by Kyle MacMillan

Published October 23, 2022

A William Byrd Festival, at Northwestern, surveys the Renaissance composer 400 years later

Like many a Renaissance composer, William Byrd does not enjoy the kind of recognition claimed by heroes of the Baroque. But Byrd’s profile is likely to get a significant boost in 2023, when the early-music world commemorates the 400th anniversary of his death. The celebrations have already started, with new recordings, festivals, and creative concert programming.

Getting an early start, Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music, in Evanston, Illinois, is presenting the William Byrd Festival this week, October 27-30.

It includes three concerts offering of an overview of his output—voices, viols, virginals, and more. There’s also an open rehearsal and, kicking off the festival, a lecture with the delicious title “The Lives of Singers in Tudor England: What Could Possibly Go Wrong?” by musicologist Kerry McCarthy, author of an award-winning 2013 biography of the composer.

Festival co-organizer, Stephen Alltop, on the Northwestern faculty, points to one of many highlights: the participation of six professional musicians from the Chicago area who perform on the viol or viola da gamba, a stringed instrument popular in the Renaissance and into the Baroque era. Though they slightly resembles instruments in the now-familiar violin family, it is different in key respects, including its five to seven strings (vs. four strings in the violin family) and for its underhand bow grip.

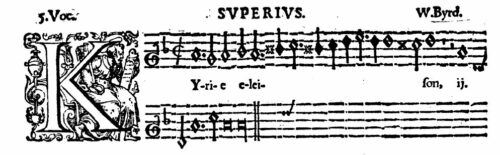

For the Voices and Viols concert, explains tenor Bradyn Debysingh, a Northwestern graduate student planning a career in early music, “it’s very rare to get to perform this music with six viol players!” The repertoire includes the Mass for Five Voices, “Christ Rising Again,” Ave verum corpus, and Miserere mei Deus, plus consort music for viols.

“To actually perform this music as it was intended to be performed, in an intimate setting, is such a delight and special opportunity,” enthuses tenor Debysingh.

Unlike a noted Renaissance composer such as Tomás Luis de Victoria, a Spanish contemporary who wrote music primarily for church choirs, the Englishman Byrd had a much broader reach, composing works in nearly all the genres of his time. These include keyboard and other instrumental works, sacred music, and secular songs—in all, about 470 compositions. “What Victoria did was incredibly, amazingly good, but he only did one thing,” said musicologist and singer McCarthy, based in Portland, Oregon. “Byrd was incredibly versatile. If we only had his instrumental music, if we only had his keyboard music, he’d still be known as a great composer.”

‘Eight reasons why everyone should learn to sing’

Byrd’s first known post was organist and master of the choristers at the Lincoln Cathedral from 1563 through 1572, when he left for the more important appointment as Gentleman of the Royal Chapel, serving Queen Elizabeth I. Although she was the titular head of the Church of England, Byrd wrote surprisingly little Anglican church music. He began associating with Catholicism in the 1570s and wrote more music for that religion, which had to be practiced covertly, as Catholicism was essentially banned, often violently repressed, in England.

There is much that is not known about Byrd. But he provided valuable glimpses into his enthusiasm for music and his thinking and personality in the prefaces, dedications, and introductions to his publications. “Pretty much every book of his music that he printed,” McCarthy says, “has this wonderful first-person essay at the beginning, and, of course, a lot it is flattering to the patron who paid for it. But then he often turns to the reader, turns to the musician, and says, ‘this is what it was like to compose these pieces, and this is what you might want to do with them.’” His first songbook from 1588 has a famous list of eight reasons why everyone should learn how to sing.

During Byrd’s lifetime, his music was slightly performed in northern Europe, but, in general, it was little heard outside of England. That is still true in many ways today. Because most of the texts for his works are in English, the bulk of the performances of his works take place in English-speaking countries, where the language makes it most easily accessible. “Maybe that will change with the anniversary,” McCarthy says. “The big 400th year might get more people playing and singing his music.”

Besides a short matinee concert on October 30 highlighting the virginal, a keyboard instrument in the harpsichord family, the Northwestern festival encompasses two main performances starting October 28 with a concert featuring the 24-voice Bienen Contemporary/Early Vocal Ensemble. It is titled The Angelic Byrd and features works relating in some way to angels, including selections from the Byrd songbook, Psalms, sonnets, and songs of sadness and pietie (1588).

At the main October 30 concert, Viols and Voices, Alltop conductor and plays keyboards and will lead Northwestern’s 33-voice Alice Millar Chapel Choir, and the six-piece viol consort.

“I’ve been playing the viol for 20 years, and, so doing that, you end up playing a lot of Byrd because he wrote lots of different styles for viol. We as viol players definitely celebrate him as a composer,” says Kate Shuldiner, one of the viol players. The performance takes place in the Millar Chapel, a 700-seat contemporary Gothic structure on Northwestern’s campus. “It’s a glorious, reverberant space ideal for the soft and intimate sound of the viols,” Alltop offers. “I think it will be quite magical.”

The program’s centerpiece is Byrd’s Mass for Five Voices, which has two tenor parts that give it an Italian flavor and what McCarthy called “such a big, rich sound.” Unlike, say, Palestrina, another Renaissance giant, who wrote some 100 masses, Byrd only produced three. “They’re just absolutely perfect works,” McCarthy says. “You can tell that he put so much care into each one of those.”

The program’s centerpiece is Byrd’s Mass for Five Voices, which has two tenor parts that give it an Italian flavor and what McCarthy called “such a big, rich sound.” Unlike, say, Palestrina, another Renaissance giant, who wrote some 100 masses, Byrd only produced three. “They’re just absolutely perfect works,” McCarthy says. “You can tell that he put so much care into each one of those.”

Written for England’s underground Catholic community, she says, the works are “not too long, not too loud, and not too showy.”

The rest of the program is devoted to pieces showcasing the viols alone and consort songs, a distinctly English form of the late 16th and early 17th centuries that features a solo voice or group of voices accompanied by an instrumental ensemble, the viols in this case. Shuldiner is especially looking forward to the consort songs, which she rarely gets a chance to perform. “When you work with singers in general but especially in these settings,” she said, “you have to think about you bow a little differently and how you shape phrases. And really think about the breaths, and where they [the singers] are taking breaths.”

This week’s Byrd event is under the auspices of the Evelyn Dunbar Memorial Early Music Festival, which was established in 1996 by Ruth Dunbar Davee and her husband, Ken M. Davee, and named in memory of Ruth’s sister. Past offerings, with a similar format, have centered on such themes as Monteverdi’s Vespers, Haydn’s The Creation, and the early career of Handel. “These festivals are educational gold mines for our students,” Alltop says.

The sorts of events are, of course, equally valuable for faculty members. Alltop consulted with McCarthy about the works he is performing as part of the festival, and more such conversations will naturally come during her visit. “The ability to work directly with leading scholars on the music and they know so well,” says Alltop, “enhances our knowledge of performance practice. That’s not just for the students, that’s for all of us, including on the faculty. And I really love that.”

Kyle MacMillan, a regular contributor to Early Music America, served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as The Wall Street Journal, Opera News, and Chamber Music.