by Jeffrey Baxter

Published September 25, 2023

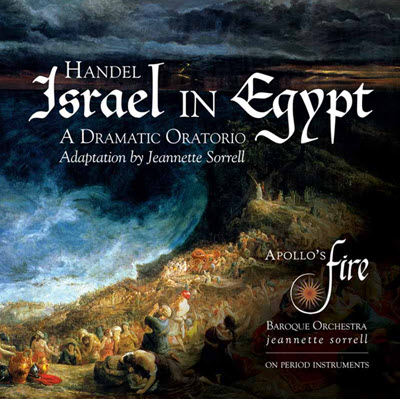

Handel: Israel in Egypt (Adaptation by Jeannette Sorrell). Apollo’s Fire and Apollo’s Singers, with sopranos Margaret Carpenter Haigh and Molly Netter, countertenor Daniel Moody, tenor Jacob Perry, and baritone Edward Vogel, conducted by Jeannette Sorrell. Avie Records AV2629

The latest recording from Apollo’s Fire, of Handel’s well-loved Israel in Egypt, is the result of the ensemble’s 2017 premiere of an “adaptation” by the ensemble’s conductor, Jeannette Sorrell. Her version involves the re-ordering, cutting, and replacing of movements and the partial restoring of an entire section. Such adjustments are not unjustified, given both the strange genesis of the work and Handel’s subsequent tinkering with it.

The latest recording from Apollo’s Fire, of Handel’s well-loved Israel in Egypt, is the result of the ensemble’s 2017 premiere of an “adaptation” by the ensemble’s conductor, Jeannette Sorrell. Her version involves the re-ordering, cutting, and replacing of movements and the partial restoring of an entire section. Such adjustments are not unjustified, given both the strange genesis of the work and Handel’s subsequent tinkering with it.

In a mighty creative burst in 1738, Handel began the English-language oratorio by newly composing, assembling, and heavily borrowing from his own and other composers’ music. He worked in reverse order, starting with what today is Part III, “Moses’ Song” (a multi-movement anthem, composed in 11 days). He then expanded that with a prefatory epic, a setting of the Exodus itself and the Biblical plagues (now Part II), and then reworked his 1737 funeral anthem for Queen Caroline to serve as an Introduction (now Part I), ending up with a full-blown three-act oratorio. While recognized as a dramatic tour de force, containing some of Handel’s most creative and descriptive writing for chorus and orchestra — a “choral opera” in a sense — the work’s uneven narrative is problematic. It was a colossal flop at its premiere.

It is thought that the opera-going audience in 1739 might have been put off by religious texts presented in the theater (as happened with Messiah a few years later) and that the heavy use of the chorus (a score with nearly 40 chorus numbers but only four arias and no named characters) may have seemed a bit much, even in Lent. For the second performance, Handel quickly made adjustments, advertised in print at the time as “short’ned and Intermix’d with Songs,” cutting all of Part I and adding several solo arias, some in Italian. He continued this practice of “editing” up until 1756, when he last revived the piece.

Jeannette Sorrell explains her approach:

“The piece has a dramatic arc… However, if performed in full, it would last over three hours. So in modern times, the original Part I is very rarely done. In fact, most published editions contain only two parts, referring to Exodus as Part 1 and Moses’ Song as Part 2.

“To me, Handel’s original conception of the piece is masterful… But the 30 minutes of triumph in Moses’ Song can only be meaningful if we have come from a place of grief beforehand, as Handel originally conceived it… So I have restored Act 1.

“But in order to keep the length of the oratorio manageable for modern audiences [at 74 minutes], I have made cuts throughout the oratorio — some of them small, others larger — with the goal of preserving the storyline but tightening up the dramatic pacing. I have omitted some movements, but for the most part I have made cuts within movements, in order to preserve the story but make it move more quickly.”

Sorrell’s adaptation of Part I includes five movements (plus the Overture) of Handel’s original 13-movement design. After the sensitively played opening Sinfonia, we hear the chorus’ somber “The sons of Israel do mourn,” a text Handel reworked from “The ways of Zion do mourn.” The melodic contour of this opening section, with its plodding accompaniment and wailing introductory winds, very much reminds the modern listener of the opening of Mozart’s Requiem (influenced by his exposure to the music Handel and Bach by Baron van Swieten).

