by

Published March 16, 2018

Curious and Modern Inventions: Instrumental Music as Discovery in Galileo’s Italy. Rebecca Cypess. University of Chicago Press, 2016. 307 pages.

By Ambra Casonato

BOOK REVIEW — In Curious and Modern Inventions, Rebecca Cypess takes a highly original approach to early modern Italian instrumental music, situating her study in the context of scientific curiosity in the early 17th century. At the heart of her argument is what she refers to as the “paradox of instrumentality,” in which performers are able to move the affections of the listeners through experimentation with the technological limits of their instruments.

The book, divided into six chapters and accompanied by an introduction and a conclusion, discusses instrumentality through a variety of disciplinary perspectives. The first two chapters deal with the role of the artisan-performer who creates meraviglia (marvels) and moves the affetti (affections) through material objects, the instruments. The third and fourth chapters shift the attention to the representation of music, drawing parallels with the visual arts. The final two chapters tackle the issue of timekeeping and the differences between public and private time during the early modern period.

The book, divided into six chapters and accompanied by an introduction and a conclusion, discusses instrumentality through a variety of disciplinary perspectives. The first two chapters deal with the role of the artisan-performer who creates meraviglia (marvels) and moves the affetti (affections) through material objects, the instruments. The third and fourth chapters shift the attention to the representation of music, drawing parallels with the visual arts. The final two chapters tackle the issue of timekeeping and the differences between public and private time during the early modern period.

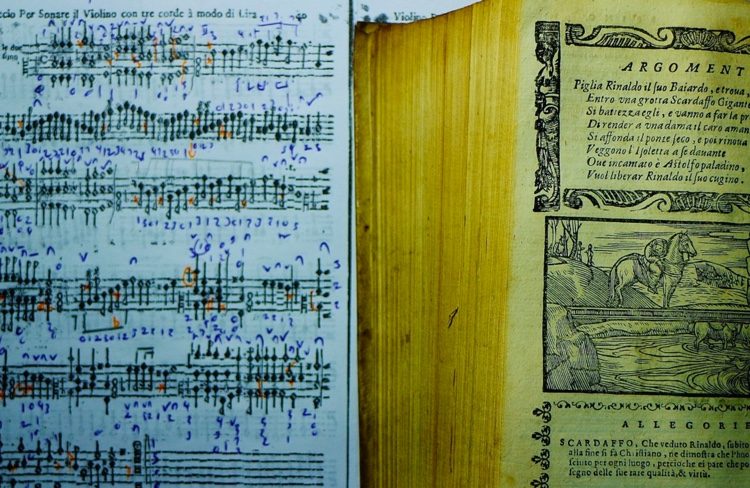

Cypess focuses on a core repertoire she presents in multiple contexts throughout the book. These include some of the most significant printed compilations of instrumental music from the period: Biagio Marini’s Sonate, symphonie, canzoni (1626) and Affeti musicali (1617), Carlo Farina’s Capriccio Stravagante (1627), and Girolamo Frescobaldi’s Toccate e partite (1615), among others. The author masterfully weaves her examples into this multidisciplinary framework, with reference to vocal music, literature, visual arts, and science. For example, she compares Marini’s Affetti musicali, in which the titles of each piece invoke the names of specific people, to the catalog of paintings collected by the Venetian Andrea Vendramin. Both had the aim of stirring the affetti of viewers or listeners and to encourage “the cultivation of the kind of sociability” advocated by contemporary commentators.

This informative and easy-to-read book, moreover, does not solely focus on the musical aspects of early modern style, but puts music in the broader context with a fresh and new take on the development of instrumental music in the early 17th century. The work is based on an extensive selection of primary sources as well as the most recent scholarship, with a copious bibliography that will be of value to scholars and musicians.

There are a few instances, however, in which a greater understanding of the technical aspects of Baroque violin playing would have been helpful. For example, Cypess uses Marini’s Sonate, symphonie, canzoni to show how performers moved the affetti of listeners by “inventing” new techniques as well as “re-inventing” and “altering” musical instruments. While this is a sound argument, some of the chosen examples do not support her claims. In Marini’s “Sonata d’Inventione,” for example, the author isolates a passage involving scordatura tuning and claims that this retuning of the violin is a way to “facilitate unusual double-stops,” adding further that with this alteration, the performer is able to play the entire passage in first position. However, the passage turns out to be much more difficult when the scordatura is applied, requiring the musician to go up to the third position. The problem is compounded by the fact that Marini notates the sounding pitches in this scordatura passage, rather than supplying the correct fingerings that would have allowed the player to produce the proper notes (as, for example, Biber does in his Rosary Sonatas).

Nevertheless, Cypess reveals her prowess in handling keyboard music when analyzing Frescobaldi’s works in the last two chapters of the book. For instance, she utilizes Frescobaldi’s first and second editions of the Primo libro delle canzoni (1628 and 1635, respectively) to show how the awareness of timekeeping in both music and everyday life increased during the first decades of the 17th century. Comparing the two prints, she demonstrates how time-consciousness, which increased in the early modern period, was reflected in the 1635 edition. At a time when people felt the need to structure their day mathematically, relying on pocket watches instead of town clocks, Frescobaldi felt the necessity to introduce additional tempo markings in his second edition of the Primo libro delle canzoni to regulate the flow of music, while still allowing freedom for the expression of the affetti.

This is an engaging book that provides a solid foundation for future research. For performers, violinists, and keyboard players in particular, it is an invaluable contribution to the study of early modern instrumental music, a topic that has not been treated as thoroughly as its vocal counterpart. Yet this book does not solely focus on early 17th-century music in isolation. The unique characteristic of Curious and Modern Inventions is to be found in its interdisciplinarity, in particular the parallels and connections she draws between science and art. This trait, typical of early modern thinking, enables Cypess to educate her readers in a contextualized manner, making this book accessible to amateurs and music lovers alike.

Ambra Casonato is a second-year graduate student in musicology at Princeton University. She is also an active modern and baroque violinist, and holds a master’s degree in Historical Performance from the Juilliard School.