by Karin Cuéllar Rendón

Published October 2, 2023

‘Why does the field need to change? The answer I go for is rooted in empathy: because we all deserve to be here.’

We’ve all seen worthy plans to advance IDEA values — inclusion, diversity, equity, access — in our ensembles and organizations, although many don’t go beyond a performative level of advocacy. It’s hard work to implement IDEA concepts. It requires constant listening, observation, adaptation, and renewal.

In Montreal, where I live, there are strong examples of classical musicians who keep these ideals in mind, on many levels. My own project, ClassiqueInclusif, follows the path created by several local artistic leaders.

One such ensemble, Infusion Baroque, is led by Thai-American violinist Sallynee Amawat. Their many illuminating projects include the Virtuosa Series, elevating women composers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Thinking more globally, their “East is East” combines Persian, Indian, and Western Baroque musical influences on traditional and period instruments.

“Our intention is to blur the lines between what we consider Western classical early music and world music,” says Amawat, “and to present early music in the context of a living tradition, similar to how traditional music is practiced around the world.”

Amawat, along with Thailand-based Canadian dancer Benjamin Tardif, also created an artists’ collective, called Compagnie Intangible, which explores early performance traditions of the East and West.

Their first project, a dance film titled Matchanu, pairs French Baroque ballet music with magical khon masked dance and classical Thai instruments to tell the ancient story of the deity Matchanu.

They are currently working on Lanna-Lanxang to explore the culture of the neighboring kingdoms of Lanna and Lanxang (Thailand and Laos). It’s a multidisciplinary performance that combines folk and hip-hop dance with contemporary and early music, performed on period instruments and electronics. While collaborating and learning from local musicians and dancers, they seek to reflect how present-day artists of the region view the Lanna/Lanxang culture as historic, evolving, inclusive, and intersectional.

“What’s great about diverse programs is that, regardless of what kind of audience you might perform for, someone will always have the opportunity to learn and appreciate something new,” Amawat explained when asked about attendance demographics.

One key point regarding inclusion, diversity, and representation is that it’s a two-way road: If we see ourselves represented on the stage, it’s more likely that we may want to consume this music and more likely that we may feel like we want to be there and belong there. If we want to see diversity in our audiences, and thus reflect our diverse societies, we first need to showcase it on our stages.

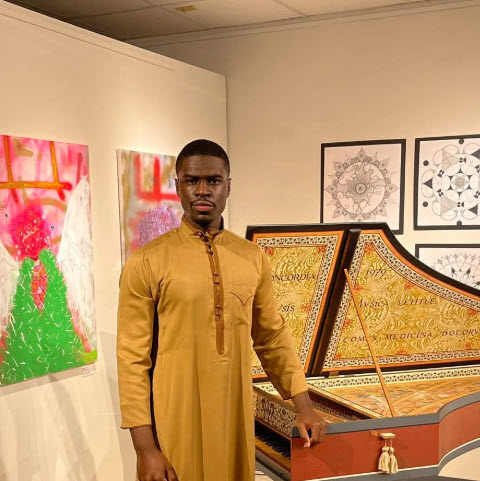

Ensemble Obiora is exemplary in this work, and they are changing the look of the music scene as Canada’s first classical music ensemble composed mostly of professional musicians from diverse cultural backgrounds. Rooted on the principles of DDD — diversity, discovery, dissemination — their mission is to promote musicians from different cultural backgrounds to increase representation in classical music, and to program unfamiliar works by composers of color whose contributions have gone unnoticed.

Ensemble Obiora was founded in 2021 by Allison Migeon and Brandyn Lewis, who noted the lack of diversity represented in Canadian classical music, both on and off stage. When they learned of groups such as Chineke! Orchestra and the Sphinx Organization, they decided they could do something about it, too. Their goals are “to bring a new and diverse voice to classical music in Canada, to create a sense of belonging in underrepresented communities, and to inspire the next generation of classical musicians.”

‘On the community’s own terms’

Diversifying programs and performers without the groundwork and sensitivity toward best practices, however, can come with issues such as cultural appropriation and tokenism, among other complications. When a collaborator from a diverse background is not given artistic agency or a leadership role in a program of diverse music, and their presence is only used to legitimize an existing program, it is tokenism. Infusion Baroque’s Amawat says she’d love to see more musicians and ensembles engaging in longer-term initiatives with artists outside the typical early-music scene: “By doing this, we can avoid tokenism and truly expand the field in a meaningful way.”

With regards to equity and access, the path is also not as clear cut. There are many variables, especially funding. Last season Infusion Baroque implemented a pay-what-you-can pricing system to make their concerts accessible to all audiences. “We found this model to be pretty successful last year,” says Amawat, “and we will continue to use it while directing our marketing strategies to a broader demographic as well.”

When established ensembles (especially those that are white-led) recognize their historical privileges, it should help guide them to give back to their community and, by necessity, to consider how they allocate their resources. This was the case of Ensemble Caprice.

In the summer of 2022, they asked me to design, direct, and manage a project with IDEA values in mind that would contribute back to the community. I was given total autonomy to launch ClassiqueInclusif: a project that aims to elevate and celebrate diversity in classical music by presenting free concerts that are curated and in collaboration with performers, composers, and community members from historically underrepresented minorities in the greater Montreal area.

ClassiqueInclusif concerts are framed on the theme “Our musics, Our stories.” They celebrate the rich cultures of the communities represented. They share tales of immigration, identity, and belonging through music, poetry, and storytelling.

The basic idea is to take classical music from the concert halls and bring it into the communities, but on the community’s own terms: music in their language, music they identify with, music that includes them in the artistic process by enabling them to tell their own stories. Colombian Anthropologist Doris Castellanos, with whom we worked in our most recent concerts, says that “telling our immigration stories gives us a place and, above all, makes us visible to others; it gives us a sense of belonging. For migrant bodies, belonging is a conquest that embraces the soul.”

ClassiqueInclusif aims to build long-lasting relationships by centering, each year, on a specific, traditionally underrepresented community in classical music. We engage the same group of musicians through the year, and partner with local institutions that help and gather these communities. Over the past year, we focused on the Latino-American immigrant and refugee community in Montreal, and performed four concerts of Baroque and traditional Latin American villancicos as well as Baroque, Classical and traditional music that celebrates the Latin American identity, all with period instruments.

We are preparing the new season, focusing on Arab and West Asian refugees, with Lebanese-Palestinian tenor Haitham Haidar as co-artistic director.

But there is no one-size-fits-all fix; If we want a more inclusive, more diverse, more equitable, and more accessible field of early music, we all need to work together. We start by recognizing our privileges and confronting our own biases and prejudices.

But why does the field need to change? I could get out my post-colonial theory texts, talk about perceived supremacies of ontologies, and so on. But the answer I go for is rooted in empathy: because we all deserve to be here, we all deserve to feel included and welcomed, represented and respected, and we all deserve to have equal access to music.

Karin Cuéllar Rendón is a Bolivian historical violinist and researcher currently residing in Montreal. She serves as co-chair of EMA’s IDEA Task Force and is a Ph.D. candidate in musicology at McGill University.