation across centuries — between long-dead composers, all-but-forgotten instrument builders, and contemporary performers. It’s a conversation between generations — a historical performance visionary and one of today’s brightest young stars. Sometimes this dialogue is breath-taking in its immediacy, and other times in its poignant juxtapositions: Horsch performs preludes by Jacques-Martin Hotteterre on a fragile instrument built in the Hotteterre workshop and also Brüggen’s arrangement of J.S. Bach’s Keyboard Concerto in E Major on a fourth flute (a soprano recorder pitched in B flat, a fourth higher than a standard alto treble in F) built especially for him.

Since her break-out success at age 9, Lucie Horsch, born in Amsterdam, has built a rich performing career, driven by a seemingly insatiable thirst for expression and collaboration. In 2016, at 17, she recorded her debut, Vivaldi, and cut a second CD three years later. Her third solo album, the folk-inspired Origins, from 2022, perhaps counterintuitively featured virtuosic arrangements of music distant from the recorder’s own European Renaissance and Baroque roots.

As with Horsch’s previous releases, The Brüggen Project has been an instant hit. Within its first two weeks on the market, Decca sold out of physical copies of the CD. It is worth seeking out a hard copy if only for the program booklet, which features beautiful photographs and descriptions of each of the 17 historical recorders from Brüggen’s collection. Brüggen’s fourth flute, which Horsch plays on the Bach transcription and that she cradles on the cover, is the only modern replica we hear. The other instruments are precious historical originals made of various delicate materials, from wood to ivory to tortoise shell. Because of their age and relative fragility, Horsch was only allowed to handle the instruments for minutes at a time, and her expressive tools for performance were thus markedly different.

Listeners familiar with Horsch’s previous work will be struck by the austerity of the interpretations compared with her usually pyrotechnic ornaments and gestures. In one sense, this decision allows the instruments and their legacy to shine through. It’s easy to imagine each instrument speaking with the same voice it had centuries ago.

In another, more pressing sense, Horsch’s unadorned performances were a practical decision: Because of the limited time each instrument could be played, first takes were often final cuts. Horsch describes the unique pitch and fingering demands of each instrument: “I wasn’t able to explore all their qualities before the recording, so it was a case of being very intuitive and attentive in the moment during the sessions. It needs all your technique and more — I had to do things that my teacher would have said are not done but which the instrument required!”

To prepare, Horsch felt out the instruments, selecting short movements and pieces to highlight their strengths based on each recorder’s idiosyncratic tuning and range concerns. The result is a whirlwind of styles and characters — van Eyck, Corelli, Couperin, Haydn, and beyond — united by performer and intention, but seemingly little else. Indeed, the album asks us to abandon for a moment notions of hegemonic programming that favors whole works and complete sets, returning instead to earlier aesthetic principles of affect — in this case tempered not by key or occasion, but by instrument. It is not through improvisation or embellishment, then, but programming that Horsch’s unique artistic spark pervades this album. (The arrangement of the Bach concerto is the only full piece on the album and the one in which Horsch’s own expressive voice is most audible in the flexibility of the instrument.)

Part of Brüggen’s artistic mission was to show that, by adding the ostensibly limiting factor of historical instruments and sensibilities, a player could open up unlimited and essential possibilities of expression. Pushing audiences and musicians out of their comfort zones, he played a key role in bringing this once-fringe approach to performing into the mainstream, laying the groundwork for performers like Horsch to take the art to new heights. With The Frans Brüggen Project, Horsch and the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century approach the impossible: each brief track opening a tangible and tantalizing window into the past.

Ellen Sauer Tanyeri is a historical flute and recorder player. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Michigan and the Juilliard School and is currently pursuing a PhD in musicology at Case Western Reserve University. She is the 2024–25 Cleveland Orchestra Archives fellow.