Next, Sorrell compresses into one movement Handel’s 3-part chorus, “How the mighty is fall’n,” cutting each movement that falls in between. To complete Part I, only the next two choruses are included, “The righteous shall be had” (featuring a solo-trio and whose orchestral introduction foreshadows the overture of Messiah, with its 8th-note figuration and harmonic progression) and “Their bodies are buried in peace,” a sensitive declamation that recalls Purcell’s funeral sentences for Queen Mary. Of special note is the Apollo Singers’ sensitivity to text, where a slight break is made between “buried” and “in peace.” The effect is breathtaking, without being detracting or mannered.

Handel’s final three choruses of Part I are cut here, but the harmonic sequence is retained — ending Part I in C Major and leading into Part II’s opening F Major.

Of Frogs and Thunder

The oratorio’s fame rests in the inspired writing of Part II, a sizzling setting of a “blood and thunder” Old Testament tale. Handel threw in every technique at his disposal, but now aimed at the choral singers, demanding them to deliver recitative, arioso, fugue and double fugue, bold homophonic (and unison) statements, virtuoso coloratura, and double-choir antiphonal “call and response.” Orchestrally, too, he writes for a richness that includes trombones (in 13 of the movements), trumpets (in six), and solo timpani (separate from the accompanying brass in one key scene).

Of the 16 movements Handel created for Part II, Sorrell retains 10, but also cuts much material, such as in the first chorus, “And the children of Israel sighed,” where the central section of repeated text, “sigh’d, sigh’d,” is excised, leading directly to the choral bass entry at the end.

But perhaps the most egregious omission is the cut of the first of the 10 Biblical plagues — all of them set by Handel — to make a mere nine Biblical plagues. Since Sorrell eliminated the stern and highly chromatic “They loathed to drink of the river: He turned their waters into blood” (a four-voice fugue), she made an adjustment in the final line of the preceding tenor recitative, changing, “He turned their waters into blood” into “He caused their land to bring forth frogs,” leading directly into the alto aria about invasive amphibians in Plague No. 2. “Frogs” is brilliantly scored for the male alto voice, here sung by Daniel Moody with superb textual declamation, clarity of line, and a playfully ornamented “hopping about” in his final cadenza.

In the chorus “He spake the word: And there came all manner of flies,” Handel’s brilliant use of trombones is featured (not only for choral colla parte support but for instrumental color). Any modern listener can hear in the echo of the first sung line the composer’s magic that surely inspired Mozart in his Magic Flute. After the two-measure intro, Apollo Fire’s violins deftly toss off the figuration depicting the buzzing of flies and, later, the swarming of locusts.

In “He gave them hailstones for rain” Sorrell unfortunately chooses to double-dot the rests in the orchestral introduction, shortening the anticipatory 8th notes into 16ths, and in the process sullying Handel’s intended depiction of the gradual arising of a storm: the innocent raindrops arrive first as a series of repeated 8th notes that turn to menacing hail in a cascade of 16th notes. Then comes the thundering double-choir climax of a full-blown storm. Skillful timpani playing (with rolls added to support crescendi) enhances the drama.

Sorrell makes an interesting interpretive choice in the choral recitative “He sent a thick darkness,” using solo voices near the end for the individual sung lines of declaimed text, until the final bass statement (“even darkness which might be felt”), which is here sung by the choral basses to great dramatic effect.

Sorrell cuts Handel’s next two choruses. “But as for his people, He led them forth like sheep,” a beautiful pastorale — and, notably, the only moment where flutes are in the score — does not move the drama forward. And the chorus “Egypt was glad when they departed” (a stern tempo giusto fugue borrowed almost in its entirety by Handel from J. K. Kerll) is here jettisoned.

In “He rebuked the Red Sea,” an expertly sung unaccompanied refrain, the line “and it was dried up” conveys a hushed incredulity of the miracle. There follows “He led them through the deep” (a quasi-chaconne), performed with cuts at the center and thereby removing Handel’s musically florid “wilderness” of 16th notes.

