by Parker Ramsay

Published August 29, 2022

Recently, a few friends and I planned an evening of chamber music. Put yourself in my position for just a moment.

Chamber music for the harp is normally pretty easy to categorize. The collaborative harp repertoire really got going with the French Impressionists (notably Debussy, Ravel) and their successors around the globe (Britten, Takemitsu, Carter). In short, we’ve no written scores of substantial repertoire before about 1900—with one glaring exception, which sits in Volume XXI of Musica Brittanica. Open the collected works of William Lawes (1602-1645), and you’ll find a set of pieces known as the Harp Consorts, scored for violin, viol, theorbo, and harp.

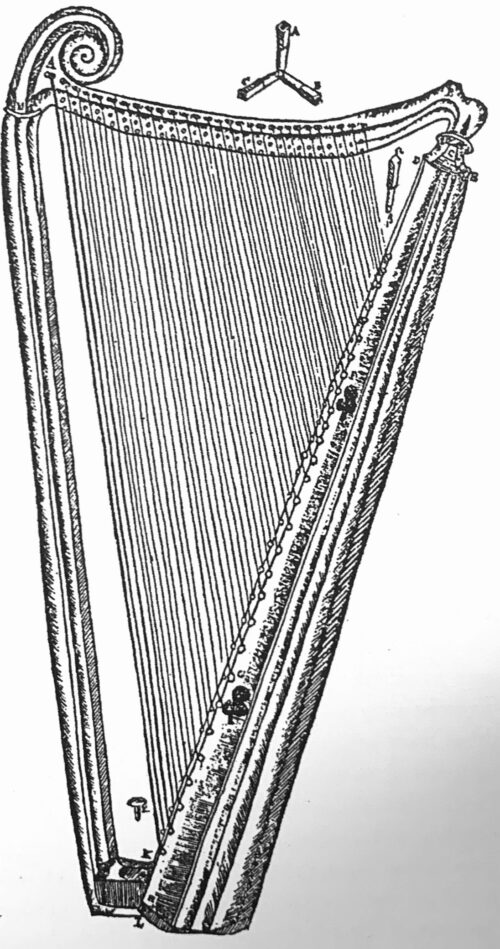

Lawes’ harp parts are florid and virtuosic and, most interestingly, fairly chromatic—remarkable on the surface, since harp with pedals did not exist until the 18th century. Lawes’ writing likely required multiple rows of strings to navigate all this chromaticism with ease.

You’ve found the scores, ordered performer parts from PRB Productions, and your three historically informed friends are holding a date in their calendars.

Good to go, right? No.

Before you get started, you have to figure out what type of harp you’re going to use.

It’s been established that a gut-strung harp of three rows was introduced to the court of Charles I by John le Flelle (as reported by Marin Mersenne in his Harmonie Universelle), who was sworn in “as his Majesty’s servainte and musician for the harp” in 1629. (Thus preceding William Lawes’ appointment as a court musician in 1635). Dr. Cheryl Ann Fulton’s research in the PRB edition makes a convincing argument that the Francophilia court of Charles I would likely have opted to use just such a gut-strung, three-row harp.

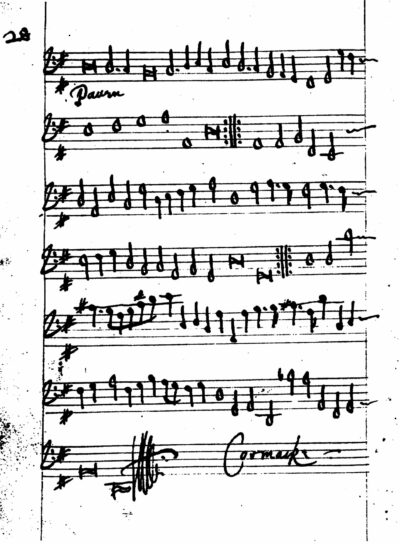

But other harps had a longer and more established presence in the court. A harpist by the name of Cormack Dermode (or MacDermott) was employed in the service of Elizabeth I in 1605, after having been hired by Robert Cecil in the diplomatic mission from Cork as early as 1602/3. In all likelihood, Dermode performed on a smaller harp with wire strings, akin to the cláirseach, for which he himself composed consorts with the same instrumentation later used by Lawes’. (The connection between the two is strengthened by the fact that Lawes’ Harp Consort No. 9 contains set divisions on a pavan by Dermode.) And in 1620, the Treasurer of the Chamber hired another harpist, William Evans, who was later described as being taught the Irish harp from 1618 to 1628. Again, this is before of Lawes’ appointment to the court.

