by Saraswathi Shukla

Published June 12, 2023

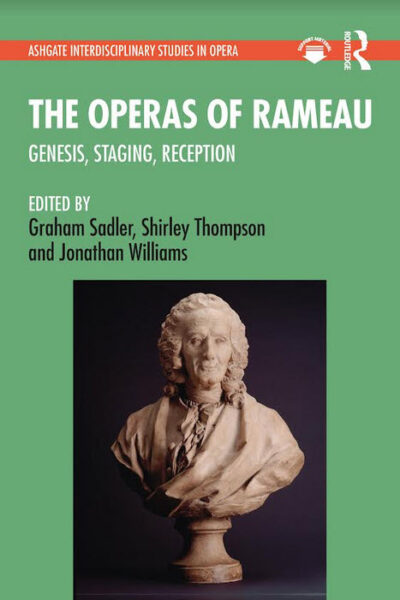

The Operas of Rameau: Genesis, Staging, Reception. Edited by Graham Sadler, Shirley Thompson, and Jonathan Williams. Routledge. 2021. 310 pages.

Two conferences commemorating the 250th anniversary of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s death took place in 2014: one in Paris, another at St. Hilda’s College, Oxford. These Oxford proceedings are an exceptional addition to the literature on Rameau’s operas for researchers, musicians, and producers alike, made more significant by the fact that, although Rameau studies flourish in France, French musicologists’ work infrequently appears in English. (The proceedings from Paris, Rameau, entre art et science, were published in a bilingual edition in 2016).

Curated by three experts on Rameau’s music — Graham Sadler, Shirley Thompson, and Jonathan Williams — The Operas of Rameau presents cutting-edge research from the United Kingdom, United States, France, and Italy. The articles are arranged thematically in four groups: Factions and Rivalries; Libretti; Borrowings and Creative Renewal; Production, Performance and Criticism.

Curated by three experts on Rameau’s music — Graham Sadler, Shirley Thompson, and Jonathan Williams — The Operas of Rameau presents cutting-edge research from the United Kingdom, United States, France, and Italy. The articles are arranged thematically in four groups: Factions and Rivalries; Libretti; Borrowings and Creative Renewal; Production, Performance and Criticism.

Part I examines the tendency in studies of French Baroque music to dichotomize and rely on the frameworks provided by aesthetic debates between, for instance, Lully and Rameau, Rameau and Rousseau, Rameau and Mondonville, the Opéra-Comique and the Académie royale. The contributors present new sources and perspectives on how this reliance has led to misrepresentations and misinterpretations of the nature of these tensions and their chronology, but the authors sometimes focus more on these binaries than on their sources, which are evocative and often unexpected, but occasionally underexplored.

Francesca Pagani beautifully demonstrates how Jean Galli de Bibiena, in his Mémoires (1735), saw the influence of philosophers and artists like Newton, Le Brun, and Da Vinci on Rameau’s music. Rather than exploring these comparisons, she focuses on Bibiena’s significance as a rare supporter of Rameau’s Italian roots. Benoît Dratwicki and Françoise Escande argue that the generation between Lully and Rameau was excised from histories of French music as early as the 1760s, instead of developing their perceptive observations about the subtle distinctions between the composers, the institutions that supported them, and their compositional styles. Thierry Favier masterfully resituates Mondonville in the history of French music by revisiting music histories of the period and presenting a holistic study of musical institutions.

In Part II Roger Savage makes the striking observation that, out of a survey of over 120 librettos, the quality of generosity (a Cartesian influence) plays a pivotal role in only three: Rameau’s “Le Turc généreux” (an act from the opera Les Indes galantes), “L’histoire” (from Les Fêtes de Polymnie), and Anacréon (1754), each presenting love triangles that are only resolved by an act of generosity by the most powerful character. Savage proposes a pastiche uniting these three and even provides a libretto (!) called Le Triomphe de la générosité, ou, Fragments de Monsieur Rameau.

Marie Demeilliez tells the story of Linus, an unfinished tragédie en musique that would have contained the only known instance of two successive storm scenes. Recounting the personnel problems that eventually sank the production, Demeilliez brings Rameau to life as he attempted and failed to negotiate his compensation and work conditions with his patrons. Thomas Soury reconsiders the unproven attributions of the librettos for Io, Zéphire, and Nélée et Mirthis by comparing their plots to those of Rameau’s most famous librettist, Louis de Cahusac.

Seeking to undo Rameau’s reputation as “an absent-minded old theorist, obsessed with harmonic combinations” — for most of us, he is a lively composer — Raphaëlle Legrand links Rameau to a literary society known for producing erotic literature, which is not surprising given his collaborations with the Parisian fair theaters. Yet her article incomprehensibly rests on a comparison of Rameau to Crébillon fils, a claim that the sexually charged wordplay is specifically characteristic of libertine novels, and an interpretation of the pastoral as a Louis XV-era mode. It suffers from bibliographical omissions in literary studies (e.g. Mikhail Bakhtin, Marc Fumaroli); she cites Ovid, Horace, and Virgil as sources of mythological information but not as literary influences; and there is no consideration of studies of Italian and English opera and theater with similar themes.

