by Ashley Mulcahy

Published October 6, 2024

Camilla Tassi adds striking visual elements to early-music performances

‘We have to ask ourselves: Who is this performance for? What are we trying to convey?’

If you’re a fan of historical performance, you may not know the name of projection designer Camilla Tassi. But there’s a good chance that you’ve seen her work. Only a few years out of grad school, Tassi has already designed projections for many of the most admired ensembles in early music, from Apollo’s Fire and Boston Baroque to Early Music Vancouver, Haymarket Opera, Les Délices, Oregon Bach Festival, and TENET Vocal Artists, to name a few.

In Tassi’s words, the projection designer’s task is “to provide context with a visual element in a way that supplements, rather than detracts from, the music.”

Often assumed to be a modern development, theatrical projections are, as Tassi explains, nothing new: the technology “originated in Germany in theater in the 1920s. Even before digital projectors, there were glass light projectors,” she says. Wendall Harrington, her MFA mentor at Yale, “has stories from the ’90s about using 40 glass slide projectors with painted slides for the Broadway production of The Who’s Tommy.”

Given the theatrical roots of projection design, opera seems like a natural fit. Indeed, Tassi’s first big gig with a period-instrument ensemble was for Apollo’s Fire’s 2018 touring production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. She designed projections for Boston Baroque’s production of Gluck’s Iphigenie en Tauride in the spring of 2024, and will return to the company for Handel’s Ariodante in April, 2025.

Chase Hopkins, general director of Chicago’s Haymarket Opera, with whom Tassi recently collaborated on a production of Handel’s oratorio La Resurrezione, calls Tassi’s “sensitivity to the repertoire and knowledge of the work invaluable.”

But what about concert performances, which makes up the bulk of the early-music ecosystem? Why incorporate projections into a large-scale work or a program of shorter pieces that were not conceived for the stage?

“I very rarely think a program needs projections, because the music speaks for itself,” says Tassi. “But we do have to ask ourselves: Who is this performance for? What are we trying to convey?”

Take, for example, Giacomo Carissimi’s oratorio Jephte, based on a story from Hebrew Scriptures that has slipped out of common knowledge. An actual oratorio — a small private chapel from which the musical genre takes its name — is a specific environment that elicits a specific atmosphere and posture. Tassi describes a visit to the Oratorio del Santissimo Crocifisso in Rome, where Jephte premiered: “You walk in and you’re surrounded by fresco narratives. As an audience member, you’re affected by that.” (A defining distinction between 17th-century opera and 17th-century oratorio is that the former was meant to be staged and the latter was not.)

‘Even if you replicate the sound as best as possible, you’re missing a whole layer.’

“In concert music we’re very sensitive to the ‘right’ historical acoustic for the music,” Tassi continues, “but we don’t always think about the rest of the experience in the same way. So when you take a work and put it in an auditorium you are changing its context and the experience. Even if you replicate the sound as best as possible, you’re missing a whole layer.” Projection design is one tool that can help address this inevitable gap.

Projections can also maximize opportunities for storytelling, helping an audience latch on to themes or a narrative. Born in Florence, Tassi moved to the U.S. from Italy at age 12. Bilingual in Italian and English, she is acutely aware that unlike the original audience for most Baroque vocal works, American audiences today often come to a work from a different language — not to mention a cultural gap of several hundred years. “Is this piece just for people who speak the language or who have studied this music?” she asks. “I love this music. I want other people to get excited about it and build a relationship with it.”

To create a product that is thoughtful and sensitive, Tassi starts with the music. She’ll delve into the score while listening to a recording and mark it up with initial thoughts and reactions, noting places for possible shifts in the visual content.

Her musical background has proven essential: She grew up taking piano lessons, playing oboe in school band, and singing in choir. As an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame, Tassi earned degrees in computer science and music. As a graduate student, she sang with Yale’s esteemed Schola Cantorum, which performs a great deal of early repertoire and collaborates annually with Julliard415.

After digesting the score, Tassi starts designing. This part of the process begins with conversations about general aesthetics with musical or theatrical leadership. Would they like to incorporate historical imagery? Would they like to include contemporary visual elements? Are there themes in the piece that they would like to emphasize visually?

Tassi explains that most projection designers come from a theater background. As a designer who started in music, her background has uniquely positioned her to design for musical performances: “You have to have a language in common to do this in a way that feels connected,” she says of her collaborations with music ensembles.

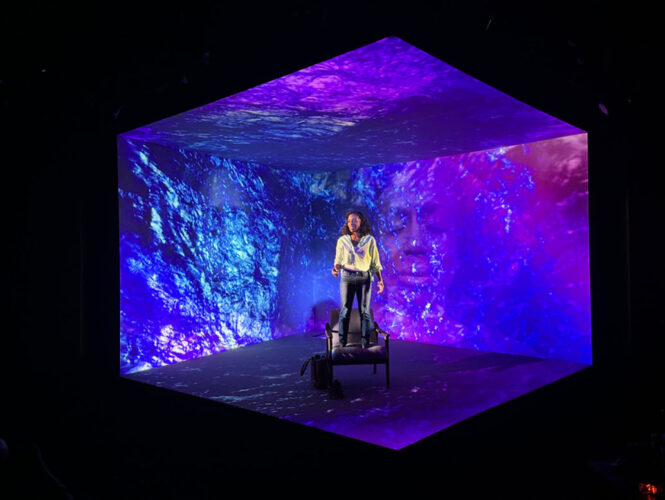

Tassi prefers to tailor her designs to the architecture of the performance venue: “I think a lot about scale and placement of the visual image in relation to the performer. For me it’s most successful when the performer is in the visual world and the projections are encasing the performer instead of having a screen up above and the performer down below. I love to map my designs to the architecture of the space so it almost feels like the music is conjuring the visual.”

This approach has proven to be highly effective. Haymarket’s Hopkins, for example, feels confident that Tassi’s projections, rather than the company’s usual hand-painted scenery designed to “replicate historical scenic conventions,” were the right fit for La Resurrezione. “Modern projection enabled us to envelop the stage in historical paintings that enhanced the musical structure and mirrored the Handelian affect of each aria and character,” he says.

Debra Nagy, artistic director of Cleveland’s Les Délices, echoes this sentiment, referencing a collaboration with Tassi on The White Cat, a pastiche opera on a 17th-century fairytale: “For this production, everyone — singers, puppets, and an onstage chamber ensemble — was part of the action. Camilla’s projections became our world, for both artists and audience,” Nagy recalls.

While acknowledging that a screen might sometimes be the most viable option, Tassi is leery of extending the passive relationships that we all have with screens in so many other contexts into a performance environment. “Projection is not film. It’s theatrical,” she affirms. “I like to call it playing the visual continuo. The queues are always live. I’m pressing queues at specific moments in the music, sitting there with a marked score. This is not a click track. It needs to be just as flexible and breathable and in communication with the music.”

Projections that are ‘flexible and breathable and in communication with the music’

To achieve this degree of flexibility, Tassi attends as many rehearsals as possible, noting that run-throughs, particularly run-throughs in the performance space, are key. There are always tweaks to be made after testing out the projections in the real space in real time, and of course there’s the aspect of acquainting herself with the technologies available in a given space and their limits.

Whether designing projections that, in Tassi’s words, “help bring a work closer to its historical context” or projections that “bring something new to a work that will reflect modern sensibilities,” Tassi sees projection design as a tool that can help us treat a work from centuries past like “a living thing, not a museum piece.”

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle.