(Photo by D. Todd Moore)

By Christine Kyprianides

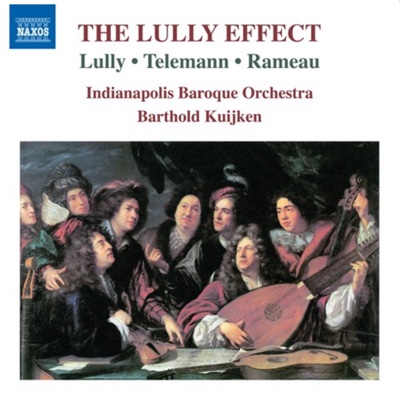

Together with his brothers Wieland and Sigiswald, Barthold Kuijken has been in the vanguard of the early-music movement since the 1970s, performing, teaching, and recording around the world. For the past ten years, he has been the artistic director of the Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra (IBO), which is in the midst of a four-CD project with Naxos Records. The Lully Effect was a highlighted release in September 2018, while The Versailles Revolution will be out in November.

Kuijken spoke recently with IBO cellist Christine Kyprianides.

Kyprianides I remember seeing your parents regularly at concerts in Belgium. Was your family particularly musical?

Kuijken My parents were music lovers, but not musicians. My mother played a little piano, as most girls did in the 1920s. In my father’s family there was a violinist who studied at the Brussels Conservatory and later became a violist. In my mother’s family there were several amateur wind players who played in local wind bands. But that was all.

Kyprianides What led you to become a musician?

Kuijken My older brothers Wieland and Sigiswald were very serious about music, so as a child I always heard somebody practicing at home. Then I got a recorder as a birthday present and started playing it, learning to read music at the same time. It was as natural as riding a bicycle. Later, I studied flute at the music school in Bruges.

At the age of 18, finishing high school, I considered the possibility of becoming a musician. However, because I already had two brothers in the profession, it seemed too easy to just follow their lead. One option was to go to university and study classical philology — Latin and Ancient Greek, which was my other passion. But that would probably mean becoming a high-school teacher. I saw myself as the poor guy sitting in a classroom of students where only one in ten was interested and thought, “Do I really want that for the rest of my life?”

Instead, I studied general art history at university at the same time I was studying at the Brussels Conservatory. It was difficult, but I’m very glad I did it. I learned a lot about how one can think about art. After two years at university, I had to choose either painting, tapestry, or music — some specific branch of art — to continue. Having finished my modern flute studies in Brussels, I was offered a scholarship to study in Holland, focusing entirely on modern music, and I took that opportunity. The training I’d had at the Conservatory in Belgium was very conservative, as the name implies: everything earlier than Mozart was considered primitive, and everything later than Strauss, or even Mahler, was non-music. Webern, Berg, Schoenberg — forget it. The Russians — Prokofiev, Shostakovich — were okay, but the moment it became a little complicated theoretically, or experimental, it was out. In Holland, I was experimenting left and right of the mainstream. More precisely, early music on one side and avant-garde on the other. Wieland and Sigiswald were also playing both modern and early music; it was something that seemed necessary at the time.

Kyprianides That was also my path. What happened to your interest in modern music?

Kuijken I eventually got bored with it because there were not enough good pieces. Now, if I had lived at the time of Telemann, and playing not only Telemann but all his contemporaries, I might have been bored by the bad quality of some of them as well. Today you take the music of Telemann and say, “He’s not Bach or Handel,” but in fact he’s still in the tip of the iceberg. And if you had played the bottom of the iceberg all your life, you might feel just as uninterested. Soon I left that world, occasionally playing modern flute for Debussy or in master classes, but early music became my focus.

Kyprianides How did you begin conducting?

Kuijken In 1996, a wind octet with some added musicians was giving a concert in Belgium with Mozart’s Gran Partita on the program. The first oboe was afraid it wouldn’t work without a conductor, and about two weeks before the performance asked if I was willing to step in. I said yes, got the scores, and studied the pieces. It went very well, we recorded it, and that was the beginning. Then other concerts to conduct came up at the Conservatory, which was good training for me. I’ve also worked with a lot of singers — Bach cantatas and those sorts of works. In 2002, Barbara Kallaur invited me to come to Indiana and conduct a project with the Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra. And this has grown into the wonderful collaboration we have now.

