by Aruna Kharod

Published November 8, 2024

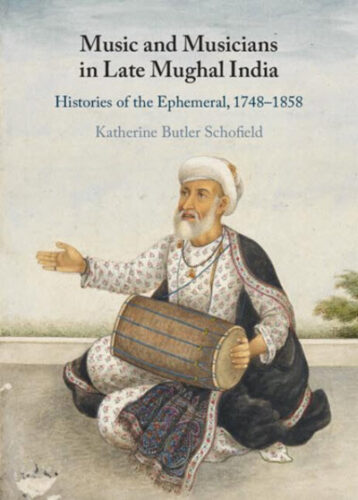

Music and Musicians in Late Mughal India: Histories of the Ephemeral, 1748-1858 by Katherine Butler Schofield. Cambridge University Press, 2023. 343 pages.

Katherine Butler Schofield’s Music and Musicians in Late Mughal India: Histories of the Ephemeral, 1748-1858 presents a nuanced analysis of early Hindustani musical practices in courtly and colonial settings, from Delhi to Hyderabad. The time period examined is one of sociopolitical transition during “the century of the East India Company’s conquest of India.”

Schofield brings together a wide variety of sources, from musical treatises to economic records, primarily in Persian but also in Brajbhasha and Urdu. Presenting multilayered narratives of court musicians and dancers during this timeframe, Schofield examines how performers engaged in ephemeral musical practices — and how music’s fleeting experiences were chronicled, enshrined, revised, and relived by later writers. This multilayered approach demonstrates how Hindustani musical performance is inextricable from political, social, and economic histories of South Asia.

In the introduction, Schofield describes her approach as extending “new scholarship on pre-existing Indian knowledge systems for the first time to the field of music.” She applies the term “paracolonial” to understand how musicians worked alongside and overlapped colonial systems, which were still developing during the era covered in the book. Schofield’s analysis of musicological treatises, historical writings, visual art, and musical notation primarily focuses on musicians and writings that have not previously been examined, making valuable contributions across South Asian studies, cultural history, and musicology/ethnomusicology.

What’s more, her captivating writing style enlivens musicians’ colorful personalities, powerful performances, and lasting effects on historical case studies.

The second chapter traces a court musician’s role as political agent in Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s rise to the throne. Schofield reveals how Khushhal Khan Gunasamudra’s musicking led to a lapse in Emperor Shah Jahan’s courtly administration, indirectly facilitating the victory of his son, Aurangzeb, in a war of succession against his brothers. This account is drawn from a tazkira, a genre of Persian literature memorializing key figures in a discipline through short biographies curated by an author. Tazkiras thus serve as windows into music performance and its potent affective contexts and effects.

Schofield then examines how later musicians used tazkiras and musical genealogies to gain recognition, legitimacy, and courtly employment during a time of political upheaval. Such writings helped displaced musicians establish the credibility of their musical lineages and skills. Specifically, she presents the cases of Delhi kalawant court musicians Anjha Baras and Adarang. By linking the expansion of musicians’ biographies after 1750 with growing tazkira writings on Mughal poets around the same time, Schofield reveals connections between musicological writings and broader literary and cultural milieus.

Chapter 4 explores the interactions of British musicians and composers with Indian performers. Schofield illustrates connections between musical notations made by British music aficionado Sophia Plowden inspired by — and in consultation with — the famous courtesan Khanum Jan. Plowden’s notations were foundational for her male contemporaries, who published adaptations of Hindustani music for musicians in England. This fascinating account shows how two women from very different backgrounds in colonial India collaborated as musicians in their own spheres, linked by a shared passion for performance, and shaping musical interpretation beyond their respective domains.

Schofield’s focus for the next chapter is court musician Khushhal Khan Anup and his courtesan discipline, Mahlaqa Bai, in the early 19th-century Hyderabad court. She dives into one of Anup’s theoretical treatises and collection of songs, revealing Anup’s deep musicological knowledge, compelling writing, and the training of his prized disciple Mahlaqa Bai through examination of the treatise and its illustrations. Schofield counters the enduring stereotype of ustads, or hereditary masters of Hindustani music, as only capable of imparting musical knowledge aurally — or, more bluntly, as “illiterate.” This misconception stems from a previous lack of engagement with musicological texts such as the ones examined in this chapter.

Schofield explores records of the British East India Company as yet another source of musical knowledge and history, which note the presence of dancers and other artists and entertainers as salaried employees in the Company’s ledgers. Conflicts between British salary systems and Indian courtly employ reveal deeper cultural tensions stemming from changing visions of loyalty, economics, and patronage under colonial rule. In this specific case study, the livelihoods, prestige, pedigree, and piety of hereditary artists in Jaipur were intimately tied to the salt stipends that they had received as court musicians as opposed to mere monetary wages. The changing economic milieu of colonial governance heightened tensions between British officers, who now governed the salt flats, and hereditary artists, whose lives and sense of self were tied to the land and its sacred geographies.

The final essay considers how constructions of caste in colonial writings reframed hereditary Hindustani court musicians’ knowledge, communities, and representation. Schofield examines conflicting self-representations of musicians and their portrayals in genres such as the tazkira biographies to ethnographic portraits and writings from British sources. In this case study, the author argues that Anglo-Indian writer James Skinner’s “paracolonial musicological modes” of writing portrayed musicians as “types” rather than as individuals. This marked a shift away from earlier biographical genres such as tazkira. Reinstating the individuality and innovation of Hindustani musicians and theorists, Schofield closes by pointing to Hindustani musicians’ re-theorization of raga and tala systems in the mid-1800s.

Schofield’s significant contributions throughout the book range across South Asian Studies, ethnomusicology, and musicology, illustrating how Indian musicians and musicologists framed and re-conceptualized their musical practices “[predating] European musical interest in this musical world.” In addition, the extensive glossary and genealogies of music that Schofield compiles offer rich resources for those wishing to deepen their understandings of Indian musical-musicological perspectives and legacies.

Aruna Kharod, with a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin, is visiting assistant professor of music at Bowdoin College, where she teaches ethnomusicology and directs the South Asian Performing Arts Ensemble.