by Donald Rosenberg

Published February 11, 2020

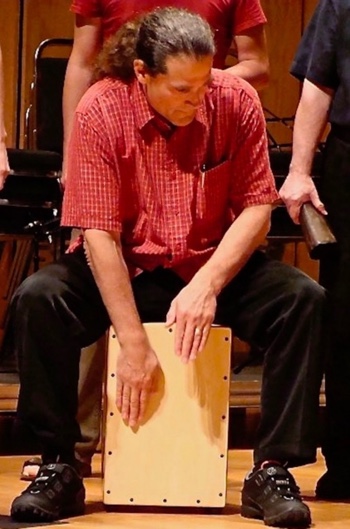

People who knew and worked with Tom Zajac speak about the late multi-instrumentalist and educator with equal amounts of affection, admiration, and reverence. Zajac (1956-2015) performed with eminent early-music ensembles on an abundance of wind and percussion instruments from many cultures, and he was always searching for new ways to make artistic connections.

The curiosity and adventure he brought to his endeavors is being celebrated by Early Music America with the establishment of the Thomas Zajac Memorial Scholarship. The biennial scholarship is open to “early music performers and scholars who wish to pursue specialized study in ethnic and/or folk traditions, instruments, or styles, for the purpose of exploring cultural cross-fertilizations in the history of early music and bringing that knowledge to bear in historically-grounded scholarship and performance.” Deadline for online applications is April 4, with letters of recommendation due April 10. One award of $1,500 will be announced on May 4.

The scholarship has been spearheaded by soprano Nell Snaidas, who was a student of Zajac at the Mannes College of Music before she became a colleague. “Tom was my first collegium director at Mannes,” Snaidas said. “He had just graduated and was working a lot with Paul Echols, who was a mentor to Tom and Grant Herreid and Jolle Greenleaf and Adam Gilbert, and many more. Tom had the collegium and asked me to join for a semester to do a Monteverdi quintet. He was amazing. He was one of the reasons I got into early music at all.”

Snaidas recalls attending a Mannes Camerata performance of Roman de la Rose in which Zajac was a cast member. “I’ll never forget Tom coming out — he looked like a prince. He had tights and a tunic and this jet-black curly hair and ivory skin and piercing blue eyes. You couldn’t believe that a tapestry had come to life. He picked up a recorder and then a tabor. The world came alive when I saw him. I said, ‘I want to step into that world and have that feeling.’ You always had the feeling with him, whether he was in costume or not. We became friends and lifelong colleagues.”

Zajac also served as director of the Collegium Musicum at Wellesley College, where his colleagues included Lawrence Rosenwald, a professor of English with long experience in early music. The first project Zajac undertook there was a performance of Hildegard’s Ordo Virtutum, in which Rosenwald played the devil. “I’ve worked with a lot of really gifted and accomplished musicians, and I’ve known very few with as little of an agenda or obstreperous ego as Tom,” said Rosenwald. “He wanted to work on the project with people who wanted to work with him.”

Zajac collaborated with students and professionals for more than three decades, during which he was a member of Piffaro, co-founder of Ex Umbris, and a frequent performer with such ensembles as the Newberry Consort, Waverly Consort, Folger Consort, and the Boston Camerata. He visited dozens of countries to learn about their musical traditions and bring back instruments new to him and to listeners who would hear him play them.

“When he was with colleagues in a new city or another country, he was often someone who would mobilize people to go on some adventure and explore something they may not have done otherwise,” said Lilli Nye, Zajac’s widow. “He also had a special interest in the early-music field in how diverse cultures throughout historical events would come into contact and what musical forms would be born out of that. As an early music multi-instrumentalist and scholar, those cross fertilizations were particularly exciting to him.”

Nye, a marriage and family therapist in Albuquerque, NM, tells an anecdote that reveals much about Zajac’s inquisitive nature. “When I was going through his belongings, I came across a box of postcards. They were from various cities and town and locations around the U.S. or the world — ‘Wish you were here’ cards. I recognized some of the people who had sent these postcards. I asked his sister about them. She said from the time he was a little kid, he wanted everyone to bring postcards of any place they’d ever been to. He came into the world with a curiosity about the world beyond his horizon. That just flourished into this career of a musician who visited many, many countries. That desire to know the world was intrinsic to him. I feel that’s linked to the idea of the scholarship — his sense of being a citizen of the planet and curious about other cultures and other places. It got refined and focused over time, but it just was that really being a part of him as a person.”

Friends of Zajac began raising money for him during treatments for recurring brain tumors in the hope that he would recover. After his death in 2015, Nye decided she wanted to donate money to the early-music community, which had been Zajac’s family. Snaidas suggested using the funds for EMA to create a scholarship in his name. To date, nearly $35,000 has been raised.

“Tom Zajac’s early music journey through musical and geographical landscapes made him a pied piper of sorts to so many musicians, and all of us at EMA are thrilled that we’re able to honor him in perpetuity through this fund,” said Karin Brookes, executive director of EMA. “It’s particularly poignant that so many friends, colleagues, and fans contributed to it during Tom’s life and have continued to do so during the last two years.”

For Snaidas, the fund is an important link between the past, the present, and the future. “I think a lot about legacy, about all the people who are precious to us,” she said. “I had lost my father [Adolfo Snaidas, professor of Latin American Literature and Cinema at Rutgers University] several years ago, and colleagues had set up a scholarship in his name where he was a professor. That meant a lot to us. I thought we should have a scholarship in Tom’s name for someone who is interested in things the way he was interested in things.”

Nye is also pleased that the scholarship will honor her husband’s generous spirit. “Someone said, ‘Tom never met a stranger.’ He was great at making friends and giving people his full attention. There was a lot about him I didn’t know until when he was really sick. Praises began to pour in for him from Facebook. I knew him just personally. I began to understand what he meant to his community of colleagues, students, fans. He was just sort of universally loved. A lot of people talked about despite the fact that he was a minor celebrity in the early-music field, he never saw himself that way. He saw himself as a peer of everyone who was learning music.”

Donald Rosenberg is editor of EMAg.

Learn more about how EMA supports study in the field of early music through Biennial Scholarships and Annual Workshop Scholarships.

To make donation to the Zajac Memorial Scholarship Fund, please use this contribution form and designate the Zajac fund in the appropriate field.