by John Mortensen

Published November 8, 2021

Improvisation leaves no trace. A performer invents something in the moment, and off it goes into the air, leaving behind no documentation. This is a central challenge in studying historic improvisation: Without documentation, is it possible to find out how musicians of the past improvised?

The problem is compounded by the last century and a half of music pedagogy, which has given the printed score a place of reverence. This idea of the printed score as the central object of importance is known as Werktreue, or “being true to the work.” In the philosophy of Werktreue, the musical world is organized around a canonical repertoire of printed scores, and the musician’s work consists of studying and realizing those scores with absolute fidelity to the composer’s intentions, which (it is assumed) are evident in the score.

What, then, are we to make of the misty legends of history’s improvisers, particularly those keyboardists of the 18th century who played without a score? Did Bach really toss off extemporaneous fugues? Were Mozart’s cadenzas actually invented on the spot? And if so, how did they know how to it, and why do we have so little historical documentation of the process? And does a world of Werktreue have any room for music that is not cemented in a score?

To answer these questions, we must first take account of ways that Werktreue has shaped and limited us. The centrality of the canonical printed score has helped fracture the academy into specializations. If the score is the main thing, then we need historical specialists to tell us about the conditions surrounding that score’s origins. We need theoretical specialists to provide mental categories for understanding its musical language. And we need fiercely loyal performers to channel the composer’s intentions as codified in the score. In the modern music academy, these are separate disciplines that rarely overlap; sometimes they are not even on speaking terms. Each specialization is cut off from the others, further narrowing the perspectives passed along to students.

Werktreue is not better or worse than any other approach on music. It is a set of assumptions that arose around a certain body of musical works in the last 150 years, and in some ways, it has served that body of work rather well. (One of the fruits of Werktreue is the pristine, meticulously prepared critical edition of the complete works of whomever you care to name.) But it is a particular and limited perspective that protects and nurtures some practices while nudging others off the table. It is emphatically not the perspective of history’s great improvisers, as it has no tools to deal with music that isn’t written.

Eighteenth-century keyboard musicians would be perplexed by our Werktreue-fractured academies and would hardly know what to make of someone who performed but never composed or someone who wrote great tomes about another’s music but never played any of it. They were trained as composers, performers, and improvisers simply because the working life of an 18th-century musician required all these skills on a daily basis.