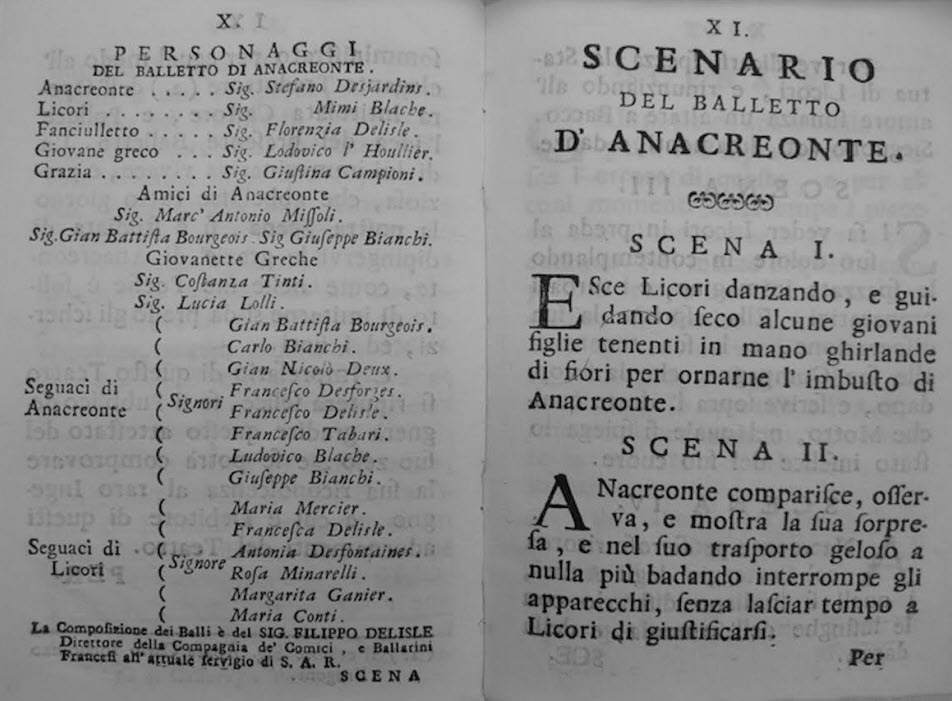

Reception studies and studies of borrowings and arrangements always illuminate fascinating connections. Graham Sadler identifies several citations in Rameau’s 1757 Anacréon from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, which was tremendously popular in France. He insightfully remarks that Rameau, who, in his 70s, was a symbol of French conservatism in the face of new Italian trends, nonetheless turned to these concertos for inspiration. Margaret Butler presents a powerful example of how French and Italian operatic traditions collided head-on, when Rameau’s brother-in-law, Jacques-Simon Mangot, drastically adapted several of Rameau’s operas, including Anacreonte for the opera in Parma in the 1750s.

J. Arnold considers the political implications of a Castor et Pollux first produced by Pierre-Joseph Candeille in 1791 and intermittently reprised until 1817 (after Napoleon’s defeat). This setting united Gossec’s instrumentation and Gluckian aesthetics with six pieces from Rameau’s original. Thomas Leconte discusses a Messe des morts with borrowed music from Mondonville’s Les fêtes de Paphos (1758) and Rameau’s Castor et Pollux (1754).

The last section of the volume contains stunning reflections on production, theatricality, timing, and pacing. Laura Naudeix revisits the question of why “Les Sauvages” was added so late to Les Indes galantes by considering the Académie royale’s preoccupations as a business with financial investments and a need for audience loyalty: overlapping negotiations, particularly with the dancers, likely necessitated the addition of this well-known piece to the production.

