by Aaron Keebaugh

Published December 12, 2022

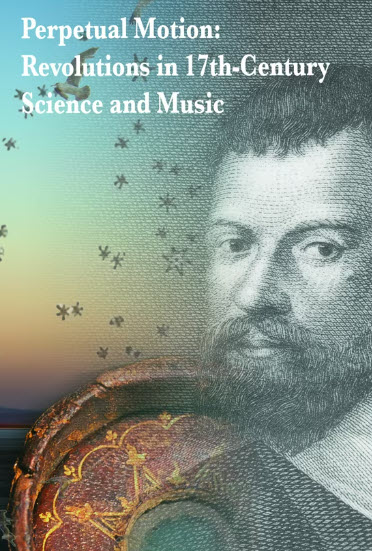

Perpetual Motion: Developments in 17th Century Science and Music [DVD]. Music from Galileo’s World [CD]. Galileo’s Daughters. Sarah Pillow and Marc Wagnon, producers. Buckyball Music.

Even during house arrest, Galileo Galilei prayed to God for guidance and salvation. Steadfast faith served as his anchor, even enhancing the rapture he felt over making his scientific discoveries. The mysteries of the universe and religious reverence, much of it played out through contemporary music, flourished together in a world still on the brink of new human understanding.

Viewing Galileo’s scientific advancements through contemporary ideas of religion and the arts forms the crux of this new multimedia project by the New York-based ensemble Galileo’s Daughters. Yet while music and narrative combine for fresh insights, wayward video images and prerecorded sounds remind that less can be more.

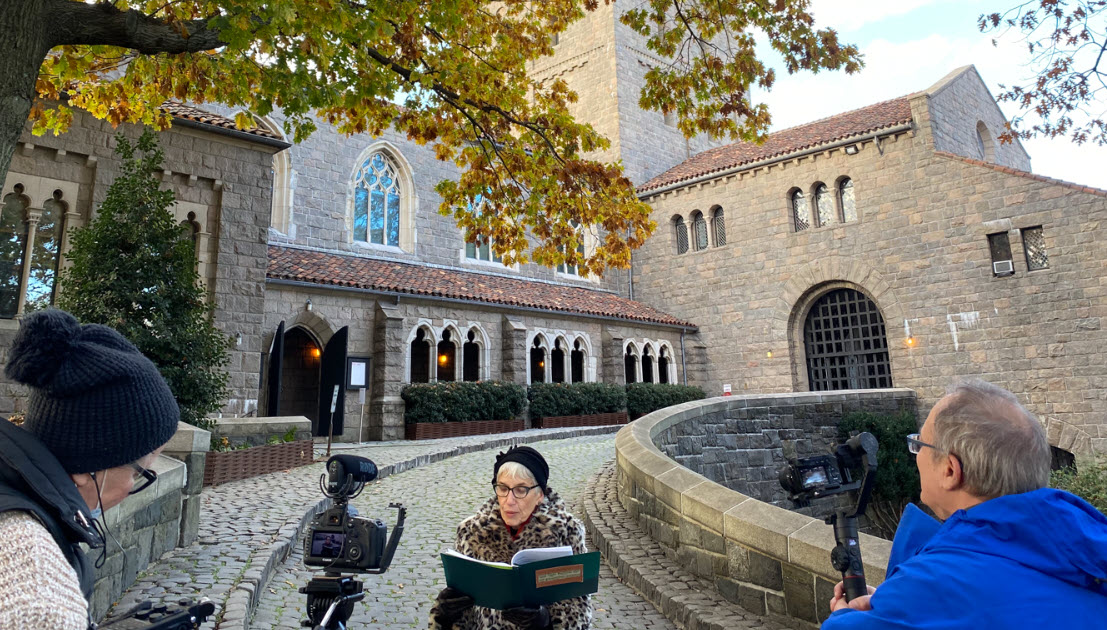

Galileo’s Daughters created this program for home release after the COVID pandemic shuttered their live recitals. It explores arias and songs by Barbara Strozzi, Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana, and Claudio Monteverdi, and others alongside short works for viola da gamba, lute, and theorbo. The narration, written and delivered by Dava Sobel, a Pulitzer Prize finalist for the historical memoir Galileo’s Daughters, threads it all together with details from Galileo’s life and times.

