by Naomi Dumas

Published March 18, 2019

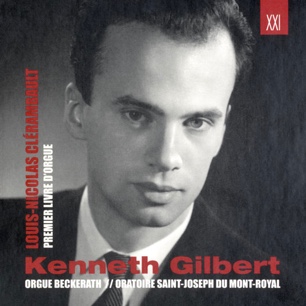

(Photo by Jean Guimond)

The history of La Belle Province can be traced to the dawn of the Baroque period with the founding of Quebec City by Samuel de Champlain in 1608, making it the first permanent French establishment on the North American continent. Montreal was founded in 1642, three years after the birth of Louis XIV in France. With concern for his Nouvelle France across the Atlantic, the Sun King would make it a Royal Colony in 1663 and appoint Jean Talon as its first intendant, greatly contributing to its growth and economic flourishing.

Music played a central role in the religious and cultural life of the colony. Works by French composers De Cousteaux, Fremart, Lebègue, Jacquet de LaGuerre, and Campra were brought and performed in church, and new ones were composed, as confirmed by the more than 160 manuscripts that survive from this period.

The court’s greater concern for local interests and natural resources from the Antilles, however, left the American colonies destitute against the surrounding British army. Following four years of war, Britain took over in 1763 and baptized the territory as the Province of Quebec (Algonquin for “where the river narrows”), subjecting its population to strict assimilation rules. Despite those efforts, the area remained mainly French-speaking, as British subjects preferred settling in other areas, and the Act of Quebec was passed in 1773, giving back formerly denied rights to the francophone population. From then into the mid-20th century, they would have to fight for equal rights and cultural freedom.

The court’s greater concern for local interests and natural resources from the Antilles, however, left the American colonies destitute against the surrounding British army. Following four years of war, Britain took over in 1763 and baptized the territory as the Province of Quebec (Algonquin for “where the river narrows”), subjecting its population to strict assimilation rules. Despite those efforts, the area remained mainly French-speaking, as British subjects preferred settling in other areas, and the Act of Quebec was passed in 1773, giving back formerly denied rights to the francophone population. From then into the mid-20th century, they would have to fight for equal rights and cultural freedom.

The Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837 (also known as the Patriot’s War) stands among one of the most notable conflicts, and notary J. J. Girouard, involved in the Rebellion, was also the owner of a rare manuscript of organ music imported from France in 1724. Recently rediscovered, the Livre d’Orgue de Montreal contains 398 religious works composed by Nicolas Lebègue (1630-1702) and anonymous organists of the French court.

The early-music revival in Quebec was initially kindled by an interest in keyboard music. The Ars Organi society was founded in Montreal in 1960 by young and upcoming organists including Bernard Lagacé, Kenneth Gilbert, Raymond Daveluy, and Gaston Arel to present concerts that honored the highest traditions of organ music. Classical-style organs with tracker action were commissioned from German maker Rudolf von Beckerath and installed in three of the city’s main churches; these rare replicas were soon put to use for the society’s recitals and played by local as well as international artists.

The society succeeded in generating a renewed interest in organ playing and building around Canada, sparking the curiosity of a new generation of performers to dig deeper into performance traditions. Gilbert was the first in the province to obtain and play harpsichords based on early models. After winning the Prix d’Europe for organ in 1953, he studied at the Paris Conservatoire with Nadia Boulanger (composition), Maurice Duruflé, Gaston Litaize (organ), and Ruggero Gerlin (harpsichord). Stephen Plaistow, in a 1973 Gramophone article, stated that “Kenneth Gilbert’s achievement…is to rescue the music from a small circle of connoisseurs and to make it…universally enjoyable…”

Coinciding with the culmination of Quebec’s Revolution Tranquille (1960-1975), which led to some of the province’s greatest political efforts to obtain long-sought-for independence from the rest of Canada, an increasing awareness of the non-conformist early-music movement in Europe started spreading in the province as recordings were made available in the early 1970s. Among Montreal’s musicians interested in these historically informed recordings were organist and choirmaster Christopher Jackson, organist Hélène Dugal, and organist-harpsichordist Réjean Poirier (first-prize winner of the Bruges competition on organ in 1973). It was during a train ride in France in 1974 that they came together to found the Studio de Musique Ancienne de Montréal.