So your harp will be either Anglo-continental or Irish, although please note that these two instruments sound incredibly different.

While the gut-strung harp has great clarity and presence, it sounds similar to a theorbo. Mersenne said of John le Flelle, “who plays this harp, are not sure whether to prefer it to the sound of the lute.” Perhaps what is preferable is the bell-like quality of the wire-strung harp, which doesn’t sound like any other instrument. Francis Bacon noted that “some Consorts of Instruments are sweeter than others (a thing not sufficiently yet observed;) as the Irish-Harp and Base-Vial agree well.” You get the sense that maybe people back then preferred one instrument to the other. Should we today drop thoughts of what we ought to do and, instead, ask ourselves the most treacherous of all questions in historically informed performance: What do we prefer?

And there’s more. Among harpists, it’s difficult to have a calm conversation about instrumentation in the Harp Consorts because of these instruments’ potency and continual use in nationalist movements. Just as the cláirseach has retained its stature as Ireland’s national instrument, le Flelle’s triple-strung harp was adopted by Welsh harpers in the later 17th century and is now the national instrument of Wales. When one inserts one of these two instruments into a consort performance (almost always framed as “English” music), the boundaries shift and the works inevitably become illustrations of the nature of music-making and the historical grafting of national identities. As unlikely as it sounds, the complications inherent in a little set of consort pieces from Stuart England somehow seem to foreshadow all sorts of political upheavals across Britain and Ireland.

Still, I wonder how relevant these standards are when we dig a little deeper into history. For instance, scholar Peter Holman makes a big deal about how Cormack Dermode was an “Irishman,” but investigation paints a more complicated picture. Dermode (who was, in all likelihood, a Protestant) got his start working in the inner sanctum of Robert Cecil, a relatively merciful arbiter between Irish rebels and Elizabeth I in the Nine Years War, which was a battle for Irish autonomy and Roman Catholic emancipation. (Cecil was also the famed uncoverer of the Gunpowder Plot, in which he himself may have been an agent provocateur.) Dermode’s continued employment under Cecil stretched well into the 1610s, by which point he was living in the fashionable London area of St. Martin-In-The Fields and working as a court musician until his death in 1618.

Dermode’s example is complex, but not unusual. Protestant though he may have been, it’s hard to firmly establish the extent of his Gaelicization or adoption of indigenous modes of cultural expression—we’re not even positive whether his family were descended from settlers who arrived anywhere between the 13th and 16th Centuries. In recent weeks, I’ve become particularly fond of the historian Sean Connolly, whose account of fighters at the Battle of Knockdoe in 1504 reports, “But there would also have been others, particularly from the outer Pale, whose Gaelic speech and dress belied their English surnames, as well as Irishmen who had to a greater or lesser degree conformed to English manners and appearance.” Fast forward a century or so, and Dermode appears to be a testament to a similar phenomenon.

In sum: No easy answer. Cheryl Ann Fulton concedes in her research that some consorts may have been intended for an Irish harp, and others for the gut-strung harp. (That is, they can be seen as works that look forward, from a developmental standpoint). A contrary view is that the Harp Consorts testify to a precedent of mixed consort practices with the harp which emanated from Ireland. In my mind, the best solution would be to dispense with loaded terms “Irish,” “Welsh” or “Anglo-Continental” and stick to the basics like “gut strung” or “wire strung.” Voltaire said that history is a pack of tricks the historians play on the dead. No matter how you choose your instrument for the Harp Consorts, you’re doing to have to navigate seas muddied by our interpretations of the past.

Parker Ramsay, earlier this year, premiered The Street, a concert-length solo for harp by Nico Muhly and Alice Goodman. His season includes a residency at IRCAM, working with composer Josh Levine on a new work for harp and electronics. While serving as organ scholar at King’s College, Cambridge, he earned his undergraduate degree in history, and later pursued graduate studies in historical performance at Oberlin and modern harp at Juilliard.