by Curtis Price

Published April 19, 2021

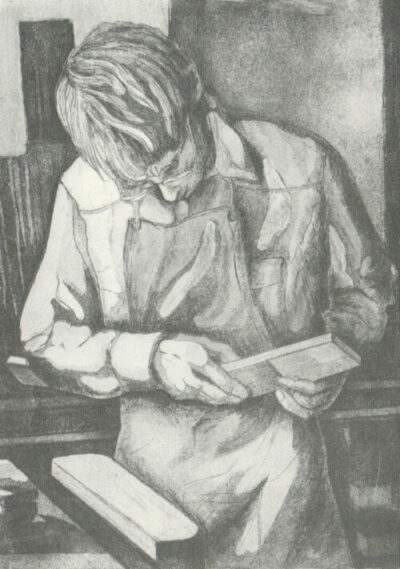

Although active as a luthier for only a short period in the 1970s and ’80s, David Bayer (b. Sept. 11, 1952) built some of the finest Italian harpsichords and classical guitars of the modern era, praised by the greatest players of both. All of his instruments show outstanding craftsmanship and have a superb tone and faultless action. Self-taught and working in relative isolation in St. Louis, he was guided by his ear and blessed with a gift for precision woodworking and engineering second to none.

Harpsichords

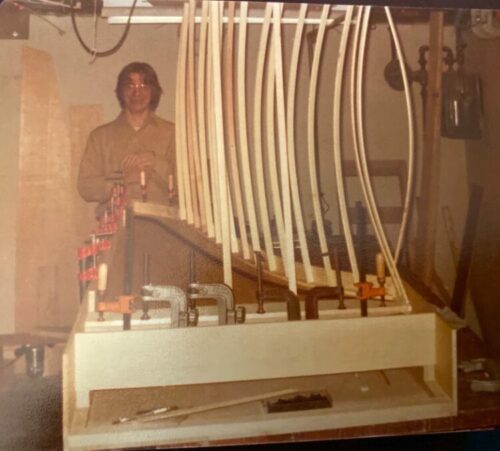

Bayer was a precocious child-mechanic. He made a couple of guitars and even something resembling a clavichord as a young teenager. Although of a rather basic design, his first three harpsichords were based on a 17th-century Italian model, beautifully made, with a remarkable tone and smooth action despite having nylon plectra and jacks attached directly to the backs of the key-levers. (Bayer had unknowingly copied the action of the earliest harpsichords, whose jacks were also let into the key-levers.) With the exception of one German model with characteristic double bent-side and extended range, all that followed were true Italian inner-outers, the instrument itself being enclosed in a protective and decorative box.

Some of these early harpsichords were snapped up by graduate students at Washington University, St. Louis, which was, by happy coincidence, a hotbed of the early-music movement, thanks initially to the residency of Studio der frühen Musik. But there was no suitable harpsichord available in St. Louis at the time, so Bayer was able to supply a strong local demand for keyboard basso continuo.

His instruments grew ever more refined, though Bayer had yet to examine any historic harpsichords and was guided by his instincts for tone and insistence on mechanical perfection. Like the great Cremonese violin makers, he could judge the sound potential of a piece of wood by holding it in his hands; if he thought it was not resonant enough, it would be laid aside — even a nearly-finished soundboard!

Bayer’s fame quickly spread, and in 1977 Albert Fuller invited him to be luthier-in-residence at the Aston Magna Music Festival, for which he also supplied two Italian instruments as the focus was on Monteverdi. He visited the instrument collections at Yale and the Smithsonian, where he took notes and measured various Italian harpsichords. From 1976 onwards, Bayer quilled all of his instruments with crow feathers, and, beginning with No. 11, all were designed to be pitched at A=415Hz. His workmanship was superb; behind-the-scenes was as tidy as front-of-house. It was as if the young Antonio Stradivari had switched to building harpsichords.

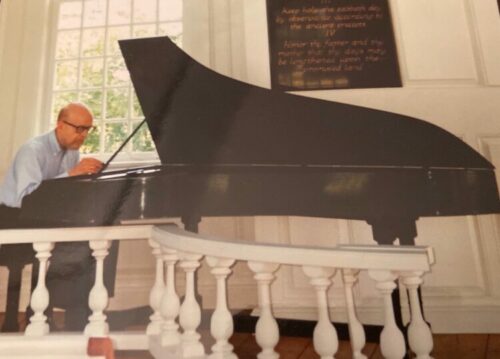

When Trevor Pinnock was artist-in-residence at Washington University in the late 1970s, he had a chance to play a few Bayer instruments, including the remarkable No. 11. This harpsichord is particularly impressive, as one can hear in a YouTube performance below (starting at about 13:00) by its current owner, Charles Metz, who studied with Pinnock during his residency in St. Louis.

No. 11, 1978

As a virtuoso soloist, Pinnock had little use for a single manual Italian but gave Bayer his firm imprimatur. Metz placed an order soon thereafter (No. 14, 1981). Gustav Leonhardt, on tour in St. Louis, also used a Bayer for a concert. His compliments were not effusive, as was his wont, but the great man acknowledged a fine instrument. Nicholas McGegan, another Washington University artist-in-residence, played Bayer instruments for his concerts and enthused about their quality.