The SMA Montréal is one of the city’s first early-music ensembles. Starting as a 10-13-member vocal group, it brought in instrumentalists from around the area who sought to break from the mainstream. In a spirit of curiosity and collaboration, they experimented with early styles and techniques through historically informed renditions of early Baroque choral works. Introducing a lost language from another time through a new form of performance, the ensemble soon gained recognition for its “high musical and musicological quality” (Claude Gingras, La Presse, 1975), along with an increasing interest in the style of performance among audience members (including today’s internationally acclaimed soprano and early-music specialist Suzie Leblanc). The group has released 17 recordings and presents an average of four concerts per season led by choral conductor Andrew McAnerney, who was appointed in 2015.

In 1978, two years after the first election of the Parti Québecois (separatist political party), the Ensemble Anonymus was formed in Quebec City by multi-instrumentalist Claude Bernatchez (its principal repertoire dating from the Medieval era). The Ensemble Nouvelle France was formed the same year by flutist and musicologist Louise Courville. It presented historical performances of repertoire composed in the Nouvelle-France from its founding to the end of the 19th century. A founding member, harpsichordist Richard Paré, was also involved in starting one of Quebec’s most reputable chamber ensembles, Les Violons du Roy. Taking its name from the French court’s orchestra, it was founded in 1984 by Bernard Labadie as a chamber ensemble and now comprises some 15 musicians playing modern instruments with stylistically appropriate bows. It is one of the province’s most successful groups, with a full-time season based in both Quebec City and Montreal, concerts abroad, and performances with early-music notables, including Philippe Jaroussky, Anthony Marwood, Isabelle Faust, and Julia Lezhneva.

The recording industry and radio broadcasts (for CBC and Radio Canada) were major contributors to the development and growing popularity of Montreal’s early-music scene from the 1970s into the ’80s and provided a stable revenue for many of the city’s performers. Growing interest in historical performance was cultivated in music schools as well, largely within the halls of McGill University. A program was formed by professors John Grew (harpsichord) and Mary Cyr (gambist and musicologist, who studied with Anner Bylsma and Wieland Kuijken) in the mid ’70s. Due to sufficient funds, they established a baroque orchestra in 1978, long before many other schools in North America. Only a year later, the early-music program at the Université de Montréal was initiated by newly appointed professor of music Réjean Poirier.

Students involved in this early stage of the McGill program included harpsichordist Hank Knox, flutist Claire Guimond, and gambist Betsy MacMillan, founding members of the Arion Baroque Orchestra. The ensemble started in 1980 as a five-musician chamber group comprising those players and British tenor Edmund Brownless and violinist Chantal Rémillard. Arion launched its first season in 1981, attracting a young audience and presenting repertoire not often performed by other early-music groups in the city. It quickly achieved wide success, receiving positive recognition by Quebec’s top critics and, in 1984, was awarded third prize at the Concours international de Musique de Bruges. Arion has since expanded to include more than 20 musicians playing period instruments, and it collaborates with such internationally renowned guest artists and conductors as Stefano Montanari, Monica Huggett, Jaap ter Linden, Rachel Podger, and Barthold Kuijken. Its five-concert Montreal series is based at the Salle Bourgie of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, with three to four representations for each. Its discography includes more than 32 titles, many of which have been nominated for or won awards.

As ensembles grew, Montreal started attracting more and more artists from abroad, not only as guests, but as city dwellers. Drawn for its musical centrality and the room it offered for creativity, Bruce Haynes and partner Susie Napper moved there in the 1980s and contributed to its early music scene in colossal ways. Born in Kentucky, Haynes pursued studies at The Hague Conservatory with Frans Brüggen and Gustav Leonhardt. Oboist, recorder player, composer, instrument maker, teacher, and musicologist, Haynes is recognized most for his contribution to the revival of the hautboy, standing among the first 20th-century performers to master the instrument and responsible for its re-introduction to Europe in the mid-1970s. Haynes completed a Ph.D. at the Université de Montréal and published numerous books, including A History of Performing Pitch: The Story of A (Scarecrow Press, 2002) and The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century (Oxford University Press, 2007).