Kyprianides What do you say to the idea that period orchestras should be conductor-less?

Kuijken I think it’s true for many pieces that a conductor should be superfluous. But in preparing concerts and certainly recordings, you save a lot of time if there is a conductor. You avoid having too many cooks in the kitchen. The precision you want for a recording is more difficult to get without a conductor. But I can also speak from my experience playing in the orchestra. I remember playing and recording several Haydn symphonies with La Petite Bande. Sigiswald was playing in some and conducting others, and I greatly preferred when he played over when he conducted. However, the recording went faster when he was conducting.

Some performances can be much better when there is no conductor. But if you are leading rehearsals, the players might ask how you would play this passage, what your ideas are, etc. It’s difficult to stand aside, and you end up coaching rather than conducting, which is too much of one thing and not enough of the other. In that case, I would rather conduct.

Kyprianides You take a radical approach to ornamentation in our recordings. How did you arrive at this?

Kuijken I have always read and re-read early treatises, more than most people. Too often I saw that the music on the page and what I read about it in books from the same period didn’t match. And even less, the music I heard in my ears, what I heard from colleagues in orchestras and what I read, didn’t seem to match either. That conflict was the origin of my book, The Notation is Not the Music [Indiana University Press], which says that notation is a very sketchy thing, only a road map: you can have the map of a city without knowing anything of the city itself.

I became unhappy with the way Lully was performed, for example. While his vocal music was fine, I disliked his instrumental music. Again, whatever I had read about it, what I heard and saw on the page didn’t match. So I started to study the field intensively and did some experimentation with the sources. I began with [Georg] Muffat, of course. I knew a few orchestras that applied Muffat’s bowings, but only the easier and less fundamental ones. I knew not one orchestra that applied his rules of ornamentation. Muffat gives 15 or more ornaments and says they are the most important, but in his printed music you find only the occasional trill, as with Lully. But it’s obvious from his writings that all the ornaments were intended to be played. The question was, where to put them.

Fortunately, the famous Chaconne Passacaille from Lully’s opera Armide exists in an arrangement for harpsichord by [Jean-Henri] d’Anglebert, a contemporary of Lully. I first studied Muffat to become fluent in his style, then added ornaments the way it might have been in that Chaconne. My colleagues told me d’Anglebert’s version was too full of ornaments, but harpsichordists always play too many ornaments. Increasingly, I felt that d’Anglebert just played what he always heard, not adding anything more. And that matched very well with what Muffat said. When I compared the two versions, what I wrote as extra ornaments and what d’Anglebert had written were virtually the same. D’Anglebert had placed fewer ornaments in the middle voices because of fingering difficulties, but whenever possible, if he had a free finger, he had added an ornament. That convinced me this was the right way.

Fortunately, the famous Chaconne Passacaille from Lully’s opera Armide exists in an arrangement for harpsichord by [Jean-Henri] d’Anglebert, a contemporary of Lully. I first studied Muffat to become fluent in his style, then added ornaments the way it might have been in that Chaconne. My colleagues told me d’Anglebert’s version was too full of ornaments, but harpsichordists always play too many ornaments. Increasingly, I felt that d’Anglebert just played what he always heard, not adding anything more. And that matched very well with what Muffat said. When I compared the two versions, what I wrote as extra ornaments and what d’Anglebert had written were virtually the same. D’Anglebert had placed fewer ornaments in the middle voices because of fingering difficulties, but whenever possible, if he had a free finger, he had added an ornament. That convinced me this was the right way.

Kyprianides Are you satisfied with the results?

Kuijken I remember the first sight-reading we did with the IBO when everyone said it was impossible. But we were patient, and for our first recording, we played that very Chaconne Passacaille.

I know for some people it’s still too much ornamentation. That’s okay…if for some people it’s too much, it was not enough for me. You see, that same Lully style took Europe by storm. So even in early Telemann or early Bach, I cannot imagine they would have stripped that music of all its ornaments. They just didn’t write them down.

Gambist and baroque cellist Christine Kyprianides has performed with such ensembles as Musica Antiqua Köln, Huelgas Ensemble, Les Adieux, Les Arts Florissants, and Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra. In 2017, she was named a Fulbright Specialist and awarded an honorary doctorate by the Ionian University (Corfu, Greece) for her contributions to the field of early music.