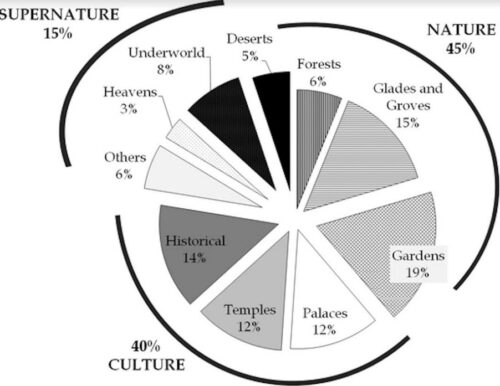

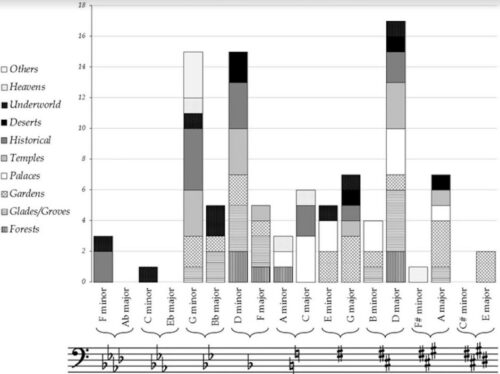

Lois Rosow analyzes three recent productions of works by Lully and Rameau (by Benjamin Lazar, Pierre Audi, and Jean-Marie Villégier) in the context of dramaturgical texts written by Rameau’s contemporaries. When are scene changes done with an open curtain and when are they accompanied by entr’acte music? And how do productions balance dramatic continuity and interruption at these pivotal moments? Michel-Rémy Trotier finds that Rameau was less inclined to associate specific keys with supernatural, natural, or cultural settings than he was to accompany changes of setting and décor by relative modulations sharpwards or flatwards.

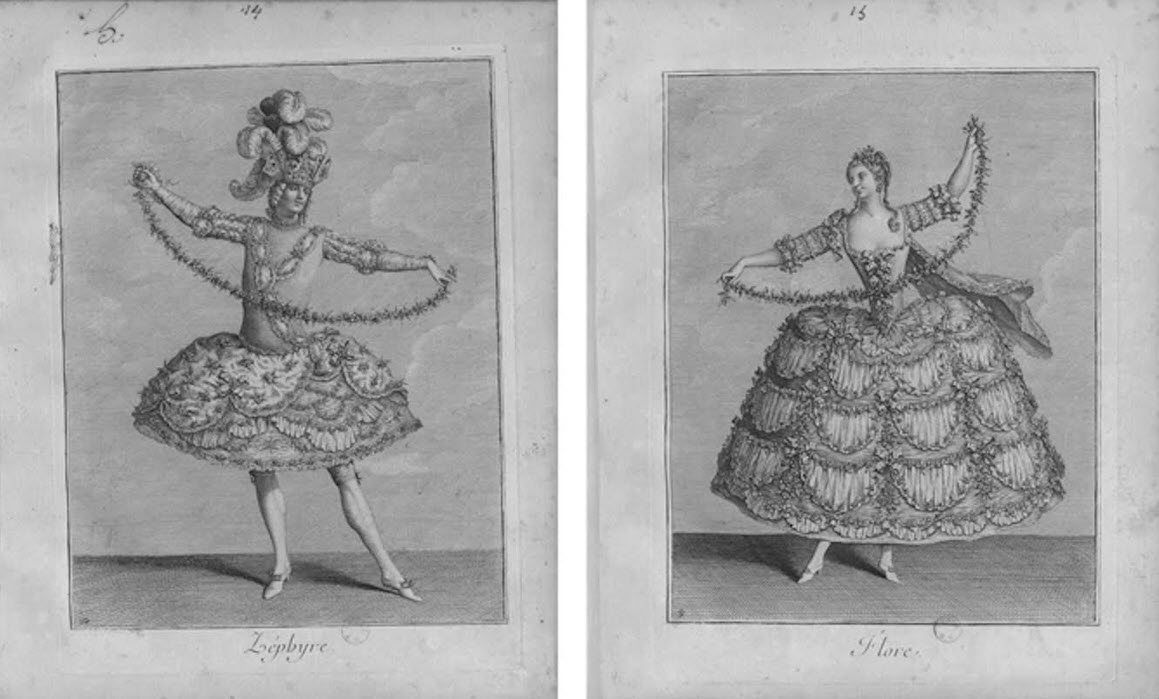

Thomas Green identifies a shift in the kinds of reviews found in the Mercure de France by noting Madame de Pompadour’s likely influence on the possible authors. A highlight is Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Hubert Hazebroucq’s collaboration as they construct a kind of guide to choreographing Rameau’s works (with online video examples). Beginning with parts of the unpublished ballet Zéphire, which contains annotations by Rameau but was probably never performed, they draw one-to-one correlations between gestures and steps and specific instrumentations, types of dramatic development, gendered characters (often ambiguously defined), and rhythmic motifs. By outlining an approach to reconstructing choreography, they provide the tools for dancers, musicians, and producers to make similar decisions.

Alongside these varied essays on Rameau, the book offers several valuable practical resources: a checklist of operas accompanied by information about their genre, the number of acts/entrées, librettist, premiere, first publication, and subsequent recent editions; a discography of Rameau’s operas with an essay by Patrick Florentin; online video examples; and appendices to the articles when necessary. The authors build upon one another’s work, presenting a tightly woven, multilayered dialogue within each section and across the entire book. This is an essential for anyone interested in French Baroque opera.

Saraswathi Shukla received her PhD in Musicology from UC Berkeley and an AB in History from Princeton University and is currently a lecturer and researcher at the Université de Lorraine. She is the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards, including the Alvin H. Johnson AMS 50, the Georges Lurcy Fellowship, the Chateaubriand Fellowship, a DAAD Study Scholarship, and the Irene Alm Memorial Prize.