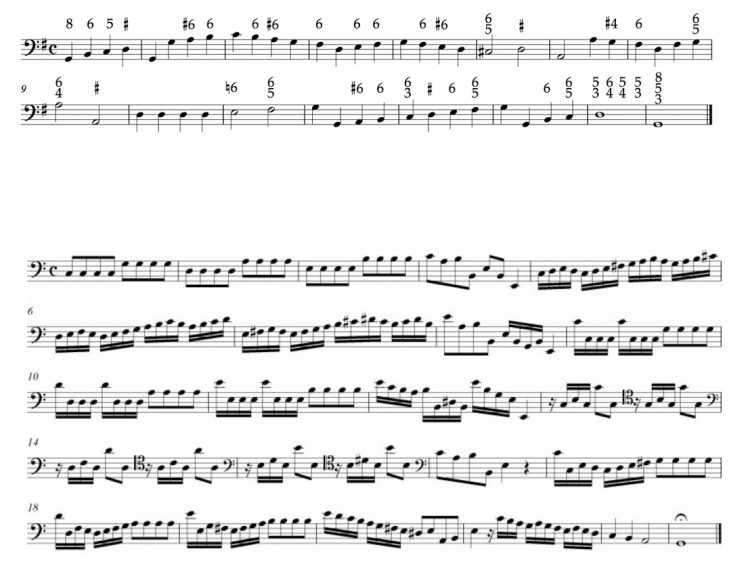

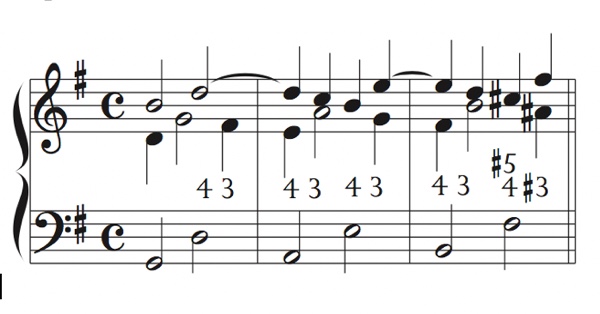

The conservatories of Naples provide a vivid example of the contrasts between today’s pedagogy and that of the 18th century. The Neapolitan schools were established to provide precisely this kind of multidisciplinary fluency. As career-oriented schools, their mandate was to train young boys (many of them orphans) into functional music professionals. This emphasis on the pragmatic skills of the working musician resulted in an equally pragmatic curriculum. They could not afford to indulge in abstract navel-gazing and philosophizing; they had to get students up to snuff and had no time to waste. Consequently, they developed a powerful, integrated pedagogy, of which a central component was partimento. A partimento is a pedagogical bass line. By observing the movement of the bass line, students trained in partimento could discern the appropriate harmonies for the upper voices. At more advanced levels, they could even tease out implications of imitation and invertible counterpoint just from looking at a bass line with no figures or other clues. Beginning and advanced partimenti of Neapolitans Fedele Fenaroli and Francesco Durante appear in Example 1.

Example 1. A figured, easy partimento of Fedele Fenaroli (top) and a difficult, unfigured partimento of Francesco Durante.

Important collections of partimenti (and treatises on their use) include those of Fedele Fenaroli (1730-1818), Leonardo Leo (1694-1744), and Giacomo Insanguine (1728-1795). But for those new to the world of partimento, the treatise of Giovanni Furno (1748-1837) is among the most accessible.

Furno’s Metodo facile breve e chiara ed essensiali regole per accompagnare Partimenti senza numeri (Easy, Brief, and Clear Method on the Essential Rules for Accompanying Partimenti Without Figures) begins by explaining intervals and the preparation and resolution of dissonance to consonance. It then presents a comprehensive system of harmonizing a scale in the bass known as the Rule of the Octave (RO). The Rule of the Octave provides harmony and voice-leading for every step of the scale, ascending and descending, major and minor. Students would memorize these patterns in every possible right-hand position and in a wide variety of tonalities. RO is the “please and thank you” of the 18th century — the correct thing to say in almost any situation, a widely applicable default language.

