by

Published July 13, 2018

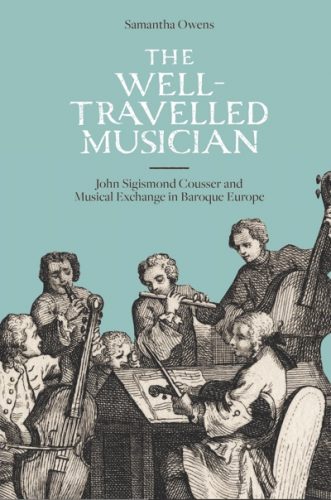

The Well-Travelled Musician: John Sigismond Cousser and Musical Exchange in Baroque Europe. Samantha Owens. The Boydell Press, 2017. 385 pages.

By Mark Kroll

BOOK REVIEW — If Jane Frances de Chantal is considered the patron saint of forgotten peoples, then John Sigismond Cousser must surely be under her protection. Essentially unknown today, Cousser (or Kusser) was held in such high esteem during his lifetime (1660-1727) that Johann Gottfried Walther would write in his Musicalisches Lexicon in 1732, only five years after Cousser’s death, that this “son of a renowned cantor and composer of Pressburg in Hungary…served in various Kapellen as musician and composer, also spent six years in Paris and had the good fortune to be highly favored by the world-famous Lully, and to learn from him the French manner of composition. He travelled all over Germany, and there would hardly have been a place where he was not known.”

We can now add Samantha Owens to the list of Cousser’s protectors and advocates. This wonderful and much-needed monograph not only provides the essential information about Cousser’s life and career, but also allows us to examine the contents of a precious little book, pocket-sized, that Cousser kept and wrote in from the 1690s until his death, but which languished in Yale University’s Beinicke Rare Book and Manuscript Library for far too long. Mostly written in German and English — but also Italian, French, Latin, Dutch, and even Irish Gaelic — Owens rightly claims that this “commonplace book,” as it is called by scholars, “offers a wealth of evidence concerning activities and preoccupations of a Baroque musician, not only professionally, but also far beyond that sphere…offering…numerous seemingly mundane details capable of bringing to life for present-day readers aspects of the day-to-day business of being a musician in the early modern era.”

We can now add Samantha Owens to the list of Cousser’s protectors and advocates. This wonderful and much-needed monograph not only provides the essential information about Cousser’s life and career, but also allows us to examine the contents of a precious little book, pocket-sized, that Cousser kept and wrote in from the 1690s until his death, but which languished in Yale University’s Beinicke Rare Book and Manuscript Library for far too long. Mostly written in German and English — but also Italian, French, Latin, Dutch, and even Irish Gaelic — Owens rightly claims that this “commonplace book,” as it is called by scholars, “offers a wealth of evidence concerning activities and preoccupations of a Baroque musician, not only professionally, but also far beyond that sphere…offering…numerous seemingly mundane details capable of bringing to life for present-day readers aspects of the day-to-day business of being a musician in the early modern era.”

It does indeed. In other words, if you wished you had been a fly on the wall in the Württemberg court, Lully’s Paris, Mattheson’s Hamburg Opera, or Dublin Castle, here is your opportunity. In the book’s eight chapters and five appendixes, you are given rare insights into the era, and into Cousser’s character.

For example, Cousser’s address book contains 500 entries, such as: “Hendel [sic], at MyLord Burlington’s. In London. In Picadilly”; “Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet, veuve de Marin de la Guerre. Organiste de la St. Chapelle, de St. Severin, et de grands Jesuites, dans la Rue Regrattiere. Cel: Musicienne”; plus contact information for Haym, F. Scarlatti, Pepusch, Montéclair, Telemann, Heinichen, and 45 instrumentalists in London. Cousser has also written down musical incipits for the opening movements of 151 instrumental suites composed by Lully, Marais, Campra, De la Barre, Charpentier, Steffani, Rebel, Jacquet de La Guerre, Purcell, Farinelli, Handel, Galliard, and many others.

Some of the information is not related to music, however, but rather to daily life between the last years of the 17th century and the first decades of the 18th. These include remedies for consumption, poor eyesight, gallstones, and “women’s sore breasts,” “an infallible love powder,” and a method to make “a man bold and confident” (Owens implies that this somehow involves the use of the heart of an ape). There are also instructions on the tuning and ranges of various instruments, including theorbo, mandolin, guitar, Spanish guitar, cittern, Italian cittern, gallichon, viola da gamba, psaltery, cornetto, serpent, and spinet, and incipits for 28 keyboard works by composers such as Blow, Kerll, Lebegue, Locke, Orlando, Gibbons, Marchand, and Purcell.

Owens’ book is no less revealing about Cousser’s character. For one thing, he seemed to have had a volcanic temper, as Mattheson described in his Der vollkommene Capellmelster: in “rehearsal, almost all [people] shook and trembled before him, not only in the orchestra, but also those on the stage: at that point he knew how to put forward the mistakes of many people in such a severe manner that often their eyes brimmed with tears. On the other hand, he also calmed down again almost immediately, and sought industriously with exceptional politeness to find an opportunity to bandage the wounds this had caused.”

Cousser also had a sharp tongue outside of the orchestra pit, with a sophisticated and sharp eye towards the business of making music during this era. The quote for which he is best known appears in the section of his book in which he gives advice to foreign musicians trying to forge careers in England. In addition to suggestions about the niceties of dress, dinners, conversation, and the treatment of fellow musicians, he offers this sage and cynical advice to all visitors to the British Isles: “Praise the deceased Purcell to the skies and say there has never been the like of him.”

Equal and genuine praise is due Samantha Owens for offering us this fascinating and excellent addition to our music libraries.

The next releases in Mark Kroll’s recordings of the complete harpsichord works of François Couperin will feature instruments built by Christian Kroll (1775; housed in a château outside of Paris) and Christian Zell (1737; at the Music Instrument Museum of Barcelona). There is no family relation to Christian Kroll, as far as he knows.