No. 15, which I commissioned, is a copy of an instrument dated 1677, illustrated in Frank Hubbard’s Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making, plates I-III, exact in every detail. This would prove to be Bayer’s last keyboard instrument. He made everything from scratch; his hand-forged wrest pins are particularly handsome. With Italian cypress (cupressus sempervirens) unobtainable in the United States at the time, Bayer instead sourced from Canada a beautifully clear flitch of cedar of Lebanon (cedrus libani), which he used for four instruments. In no other respect does No. 15 deviate from the original.

Of course, as with any master, Bayer did not make a slavish copy. Every component was carefully chosen and shaped to take its place in a harmonious whole. Each mitered joint, every inch of ebony inlaid cap molding, every bone touch-place and arcade, every jack, jack tongue and axle is perfect, as beautiful as any original Italian and more accurately made. The instrument remains in pristine condition, the cedar case having turned a golden brown. The walnut and holly jacks float in the box slides, no tongue or spring has ever failed, and no key or rack guide has ever gotten stuck.

Already a believer in crow quill plectra, Bayer invented a tongue mortise punch, the tip ground to a crescent of the same diameter as a tubular crow feather. The mortises hold the quills securely without bending them. The plectra rarely split, and various owners have reported quills lasting for more than 20 years, longer than delrin. If other makers knew of this punch, more harpsichords would today be quilled with feathers.

The tone of Bayer’s late instruments is typically mid-17th-century Italian: a sparkling treble and rich, mellow tenor and bass in a seamless gamut — at once fresh and antique — as can be heard in the Metz performance with No. 11 cited above. The contrast between the stops is pronounced, with the back 8-foot warm and mellow and the front dry and crackling. When the ranks are coupled, the treble becomes brilliant, with the overtones producing a phantom 4-foot stop, a rare phenomenon more characteristic of Flemish than Italian harpsichords.

I came fully to appreciate Bayer’s work when, a couple of years ago, after retiring and with time on my hands, I returned to my youth as an apprentice harpsichord maker. I decided to build a clavicytherium, a vertical version of Bayer’s No. 15. The action with its quadrant jacks was adapted from Martin Kaiser and Matthias Griewisch. The case was made of Italian cypress, seasoned for 40 years. Only after forensic examination of the Bayer, which was always at my elbow, and repeated failure to emulate his methods and standards could I fathom his achievement. For me, and even I suspect for many of the best professional makers today or in the past, he is inimitable. His mature instruments, although based on historical models, have a distinctive style that might at first glance look somewhat naive or pared back but that, I think, is better called “pure”; they are more like cellos or guitars than machines.

After completing this instrument in 1982, Bayer faced a dilemma familiar to many an idealistic, lone luthier. Harpsichords of this quality, based on historic models, hand-planed and using the best materials and never ever sandpaper, take a long time. His almost fanatical devotion to the 17th-century Italian style further reduced his profile in what was then a burgeoning market for two-manual harpsichords, where even small profit margins depended on increasing output, employing assistants, big power tools, shortcuts, and outsourcing. Bayer simply could not countenance any such compromise or expansion of production. Thus began the second phase of his career.

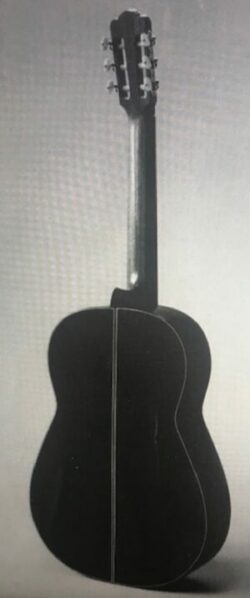

Guitars

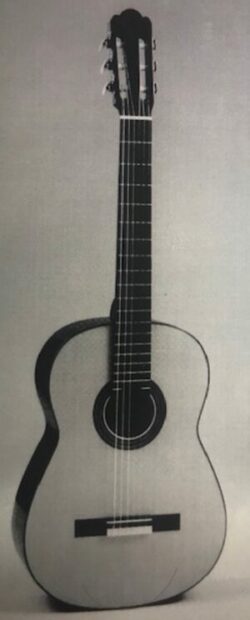

With a fine ear, acute eye, and carving and inlaying skills honed in building his last harpsichords, Bayer decided to make classical guitars based on the “standard” model developed by the great 19th-century luthier Antonio de Torres Jurado. Using only the finest woods and decorative materials, he built “free” on a bending iron without the use of molds, with specially prepared hide glue and luminous French-polishing.

