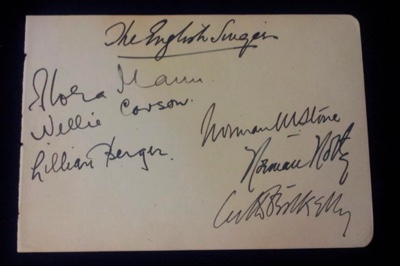

(Photo courtesy of the Oberlin Conservatory Library Collection of Musicians’ Autographs and Photographs)

By Anne E. Johnson

In 1925, American concertgoers got a treat. A six-member a cappella vocal group from Britain, The English Singers, gave their first concert Stateside, at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Audiences loved their early-music repertoire (although “early music” was not yet a designation). So did the talent scouts for a company called Roycroft, which was experimenting with a more natural-sounding technique of recording the human voice. The English Singers made a 12-disc set of 78 rpm records for the Roycroft “Living Tone” line, released in 1928. And now anyone with an internet connection can hear most of it.

The Great 78 Project is a collaboration between the ARChive of Contemporary Music and the Internet Archive. Donated 78 rpm discs numbering about 200,000 are being digitized, catalogued, and made available for streaming and download. The preponderance of entries are various types of popular music, but there is some classical. And one of the most surprising finds is 22 sides by The English Singers.

The group was formed in 1917 as a quartet by bass Cuthbert Kelly, with two more singers added in 1920. Kelly remained the group’s spokesman throughout their long career (into the 1950s). On some of the early recordings he speaks an introduction to the piece they’re about to sing. For Orlando Gibbons’ madrigal “The Silver Swan,” that includes a complete recitation of the poem:

https://archive.org/details/78_the-silver-swan_the-english-singers-orlando-gibbons_gbia0017700a

Besides the blare of static from the 1928 record’s surface, you’ll also notice an approach to singing 16th-century music that does not align with today’s expectations. In his 1988 book The Early Music Revival: A History, Harry Haskell bemoans The English Singers’ “flaccid rhythm and unfocused tone.” I’m not sure there’s much point to judging these early-music pioneers by more recent performance-practice standards. Their very existence — and the existence of these recordings — makes them important in music history.

Nor is their approach to scholarship the same as today’s. The English Singers did not work from manuscripts or facsimiles, but from published performance editions, mainly by Elizabethan scholar Edmund Fellowes. Haskell describes Fellowes as “largely responsible for Elizabethan fever that swept across the country in the week of the first world war.”

The Roycroft 78s include several of the (now) best-known English composers of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Thomas Morley is represented several times, including “Sing We and Chant It,” which the group identifies as a “ballet” (consistently their spelling for ballad):

The Roycroft 78s include several of the (now) best-known English composers of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Thomas Morley is represented several times, including “Sing We and Chant It,” which the group identifies as a “ballet” (consistently their spelling for ballad):

https://archive.org/details/78_sing-we-and-chant-it_the-english-singers-thomas-morley_gbia0017702b

We get an idea of their reverence for these composers by reading Word Book of the English Singers Music. This booklet was published as a supplement to the 78s series, but mailed separately to listeners who requested it. I had a chance to view it in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts special collections. “Sing We” is introduced by the following encomium:

“Morley was the first to use the name madrigal as he was also the first to introduce the ballet into English music.” That questionable claim then leads to a gush of nationalism typical of the commentary for this collection: “The art of singing in harmony, the form for modern composing and the beginnings of instrumental music— all can be traced to England [sic] musicians.”

Never mind the Italians, French, or Flemish.

Another of The English Singers’ heroes is William Byrd, who, they aver, “invented the musical form of composition which has been the foundation for all the great composers who followed him.” Those words introduce his 1588 part-song “Though Amaryllis Dance”:

https://archive.org/details/78_though-amaryllis-dance_the-english-singers-william-byrd_gbia0017693b

Although The English Singers were often referred to as performers of Elizabethan music, their repertoire stretched beyond that designation. They made the first-ever recording of “Sumer Is Icumen In,” giving attribution for the 13th-century rota to John of Fornsete, in accordance with 19th-century scholarship:

https://archive.org/details/78_sumer-is-icumen-in_the-english-singers-john-of-fornsete_gbia0017694b

“Sumer,” says the Word Book, is “absolutely unique in the history of music. It is the first song to have a separate part for each voice; the beginning of counterpoint, the formula for all modern musical composition!” Yes, the exclamation point is theirs. That gives you some idea of the enthusiasm they had for sharing this music with the unannointed.