(Photo by Tobias Haynes)

Haynes, who died in 2011, and Napper were founding members of the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra in San Francisco (1981). Considering herself a “rebel to the core,” London-born gambist Napper started her studies on cello at the Juilliard School before returning to Europe to pursue studies in historical performance. An active performer and teacher in Montreal, she founded the ensemble Les Voix Humaines and the Montreal Baroque Festival, teaches at McGill University, Université de Montréal, and the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen, received an Opus prize as Personality of the Year in 2002, and was recognized as a “Femme de Mérite” in Montreal in 2011.

The virtuoso German recorder player Matthias Maute, first-prize winner of the Bruges Early Music Competition in 1990, founded Ensemble Caprice in Germany in 1989 before moving to Montreal a few years later. His group would evolve into one of the city’s most highly recognized ensembles, appearing at some of the world’s most prominent early-music festivals, such as Utrecht and Bruges. The baroque orchestra is known for its innovative spirit, venturing into lesser-known repertoire, including works by contemporary composers, and pushing boundaries of performance practice. Although the musicians play period instruments, Maute doesn’t shy away from hiring soloists who play modern instruments, and he is involved in projects with modern orchestras.

Montreal’s international reputation as a cultural metropolis has been greatly enriched by the Montreal Bach Festival, founded in 2005 and recognized from its start as one of the city’s major artistic events. Presented mid-November to early December, the festival offers concerts, lectures, and musicological symposiums in major (and lesser known) venues. The Montreal Symphony Orchestra and its music director, Kent Nagano, are the festival’s official partners, and a variety of performance mediums, including dance and jazz, and educational workshops have held a prominent place in the programming.

In some respects, the early-music scene in Montreal today is quite like that of New York, with numerous small, part-time ensembles that share freelance musicians and performance venues. In addition to the orchestras mentioned above, other ensembles include La Bande Montreal Baroque (led by Eric Milnes), Les Idées Heureuses (founded by harpsichordist and musicologist Genevieve Soly in 1987 and the first ensemble in Quebec to present Baroque dance as part of its performances), and Les Boréades de Montréal (founded in 1991 by recorder player Francis Colpron and creator three years ago of a three-day workshop on historical performance practice). Other emerging ensembles include Pallade Musica and Flûtes Alors! As Montreal stands out from the rest of the province of Quebec due to its prominent English population, collaboration between both anglophone and francophone artists has been a natural and apparent part of its culture.

Aside from McGill’s early-music program, which offers degrees at the undergraduate and graduate levels and boasts an impressive faculty for all historical instruments, the Université de Montréal also has programs specializing in period instruments and shares many of its professors with McGill. The Conservatoire de musique de Montréal does not offer programs in historical performance, but it does have a harpsichord degree taught by Luc Beausejour, who also leads a baroque ensemble. The conservatories in Quebec City and Saguenay have on their string faculty members of the Arion Baroque Orchestra and Les Violons du Roy, although no lessons are officially offered on period instruments.

One remarkable trait of the early-music scene in Montreal is its diversity, attracting artists from around the world, mixing French and English-speaking populations, historically informed as well as modern instruments and ensembles, and presenting old and contemporary works. Montreal’s affinity for artistry and creativity has made way for the development of numerous early-music ensembles since the mid-20th century. The movement continues to flourish as the city has gained ground on the global scene with the institution in 2005 of the Montreal Bach Festival and in September 2011 of the opening of the Bourgie Hall at the Museum of Fine Arts, attracting reputable conductors, performers, and ensembles from around the world, and making way for its own artists to be recognized.

For the rest of the province (aside from Quebec City’s quasi-baroque Les Violons du Roy), there is still a lot of room for growth and development. As Hank Knox says, the future of early music in Quebec resides in the hands of the next generation of performers, so it’s up to us to see it progress and thrive.

Originally from Quebec and based in New York City, baroque violinist Naomi Dumas has appeared with ensembles including La Bande Montréal Baroque, Juilliard415, and Bach Collegium Japan. She is pursuing a graduate degree as a full scholarship student at The Juilliard School in Historical Performance.

The author would like to thank Réjean Poirier, Claire Guimond, Hank Knox, Helene Plouffe, Susie Napper, and Nicole Trottier for their assistance in providing valuable information. Special thanks to Professor Thomas Forrest Kelly from the Juilliard School, for whom this was originally written as a final paper for the course “Studies in Historical Performance.”