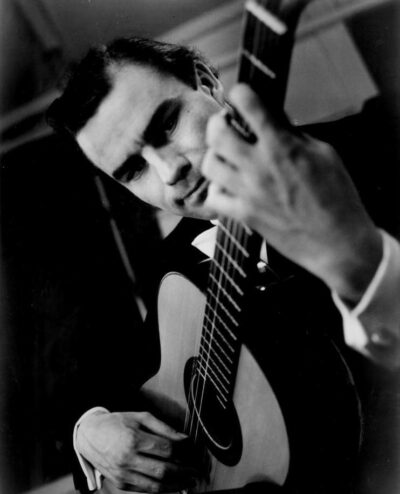

Guitarist Larry Bolles thought Bayer’s first classical instruments “were extraordinary in having singular charm and playability,” considering him already “the best classical guitar builder in the world.” The approbation of a celebrated artist could bring almost immediate international recognition. Members of the St. Louis Classical Guitar Society had gotten wind of Bayer’s instruments and arranged a trial with Julian Bream, one of the greatest guitarists and lutenists of the 20th century. He loved the instrument, declaring it one of the very best he had ever played. Three days later, he placed an order for “a guitar exactly like that one,” paying twice what Bayer was asking. About the same time, Pepe and Celedonio Romero expressed admiration for his instruments, the latter saying “this guitar speaks to me.” A brilliant future lay ahead.

But rotten luck and ill-tempered misunderstanding intervened. The story, however sad — tragic even — needs to be told to understand the trajectory of Bayer’s career. Elated by Bream’s unequivocal endorsement, he got straight to work, determined to make an even better instrument. Professional guitarist John McClellan, a frequent visitor to Bayer’s workshop at the time, recalls reading the lively correspondence between player and maker. Bream wrote eloquently in beautiful 18th-century copperplate, stressing the importance of “a singing E string, and specifically a G string that projected clearly, like an arrow flying through the air, at the same time possessing German-like character and timbre.”

The instrument, which exceeded Bayer’s expectations, was carefully packed up and shipped to England for overnight delivery. Unfortunately, the crate was misplaced and sat on the tarmac at Lambert Airport for a considerable period during one of the hottest summers on record. When Bream eventually received the instrument, it looked perfect and played well, but he thought it was resonating about a semitone lower than what he called a “G-box,” his imagined ideal and, he claimed, the “note” of the guitar he had tried in St. Louis.

Bream immediately ordered a second instrument from Bayer, even sending him six sets of beautiful rosewood from which this guitar and, presumably five more, would be constructed. What neither he nor the maker knew at the time was that the first instrument had been damaged in transit, leading Bream to believe mistakenly that Bayer had over-thinned it.

During his next American tour, Bream made a special trip to St. Louis to have Bayer look at the first instrument and to take delivery of the second. The following account of that fateful meeting is necessarily based on Bayer’s recollection. Bream initially liked the second guitar, with its select rosewood, and over dinner even talked about commissioning a third. But the evening turned sour when Bream said that the resonance note of the new guitar was slightly too high and that it should be taken away and the back thinned. This Bayer refused to do, knowing that thinning would only throw the entire instrument out of balance. “Maestro,” he said, “if you’re not completely satisfied with this guitar, then I have other clients who want to buy it.” Bream exploded and asked Bayer to leave, which he did — with an instrument in each hand.

Back in the workshop under close examination, Bayer discovered the full extent of the damage to the first Bream guitar: ribs had sprung loose; there were hairline cracks around the sound-hole and the table edges and signs that other joints had been compromised. He then remembered that the shipping crate had sat on the tarmac during a heatwave and that the guitar had obviously been cooked. He tried to explain this in several letters to Bream, who never replied. Bayer then filed a claim with the courier, who refunded the guitar’s full value. It might have been repaired but, feeling his masterpiece had been trammeled, first by heartless Mother Nature and then by a famous English guitarist, he never touched it again.

Bream and Bayer were equally stubborn and temperamental, eminent in their respective arts, so perhaps a spectacular falling out was inevitable, whether or not a masterpiece had been ruined by excessive heat. Bayer completed 13 guitars in all before retiring as a luthier in 1989. Each is superb visually and tonally, highly prized by its owner.

David Bayer was a meteor. He remains unaware of just how gifted he was, since meticulous craftsmanship, brilliant engineering solutions, and a hypersensitive ear are second nature to him. His best instruments have something extra: a Gestalt that makes them “objects of desire.” His legacy is his output, and all of the surviving instruments deserve to be preserved and maintained for posterity.

After two decades of making musical instruments, Bayer became a successful mechanical engineer. The only senior member of his companies without an academic degree, he was nevertheless relied upon to solve the most difficult design problems. He holds two United States patents and one from the European Union for alcohol breath-testing devices. Retired and still living in St. Louis, Bayer now devotes his time to building and testing model rocket engines.

A complete catalogue of the instruments can be found at www.charlesjmetz.com, “About the Builders,” as well as links to other performances featuring harpsichord no. 11.

Curtis Price, a native of Springfield, MO, was principal of the Royal Academy of Music in London 1995-2008 and warden of New College Oxford 2009-16. While a graduate student at Harvard in the late 1960s, he assisted Frank Hubbard as curator of the Music Department’s historic keyboard collection and worked briefly as an apprentice for harpsichord maker William Post Ross. During his career as a music historian, Price published many books and articles on Baroque music and historic performance practice. He was knighted by the Queen in 2003 for services to music. In retirement and living in Snowdonia, north Wales, Price is once again making harpsichords.