(Photo by Chris Christodoulou, courtesy of Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras)

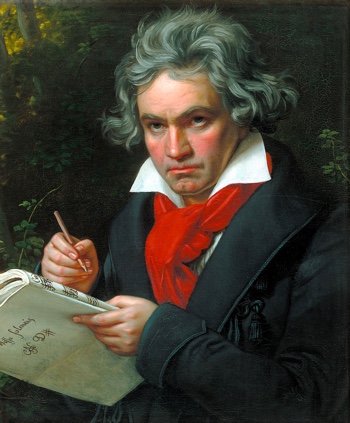

To say that Ludwig van Beethoven’s nine symphonies are regularly heard on orchestra programs worldwide almost qualifies as an understatement. At least a couple can be found every year among the 20 most performed works by orchestras in the United States. And in 2003-04, to cite one season, the Symphony No. 5 topped the list, according to a report prepared by the League of American Orchestras.

Given the ubiquitousness and enormous popularity of the nine symphonies, an obvious question is whether they need yet more attention. English conductor John Eliot Gardiner asserts the answer is an emphatic “Yes!” Despite decades of performances and reams of journal articles, he believes there is still more to be learned from and appreciated about these amazing works, which were premiered from 1800 through 1824 and span nearly Beethoven’s entire professional career. The key, the conductor noted, is to present them in a manner as close as possible to what the composer envisioned.

“Why should we bother?” Gardiner said in an interview for Early Music America. “Because Beethoven has been monumentalized so much in the late 19th century and all through the 20th century that maybe we’ve lost the impact and the freshness of those symphonies and how they must have occurred to people like Berlioz and Wagner.”

To mark the 250th anniversary this year of Beethoven’s birth, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir — both period-style ensembles that Gardiner founded — will present all of Beethoven’s symphonies (plus a few related works or excerpts) during five sets of concerts from February through June in Barcelona, New York, Chicago, London, and Athens. The New York performances will take place Feb. 19 through Feb. 24 at Carnegie Hall, and the Chicago ones are set for Feb. 27 through March 3 at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance.

Presenting the symphonies in several days, rather than across a concert season, as the set is often heard, allows listeners to hear the “incredible progression” that takes place in a concentrated and revealing way, Gardiner said. He has done such focused cycles a few times in places like Japan and California, and he found them to be a success. “It brings an incredible kind of supercharged excitement from evening to evening.”

Gardiner’s history with the symphonies goes back to his student days in Paris in 1967-68 with the celebrated pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. But he didn’t conduct any of them until he was in his 30s, and those performances were with conventional symphony orchestras playing modern instruments. In 1989, he formed the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique so that he could perform in particular the works of Beethoven but also those of the composer’s successors, like Berlioz and Schumann, in a historically informed manner. “They’re mountains, they are a mountain range that you have to climb as a musician, as a conductor,” he said of Beethoven’s symphonies. “It’s just non-negotiable. You have to do it. The question is how and with what forces, what equipment.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, ensembles like the Academy of Ancient Music in England upended the classical-music world with a revolutionary approach to the music of the Baroque era — roughly 1600 to 1750 — and earlier. They employed period instruments and performance practices they uncovered through extensive historical research, work that also turned up a treasure trove of forgotten or nearly forgotten composers and compositions. Soon, however, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and other groups began to apply these approaches to the more familiar music of the Romantic era and early 20th century.

For Gardiner, the starting point in interpreting Beethoven’s symphonies is realizing that the composer did not hear the last six or seven of them because of his tragic, much-discussed hearing loss. “Therefore, he created and invented, in a way, an ideal orchestra that he was never able to witness,” he said, “and that is a terrible affliction for a composer. And the question in my mind always was: To what extent can we recover, can we get close at least to that imaginary sound world that he had so vividly ringing in his ears? He made such incredible, modern strides forward into modernity. Is it a mirage? It is something that one can hope for but actually never grasp?”

He believes musicians today can “grasp” that sound world if they set about it in the right way. That means extensively researching how the symphonies were performed in Beethoven’s time and then endeavoring to re-create the approach. One useful model is the documentation of what Gardiner called the first “really well-rehearsed” performances of the nine symphonies soon after François Antoine Habeneck became founding director of the Paris-based Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire in 1828 — a year after Beethoven’s death. Significant contemporaneous musicians such as Berlioz and Wagner left insightful accounts about the instruments that were used and the sounds that were produced.