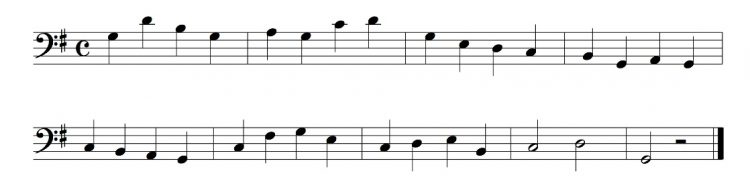

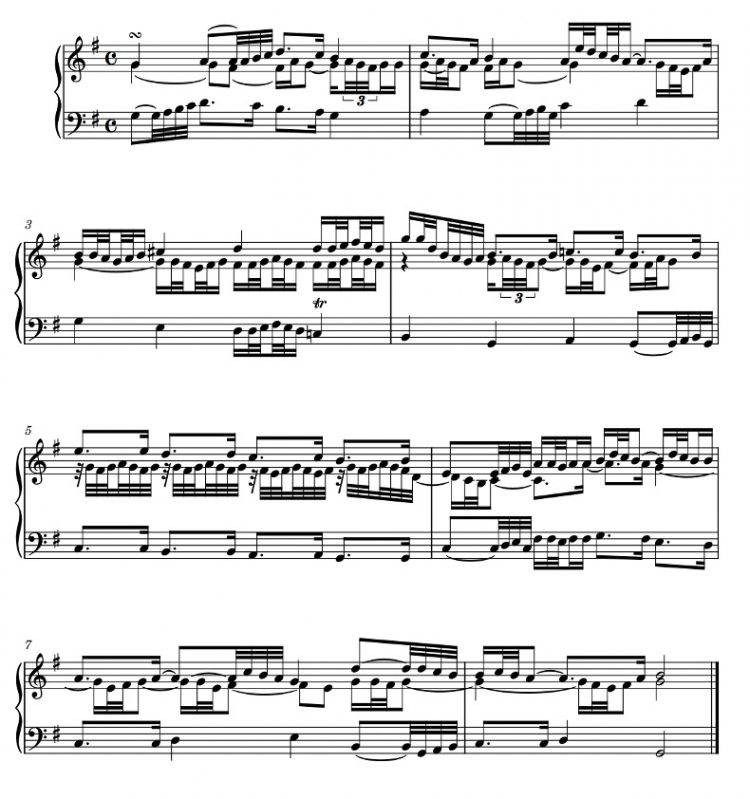

Armed with RO, students were ready for the Furno’s first partimento. Their task was threefold: to recognize, realize, and stylize. By observing the rising and falling of the bass, they were able to recognize what principles of RO should apply at any given moment. They could then realize a full harmony by adding upper voices. Finally, they could stylize the partimento into many genres of music. Example 2 shows Furno’s first partimento and Example 3 shows my stylization, which may be heard here.

Example 2. Furno’s first partimento, which must be solved using Rule of the Octave.

Example 3. My stylization of Furno’s first partimento.

After RO, Furno taught cadences and modulations. Again, characteristics of the bass line give cues about what techniques to apply. Next, Furno presented a selection of movimenti del partimento (bass motions), special bass patterns that take harmonizations other than RO. Taken together, RO, cadences, and movimenti form a comprehensive harmonic vocabulary of the 18th century.

There’s more. Advanced partimenti presented puzzles of imitation and invertible counterpoint. Partimento students learned that certain movimenti, when moved to an upper voice, easily fit with other movimenti in the bass. These combinations appear over and over in the partimento literature; after several years of work, a student could construct points of imitation and double (even triple) counterpoint with ease. Certain movimenti were taught with built-in contrapuntal devices such as canon in the upper voices. The pattern in which the bass rises by successive fifths, known today as Monte Romanesca, fits with a canonic set of upper voices that also create a series of dramatic suspensions. (The upper voices, by the way, may be inverted.) Contrapuntal secrets of this complexity were taught routinely to children. See Example 4.

Example 4. The “Monte Romanesca” as taught by Fedele Fenaroli.

Partimento was so effective because students learned its practices at the keyboard, not on paper. While some written-out partimento stylizations exist, for the most part it appears that the craft was undertaken without writing solutions. As far as scholars can tell, partimento study involved retrieving solutions from a mental library of schemes, modifying the schemes to fit the metrical, figurative, and rhetorical conditions of the moment, and developing these elements into a piece of legitimate music within the space of a few minutes. With this approach, the entire musical vocabulary of the time — harmony, voice-leading, contrapuntal patterns, sequences, dissonance/consonance relationships, and idiomatic keyboard figuration — were all absorbed simultaneously by ear, eye, hand, and mind from an early age.

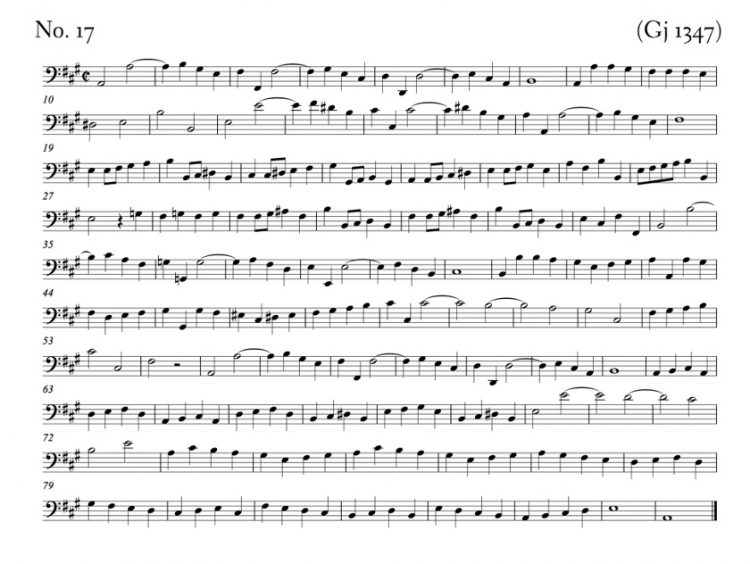

Fenaroli’s difficult partimento in A major is shown in Example 5. A video performance my realization is posted here.

Example 5. Fenaroli’s unfigured partimento in A major.

Once a student has absorbed the principles of partimento, improvisation is not only possible but easy and inevitable, because all the elements of music are at the ready. Eighteenth-century treatises didn’t say much about improvisation because they didn’t have to; improvisation was a natural side benefit of their overall pedagogical system.

