by Karen M. Cook

Published August 28, 2023

Early music shows up in everyday, often unexpected, places. Historical tunes have long been common in movies and on television, from the Dies Irae in It’s a Wonderful Life to music by Thomas Tallis in HBO’s The Tudors. Less obvious to many, early music abounds in video games. And thousands upon thousands of games are set in the medieval or Renaissance eras or a fantasy world that creatively reimagines the distant past à la Tolkien. Many of them incorporate some sort of early music or early instruments into their soundtracks, and since even the shortest video games often take longer to play than the length of an average film, there is quite a bit of music to ponder. It’s worth noting, too, that video games generate more revenue than the global film industry.

Early music in games can appear in different ways and for different purposes. The recognizable Dies Irae — a piece of music that over centuries has become inextricably linked with the supernatural, fear, horror, and death — shows up in modern media to imply that something is afoot. In a few games, such as the 1992 PC game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis or the 1993 horror parody Zombies Ate My Neighbors, the chant is heard when the main protagonists confront the final evil boss. It also appears in the title track to F-19 Stealth Fighter (1988–92), although here it acts as a tense reminder of the battles, and likely deaths, the player will engage in.

Shorter polyphonic pieces that a player might recognize can also appear; for example, the main theme for the Henry VIII simulator Fit for a King (2019) is a retro chiptune version of “Pastime with Good Company.” Another popular choice is “Greensleeves” (or the later “What Child is This?” hymn version), showing up in the soundtracks for games such as Anno 1602 (1998) in order to evoke a general sense of past-ness and, possibly, European-ness, or even Englishness.

But video games have come a long way fast. As technology developed, consoles were able to incorporate samples of pre-recorded audio. Soundtracks could thus include short excerpts of vocal or multi-instrumental music, either by themselves or layered in as part of a larger track. In fact, collections of such short excerpts, known as sample libraries, became popular tools for game composers in the 1990s and 2000s. Some targeted the sounds of early music, offering composers sets of chant snippets and early instrument timbres. The bits of chant were often used for flavor, in a manner of speaking, not in any sort of textually coherent manner. For example, the theme for Helm’s Temple in Baldur’s Gate (1998) uses the melisma on “haec” from the chant “Haec dies” and a cadential “Amen.” A random vocal “Osanna” appears during the “Cathedral Spires” theme in MediEvil 2 (2000), for example, while the recognizable open-fifth leap of a mode 1 “Alleluia” incipit forms a melodic theme in the instruments. And the track called “Amen” from Medieval II: Total War (2006) combines the aforementioned “Osanna,” the mode 1 “Alleluia” (now sung), and the same cadential “Amen”!

Rather than using sample libraries as a compositional tool, other games took advantage of the digital ability to emulate different timbres. (For anyone who has ever owned an electric piano with a variety of “instruments” to select from, it’s the same principle). Listen, for example, to a “recorder consort” perform Thoinot Arbeau’s “Belle qui tiens ma vie” in Anno 1503 (2002).

The use of entire pre-recorded tracks also became possible through advances in storage capacity, and this musical strategy pervades throughout decades of game soundtracks. As a sonic background to the Johannes Gutenberg case in Carmen Sandiego’s Great Chase Through Time (1997), for example, we hear Hans Neusidler’s 1536 lute passamezzo “Wascha mesa” (at 46:35). Dozens of early-music recordings, from plainchant to Mass movements by Ockeghem, Brumel, and Palestrina to Ortiz recercadas to Allegri’s famous Miserere, are heard in the background during the “Medieval” era in Sid Meier’s Civilization IV (2005).

The more recent humorous Renaissance art-based games Four Last Things (2017) and The Procession to Calvary (2020) are chock full of early music: the player can interact with musicians who perform works such as John Dowland’s “Can She Excuse My Wrongs” or a Scarlatti sonata “on a harp that sounds suspiciously like a guitar” (as the game character describes), or listen to a recorder consort play Thomas Morley’s “Though Philomela lost her love.” And in Sid Meier’s Civilization V: Gods and Kings (2012), composer Geoff Knorr uses a modern reworking of the Kyrie of Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame as a transition into the Renaissance era.

One of the most recent early music-riddled games is Pentiment (2022), with a soundtrack by medieval ensemble Alkemie. A mystery set in 16th-century Bavaria, the player must solve various murders to the strains of works such as “Fortuna desperata,” “L’homme armé,” and Hildegard of Bingen’s “Quia ergo femina.” The latter track is heard when engaging with the character Sister Amalie of Völklingen, an anchoress and mystic who lives enclosed next to the town church — a sly cameo by Hildegard herself, who also appears as an enemy to defeat in the strategy marginalia game Inkulinati (2023).

In addition to hearing various and sundry early works as a game’s theme song or as part of its soundtrack — something heard in the background — early music can also appear in games as something the player themselves has to “perform.”

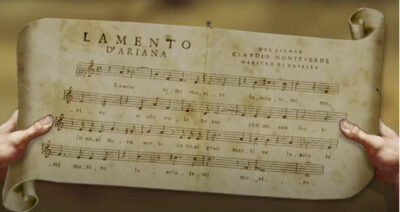

One particularly robust example is in the aforementioned The Procession to Calvary. In one area, the player must successfully “sing” “Lasciatemi Morire” from Monteverdi’s lost opera L’Arianna by clicking on the correct lyrics in a timely fashion (at 44:33).

Contrast this with the act in Assassin’s Creed: Revelations (2011) in which main character Ezio Auditore must disguise himself as a lute-wielding minstrel, although here the music is newly composed for the game; Ezio then must use the lute as a weapon to assassinate the final threat in this area.

As with this latter example, many games don’t arrange a pre-existing piece but rather conjure a sense of “earliness” through chant-like monophony, modal harmonies, dance-like rhythms, early instrument timbres, and style of language. Chant, drones, and parallel fifths are often associated with religious scenarios, as in Touché: The Adventures of the Fifth Musketeer (1995), Anno 1404 (2009), or Mission 1545 (2017), while scenes involving taverns or drink usually feature medievalist dances, as in Baldur’s Gate or Kingdom Come: Deliverance (2018). The compound meter, modal cadences, and rhythmic gestures of “Greensleeves” are imitated in tracks throughout games such as Romeo Wherefore Art Thou (2010) and The Guild 2, while the menu theme of the 1995 strategy game Machiavelli: The Prince (at 0:52) is reminiscent of works found in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch.

And madrigal-like songs occur in numerous games, from Assassin’s Creed: Revelations to the quirky time-loop take on Hamlet Elsinore (2019), but nowhere as abundantly as in the comedy narrative game Astrologaster (2019). Here, the sixteenth-century astrologer-physician Simon Forman consults the stars in order to diagnose local patients, and each new patient is introduced by a custom madrigal, often quite humorous, in the style of Thomas Morley or William Byrd. (More religious patients, though, might be introduced by something more like a Tallis anthem.)

Video games creatively employ early music not only as background music, meant to establish a general sense of time and place, but also as an active element in gameplay, meant to engage the player in the act of music-making, in a manner of speaking. Furthermore, games — like films and television — provide composers with opportunities to re-imagine not what the past might have sounded like then, but what it could sound like now. From newly composed music in the style of past genres to fresh arrangements of old standards, games allow people yet another way to “play” early music.

Karen M. Cook is Associate Professor of Music History at the University of Hartford. She specializes in late medieval music theory and notation, focusing on developments in rhythmic duration. She also maintains a primary interest in musical medievalism in contemporary media, particularly in video games.