by Emiliano Ricciardi

Published March 14, 2025

Clément Janequin: French Composer at the Dawn of Music Publishing by Rolf Norsen. University of Rochester Press, 2024. 386 pages.

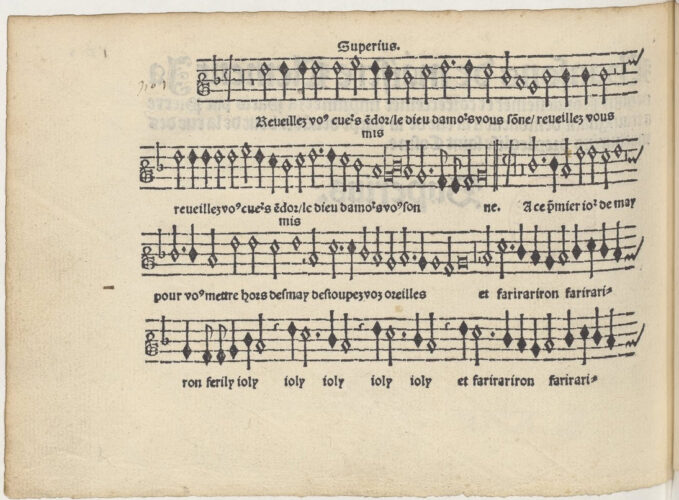

One of the most prominent composers of 16th-century France, Clément Janequin (ca. 1485–1558) occupies a special role in the world of early-music performance, as several of his works, most notably the highly colorful chansons “La Guerre,” “Le Chant des oyseaux,” and “La Chasse,” have long been “hits” among professional and amateur ensembles alike.

Although musicologists have often overlooked lighter genres like the chanson in favor of more elevated ones, several distinguished scholars have engaged extensively with Janequin and the environment in which he operated — notable names include François Lesure, Daniel Heartz, and, more recently, Richard Freedman. Rolf Norsen’s book is a welcome addition to this tradition as the most comprehensive and up-to-date attempt to reconstruct Janequin’s biography and examine his output — not only the chansons, but also his sacred compositions.

Although grounded in scholarly research, the book is accessible and appealing to a broad audience, including performers. In fact, as Norsen declares in the Preface, one of his main goals is to stimulate performers to engage with Janequin’s work: “the absolutely optimal employment of the volume will be one where time after time it is thrust to one side by singers eager to try out yet another of Clément Janequin’s vocal adventures.”

The book’s 10 chapters — some purely biographical, others a mix of biographical and analytical — follow a chronological order, starting with Janequin’s early years (“Beginnings,” Chapter 1) and ending with a discussion of Janequin’s work conditions and highly diverse output in his two final years (“Paris, 1556–58,” Chapter 10). Despite this predictable structure, Norsen’s book is an engaging and rewarding read throughout. For example, the biographical portions are far from tedious lists of events. Rather, they have an investigative tone that captures the reader’s attention.

Especially for the thorniest aspects of Janequin’s biography, such as the uncertainty surrounding his date of birth, Norsen typically presents the reader with various possible hypotheses, evaluates them carefully drawing on an impressive body of existing scholarship, and finally identifies what seems like the most sensible option. Likewise, Norsen provides valuable counterpoint to long-standing narratives on Janequin, such as the notion that his 1549 collection of psalm settings reflected an embrace of evangelicalism. As Norsen argues in Chapter 7 (“Du Chemin and the 28 Psalms of 1549”), these works should be read instead against the growing market for such settings and Janequin’s collaboration with publisher Nicolas Du Chemin, who appears to have launched his music printing activities precisely with this collection.

As indicated by the book’s subtitle (French Composer at the Dawn of Music Publishing), Janequin’s relationship with French publishers — not only Du Chemin, but also Attaingnant from his early years through the 1540s and Le Roy & Ballard in his final years — is one of the central issues addressed in the volume. Norsen should be commended for reconstructing Janequin’s collaboration with each publisher in detail, tackling several important aspects of the music printing business, ranging from patronage and financial matters to book layout and source dissemination.

Given the scope of Janequin’s output, which includes some 200 chansons and several sacred collections (up-to-date catalogues for each category are provided in the volume’s appendices), the analytical sections of the book are inevitably less comprehensive than the biographical sections. For some collections Norsen provides only rapid descriptions of their poetic and musical content, outlining generic features of each. Likewise, questions of performance practice are not addressed as systematically as we might wish: One of the more extended discussions of performance is in the Epilogue, where Norsen advocates for a flexible approach, with possible incorporation of staging elements, to adapt to today’s performance conditions.

Norsen is at his best when he engages in close readings of select works, especially Janequin’s “descriptive chansons,” which he addresses in Chapter 3. For instance, in his discussion of the widely famous “La Guerre” and “Le Chant des oyseaux,” the author argues that there is much more to these songs than the kaleidoscopic sonic effects designed to mimic battle and birdsong. These unusually long works also display sophisticated structures — made of alternating sections labeled by Norsen as “Invitation,” “Explanation,” and “Illustration” — designed to engage with performers’ and listeners’ expectations.

Written in an agile prose, with a tinge of humor where appropriate, Norsen’s book will undoubtedly appeal to a wide audience ranging from scholars to amateur performers. The wealth of information and insight it provides will indeed stimulate its readers to look at Janequin’s music afresh and to savor it through performance. Adding to its value, the book is accompanied by an online companion (https://www.clement-janequin.com/), where readers will find editions of Janequin’s music along with primary sources and bibliographies of scholarly literature.

Emiliano Ricciardi is Associate Professor of Music History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His research area is the late Italian madrigal, with a focus on settings of Torquato Tasso’s poetry. He is the director of the NEH-funded Tasso in Music Project (tassomusic.org).