It seems an odd mix on the surface, but Sobel guides us through many fascinating connections. She focuses attention on Galileo’s father, the composer and theorist Vincenzo Galilei, who played a crucial role in the musical developments of the early Baroque. Among them was scientific tuning, which Sobel thoughtfully ties to the ancient Greek idea of the Music of the Spheres. Sobel reveals that physicist Johannes Kepler used musical notation to create scales for each planet from Mercury through Saturn (which has the lowest and slowest musical motion).

Considering these associations, Cesare Negri’s Catena d’Amor is truly illuminating, flowing here with expressive freedom by lutenist Ronn McFarlane. Short works by Bartolomeo Tromboncino and Giovanni di Palestrina (that papa Vincenzo included in his treatises) abound with lyrical and terpsichorean qualities.

Sobel also draws parallels between scientific developments and the musical theories that brought opera into the Western world. Antonio Archilei’s “Dalle piu alte sfere” brings the combination of speech and music into sharp relief. Sarah Pillow’s soft soprano relays solace as well as turbulence—a glimpse, perhaps, of the universe of human emotion. Accompanying images of galaxies and stars in swift motion remind viewers that nature is just as mercurial.

Pillow also sings Giulio Caccini’s “Tutto’l di piango” with gentle presence and sensitivity. Vocal flourishes nurture unyielding grief, as they do in Monteverdi’s “Lamento d’Arianna.”

Yet other selections connect little with the themes. Francesco Cavalli’s “Dalle gelose mie” from the opera La Calisto, which tells of passion and inner turmoil, follows narration about Greek mythology and ancient ideas of the heavenly bodies. The same holds for Barbara Strozzi’s “Il Romeo,” a well-performed if arbitrarily placed aria about love and the dark emotions that lie in its wake.

Some videography feels as though it was placed merely to fill space. Pictures of stars, nebulas, and Jupiter’s moons are indeed eye-catching. But during the operatic excerpts, we find pictures of rivers, mountains, and, for some reason, a solitary figure walking in the desert. The music by itself, as corollary to the narrative, would have been enough.

Yet the performances exploring religious themes are simply gorgeous. Pillow’s soprano floats and dances in Monteverdi’s “Laudate Dominum,” conveying both divine comfort and devotional bliss. Henry Purcell’s An Evening Hymn—presented in reference to Isaac Newton, who had brought together the thought of Kepler and Galileo—concludes the program in warm reverence.

The performances on the accompanying CD, Music from Galileo’s World, are likewise superb. Pillow’s upper register sets aflame the burning desire for the divine in Isabella Leonarda’s “Care Plage.” In Chiara Margarita Cozzolani’s “O Maria tu dulcis,” the ensemble lines caress the ear with delicate harmonies. Florid melismas and trills tease out the flair of Vizzana’s “Sonet vox tua.”

But here, too, the extra sonic fluff is unnecessary. Each track opens, curiously, with sounds from the natural world. Rushing wind introduces Caccini’s “Tutto’l di piango” and Monteverdi’s “Lamento d’Adrianna.” A thunderstorm sets the scene for Cavalli’s “Dalle gelose mie.” Maybe it suggests the text’s expression of angst? Mostly it’s just corny.

Fortunately, the performances assuage any annoyance. Pillow tosses off phrases with ever greater urgency in Rosa Giacinta Badalla’s “Non plangete,” a personal testament of faith and the struggle to maintain it.

The instrumentalists also generate a soulful swagger. The slight grain of Mary Anne Ballard’s viola da gamba tips the lines of Jacques Arcadelt’s “O felice occhi miei” towards darkness, while lutenist McFarlane offers supple support. Theorbist Daniel Swenberg plays Giovanni Kapsberger’s Toccata arpeggiata with just enough rubato to probe the depths. Exceptional performances, these musicians reveal, are all this music really needs.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in Danvers, Mass.