On the more recent side of the Elizabethan era, we have “The Three Fairies” by Purcell, a composer the commentary declares “should be linked with Byrd and Gibbons as the immortal trio of great English composers.”

https://archive.org/details/78_the-three-fairies_the-english-singers-henry-purcell_gbia0017700b

Sadly, there’s an irregularity in the tracks available on The Great 78 Project that cheats us out of two songs by Thomas Weelkes, another English Singers favorite. When I noticed that searching for “English Singers” yielded 22 songs but the Roycroft Word Book listed 24 sides, I assumed that one disc was missing when the recordings were donated to the internet project. A little detective work indicates that there were multiple editions of the 78s; the discs donated to The Great 78 Project and the Word Book at NYPL don’t match.

For example, Weelkes’ “Hark All Ye Lovely Saints” is identified in the Word Book as the first side of Record No. 158, whose other side is the carol “We’ve Been Awhile A-Wandering,” arranged by R. Vaughan Williams. The internet archive includes that carol, but they say (with a photo of the label as proof) that the other side of Record No. 158 is a folk song called “An Acre of Land,” also arranged by Vaughan Williams:

For example, Weelkes’ “Hark All Ye Lovely Saints” is identified in the Word Book as the first side of Record No. 158, whose other side is the carol “We’ve Been Awhile A-Wandering,” arranged by R. Vaughan Williams. The internet archive includes that carol, but they say (with a photo of the label as proof) that the other side of Record No. 158 is a folk song called “An Acre of Land,” also arranged by Vaughan Williams:

https://archive.org/details/78_an-acre-of-land_the-english-singers-r-vaughn-williams_gbia0017695b

The upshot of this discrepancy is that the tracks available to stream offer extra Vaughan Williams but no Weelkes.

It’s significant that Vaughan Williams is one of several then-contemporary British composers represented on the discs. In the beginning stages of the early-music movement, no clear distinction was made between pieces composed in early periods and modern arrangements that recast early material through a decidedly 20th-century filter.

Besides several such examples by Vaughan Williams, there are also heavily modernized contributions by Peter Warlock (pen name of composer and music critic Philip Heseltine), Rutland Boughton (who reportedly “formed a huge choral society of the townspeople of Glastonbury”), and Percy Grainger. The harmonies Grainger supplies for “Brigg Fair,” a folk song he collected on wax cylinder during field work in 1905, resettle it into the turn of the century:

https://archive.org/details/78_brigg-fair_the-english-singers-percy-a-grainger_gbia0017699b

In 1936, Cuthbert Kelly re-formed his group as the New English Singers, adding a lutenist (Nellie Carson). Fans of Benjamin Britten will be excited to learn that Peter Pears was one of the two tenors at that point. During the 1936 American tour, the New York Times reported that The English Singers’ visits had “caused the organization of various amateur groups throughout the country with similar purposes.” Kelly was quoted as saying that he often received letters asking advice on how to start an early-music ensemble. If that isn’t evidence of The English Singers’ significance to the early-music movement, I don’t know what is.

Critics were of mixed opinion on these new old sounds. A 1925 review in The Musical Observer praised “the beauty of the music and simplicity and sincerity of the presentation.” In 1936, Olin Downes of The New York Times remarked on the performance’s “fine technical values and aesthetic proportions.” But New York Post critic Samuel Chotzinoff didn’t buy it: “The very gifted Thomas Weelkes did not succeed in getting close to the anguished ballad ‘O Care.’ Even the great Purcell’s setting of two poems from The Tempest left one hankering after the unadorned text.”

Not just the music, but also The English Singers’ performance style was new to American audiences. Among the NYPL holdings is a press release of sorts, written by the group’s agent (one C.E. LeMassena) and seemingly intended both to interest venues in booking them and to provide marketing text to promote concerts. It seems The English Singers did not perform standing. Le Massena writes, “Seated about a table with the music before them, at which they barely glance, they sing with ease and joy indicating an authority which is magnetically reflected in the feelings of the audience.”

And why is it worth programming such an odd act? According to LeMassena, this old music has “long lain dormant but is now resurrected for the delight and entertainment of the 20th century blasé musical world.”

And why is it worth programming such an odd act? According to LeMassena, this old music has “long lain dormant but is now resurrected for the delight and entertainment of the 20th century blasé musical world.”

It’s hard for us EMA readers to imagine a time when early music was unknown. Listening to these Roycroft recordings gives us a glimpse into that era. But perhaps the best way to understand the wonder that filled listeners during The English Singers’ early U.S. tours is this description published in The Boston Transcript on Dec. 6, 1926. The critic, identified only by the initials “HTP,” articulates why the group and its repertoire are important, in terms that most of us will probably still agree with today:

“No such transparent music [as these Elizabethan madrigals] comes into the twentieth-century concert-hall, as clear as the day, as dappled with light and shadow…‘We moderns’ may envy them their flowing line, as of melody spontaneously released and up-springing; their elasticity of rhythm; their running voices meeting to part and parting to meet, luminous, meaningful, withal. It is rill; it is stream; it is rippling flood.”

It is early music, and we’re lucky that musicians such as The English Singers helped to give it second life.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in The New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.