Although musical instruments that were developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries provide more technically secure performances and project better in large halls, Gardiner said, a case can be made that they can actually mask some of the “originality and fire” of Beethoven’s imaginary orchestra. “If I listen to recordings of the great conductors of the 20th century, starting with Furtwangler, Toscanini, and Klemperer, you feel that they are in a way sculptors sculpting clay that has been formed by Wagner, Gustav Mahler, and late 19th-century composers rather than the raw clay that Beethoven molded his symphonies with.”

Gardiner asserts that audiences who attend his ensembles’ upcoming presentations of the Beethoven symphonies will hear more of the “inner conversations” that take place within the works, as well as a wider palette of colors. The period wind instruments have more distinctive voices than those in a modern orchestra, and the stopped and open sounds produced by French horns of the composer’s era offer what Gardiner calls a different “plangency” to his writing for the instrument. In addition, the hard mallets and skin versus plastic heads on the historical timpani give the symphonies a more percussive definition than their modern counterparts can provide.

Perhaps most important, Gardiner said, is what happens when the needle swings into the red zone in terms of dynamics and force during a Beethoven performance. With a modern orchestra, he said, that needle can only go so far without the sound becoming overbearing and turning into what he called an “unholy mess.” But because period instruments are lighter in timbre and power, they can be pushed to their maximums at both ends of the dynamic spectrum — the loudest fortissimos and softest pianissimos. “And there is a much more visceral excitement that comes through as a result,” he said.

One of the most controversial aspects of Beethoven’s symphonies are the metronome markings he provided for them, which many interpreters past and present have disregarded in part because the indications were deemed infeasibly fast. For his groundbreaking period-instrument recordings of the Beethoven symphonies with the London Classical Players (released as a box set in 1989), Roger Norrington made a point of scrupulously following the metronome markings. Too scrupulously for Gardiner’s taste.

“Norrington made quite a fetish out of the metronome marks,” Gardiner said, “and it generated a fantastic surface attraction and excitement, but sometimes to me it meant that the music in the more expansive moments didn’t breathe. It was interesting, but to me it came out a little bit ‘samey.’ I didn’t hear any development, and that journey from the First to the Ninth Symphony through Beethoven’s career is crucial, because each symphony is built on the last one and adds something new.”

(Photo by Sim Canetty-Clarke)

In his takes on the symphonies, Gardiner does not follow the metronome marks “religiously” because he doesn’t think they all work. Instead, he sees them as indications of how Beethoven imagined the music in his inner ear, but that is very different than facing the practical reality of standing in a large hall in front of a group of musicians. “My feeling is that they are good starting points,” he said, “and sometimes they work really well if you slavishly follow them, and other times you need to be flexible and adjust them according to the time of day, the size of the hall, the size of the orchestra. I don’t think it is a belt-and-braces kind of panacea for success.”

Although Beethoven’s symphonies were written two centuries ago, Gardiner said, they represent a philosophical agenda — the composer’s humanistic and religious views and love of nature — that remains relevant. Three of the symphonies — the Third, Fifth, and Ninth, the last with its famous fourth-movement text taken from Friedrich Schiller’s poem, “Ode to Joy” — are directly political in nature and reflect events happening during Beethoven’s time. These three pieces also espouse in coded and direct ways Beethoven’s supreme belief in the values that emerged from the French Revolution of 1789 — liberty, equality, fraternity. “And they reflect very closely, it seems to me,” said Gardiner, “on the political situation of our time.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.

Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies, Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique and Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner, conductor

Carnegie Hall, New York (carnegiehall.org)

Feb. 19: Symphony No. 1, Prometheus excerpts, Leonore excerpts, “Ah! perfido”

Feb. 20: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3

Feb. 21: Symphonies Nos. 4 & 5

Feb. 23: Symphonies Nos. 6 & 7

Feb. 24: Symphonies Nos. 8 & 9

Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago (harristheaterchicago.org)

Feb. 27: Symphonies Nos. 8 & 9

Feb. 28: Symphony No. 1, Prometheus excerpts, Leonore excerpts, “Ah! perfido”

Feb. 29: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3

March 2: Symphonies Nos. 4 & 5

March 3: Symphonies Nos. 6 & 7