The same recent scholarship that has opened windows on Neapolitan practices of improvisation has also made contemporary reclamation of those practices possible. An international revival of historic improvisation seems to be underway, driven not only by academic research but also by a sense of malaise among conservatory students who hesitate to embrace a musical ecosystem in which millions of performers play the same hundred pieces over and over. They wonder if such an ecosystem is sustainable or even desirable and are attracted to the idea that they could invent interesting, beautiful music in recognized historic styles, and do so in front of an audience in acts of spontaneous creation.

A student at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, UK, explained this malaise by telling me that in devoting oneself solely to performing standard repertoire, a student could never hope to reach the level of Horowitz or Sokolov or Cliburn. The best one could hope for is to be an inferior imitator of the greats — a gloomy prospect, indeed. This student believed that in the 21st century, a player of standard repertoire cannot expect to make a truly unique contribution to the world of music.

Having discussed these matters with countless students from across the world, I have become convinced that the classical music realm is increasingly receptive to historic improvisation, not only as an academic curiosity but also as a potential equal partner on the stage with composed repertoire. In order to make improvisation resources available to students, I have invested effort in several projects.

My website (johnmortensen.com) features live, unedited video of historic improvisation in concert from tours in the USA and overseas.

Improv Planet is an online school of historic improvisation. Participants include members of internationally recognized orchestras, faculty from leading conservatories, collegiate music students from around the world, and avid amateurs. Improv Planet hosts the world’s largest collection of historic keyboard improvisation video tutorials.

The U.S. State Department’s Fulbright program sponsored my performing and teaching tours hosted at the Cork School of Music, Jazeps Vitols Latvian Academy of Music, the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, Royal Northern College of Music, Chetham’s School of Music, and the Royal Danish Academy of Music – Aarhus. Watch a video of one of my students from Latvia improvising a fugue.

Plans are underway to organize an international improvisation festival based in Denmark. This event, designed for conservatory-level students, will feature intense study with leading performers of historic improvisation, along with public concerts, in an idyllic Danish setting. Depending on circumstances related to COVID-19, it will begin in the summer of 2022. Once international travel conditions have stabilized, the festival will be publicly announced.

In May 2020, Oxford University Press published my book, The Pianist’s Guide to Historic Improvisation. Written for professional musicians and educated amateurs who are proficient keyboardists but have never improvised, the volume offers historic techniques for creating extemporaneous music. After beginning with simple “building blocks” such as opening formulae and sequences that can be assembled into short figuration preludes, the reader encounters increasingly complex challenges including dance suite, diminution, imitation, partimento, and schemata. More information about the book is at johnmortensen.com.

My next book, complete and approaching publication, will be called Improvising Fugue. It explores fugue improvisation through the study of partimento. Like The Pianist’s Guide to Historic Improvisation, it is a practical method intended to lead the reader to fluent and spontaneous creation of fugues at the keyboard.

More resources for the aspiring improviser are appearing at an encouraging rate. Giorgio Sanguinetti’s important book The Art of Partimento is required reading for anyone interested in that tradition. Robert Gjerdingen’s Child Composers in the Old Conservatories provides a vivid picture of musical training in 18th-century Naples. Nikhil Hogan’s podcast from Singapore features interviews with leading scholars and performers in the world of historic improvisation. Harpsichordist Ewald Demeyere has started a series of YouTube demonstrations of partimento realization. Derek Remeš offers materials on his website in the areas of partimento and figured bass.

These developments suggest that although the reign of Werktreue banished improvisation from public view for many years, spontaneous music invention at last has begun to find its way back to the concert stage. Partimento was once a central pillar of training in early music. Forgotten for a century, it is now being rediscovered by keyboard artists who aspire not only to recite music but also to create it.

John Mortensen is a leader in the international revival of historic improvisation. Appearing frequently as concert artist and masterclass teacher in America and Europe, he is noted for his ability to improvise entire concerts in historic styles. He is the author of The Pianist’s Guide to Historic Improvisation (Oxford University Press, 2020). A Fulbright Global Scholar in Historic Improvisation, he serves as professor of piano at Cedarville University in Ohio. In 2016, he was named Faculty Scholar of the Year, that institution’s highest award.