Handel’s final two choruses for Part II (cut in this version) include “And believed the Lord,” a slow-moving four-voice fugue in ¾ that bears a strange resemblance in mood to the “Crucifixus” from Bach’s B-Minor Mass. Instead, Sorrell chose a strong allegro ending for Part II with “But the waters overwhelmed their enemies,” a four-voice chorus, complete with Handel’s rumbling timpani. The dramatic cut and thrusts on the words “not one” are carefully balanced by the ensemble’s choice to vary the dynamics and apply skillful sostenuto singing on the text’s full phrases, “there was not one.” But at just over a minute, is this perhaps too abrupt an ending for Part II?

Still, the choice to end Part II with the dramatic sinking of the Egyptians into the Red Sea feels correct and balances Handel’s similar ending of Part III (“Moses’ Song”), which also recalls — to great fanfare — how the horse and rider are thrown into the sea.

The Sublime and the Bravura

Of Handel’s original 17 movements for “Moses’ Song,” Sorrell has retained 13 (including a movement transferred from the 1756 version of Part I).

With a “Zadock the Priest”-like choral outburst, Handel begins his tour-de-force choral finale with “Moses and the children of Israel,” here dispatched with aplomb in the laser-like accuracy of 16th note melisimas. The phrases pile one atop another — wave after wave — to great effect as the horse and his rider are thrown into a swirling sea of masterfully controlled counterpoint.

“The Lord is my strength” is a contrasting lyrical duet superbly sung here by equally matched soprano voices (Margaret Carpenter Haigh and Molly Netter) who highlight Handel’s written-out vocal cadenza of triplet-figuration near the end with a slight relaxing in tempo.

“He is my God,” an eight-voice chorus in homophonic declamation and harmonies that recall Purcell, Schütz, and Monteverdi, was originally intended by Handel as a brief introduction to his next chorus, “And I will exalt him,” an old-school alla breve four-voice fugue. Sorrell cuts the fugue (as well as the familiar ensuing duet, “The Lord is a man of war” — with its hints of Messiah’s “The trumpet shall sound”). Instead, they use Handel’s 1756 interpolation from his Occasional Oratorio, “To God our strength.”

In this 7-minute two-part movement, sublimely introduced by solo trumpet and oboe (here matched perfectly in tone and timbre by Steven Marquardt and Debra Nagy), the bass voice introduces the text in an atmosphere similar to Handel’s “Eternal source of light divine” from his 1713 Birthday Ode for Queen Anne. At the chorus’s allegro entry, Miriam’s Old Testament tambourine is depicted in Handel’s violins at the text, “the timble hither bring” — here cheekily dispatched by Apollo Fire’s nimble violins.

In “Thy right hand, O Lord,” Sorrell cuts the adagio ending, as well as the next two choruses: “Thou sentest forth thine wrath” (a stern A-minor ricercar) and “With the blast of thy nostrils” (with its many colorful effects recalling the parting of the Red Sea). The cut makes sense though, as it leads logically into the ensuing bravura aria, “The enemy said.”

Here Jacob Perry tosses off the only tenor aria in the whole work with panache, snarling at the text, “I will draw my sword,” but without ever losing drive — or tempo. It is followed by “Thou didst blow,” a contrasting soprano aria featuring imaginative writing for bassoon and viola that depict a gentle, rather than terrifying, wind.

Sorrell’s choice to perform “Who is like unto thee” with basso continuo only (no doubling instruments) until a forte statement of “Thou stretchest out thy right hand,” is dramatically effective and beautifully executed. She cuts the ensuing chorus, “The earth swallowed them” (a stern alla breve fugue) and launches into Handel’s final brilliant closing numbers (with one small cut in “The people shall hear”).

The performance on this recording is so compelling that one wishes it were a more complete, uncut version, allowing the listener at home to listen whole or make their own cuts. But since that never existed — even for Handel — this quasi-live 21st century “concert experience” is a welcome addition to the recorded catalogue.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired Choral Administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw in his final years. He holds the doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL.