(Photo by Mark Taylor)

By Tim Diovanni

DUBLIN — Each Christmas season, churches, universities, choirs, and high schools across the United States perform Handel’s Messiah. You’re practically guaranteed to hear it at least once on the radio, in a concert hall, in a mall, in a church, on the news, or in a grocery store.

The situation is remarkably similar in Ireland: Musicians throughout the island produce the oratorio for audiences who ritually congregate to witness it.

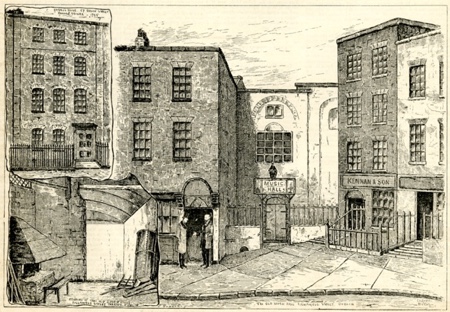

Its tremendous popularity in this country can, in part, be attributed to its premiere, which occurred in Dublin — the nation’s capital — on April 13, 1742. On that date, more than 700 people squeezed into Mr. Neale’s Music Hall on Fishamble Street, a venue that could comfortably fit 600. Proceeds from ticket sales, totaling almost 400 pounds, were distributed to the city’s three largest charities — the Society for Relieving Prisoners, Mercer’s Hospital on Stephen’s Street, and the Charitable Infirmary on Inns Quay — which received 127 pounds each, a significant sum at the time.

Each year on April 13, Our Lady’s Choral Society and the Dublin Handelian Orchestra commemorate the premiere with an hour-long Messiah on Fishamble Street in front of the spot where the Music Hall once stood. Proinnsías Ó Duinn has conducted this concert — aptly entitled “Messiah on the Street” — since 1992, the 250th anniversary of the premiere. Dublin City Council sponsors the event, which draws a crowd that fills much of the street.

A video of the “Messiah on the Street” event in 2007 from RTÉ News shows two women flipping through a score, a baby boy gleefully smiling, and listeners and chorus members — prompted by Ó Duinn — throwing their hands in the air on the word “Hallelujah” during the famous ebullient chorus.

“It’s wonderful to see a number of young people and children at the event and in rapt attention, perhaps fascinated by the orchestra, the choir, or the music,” says Paul Kenny, a bass in the chorus who suggested the commemoration to Ó Duinn in 1991. “It is a privilege to be part of a wonderful group of friends who know the work so intimately, who love singing Handel’s glorious music and the sacred text compiled by Charles Jennens, and to bring that uplifting annual celebration to the people of Dublin and the world.”

Not everyone in Dublin, however, has held such a positive view on Messiah. In an article published in The Irish Times in 2000 under the headline “Oh God, not another Messiah,” Robin Hilliard, a chorister and organist, proposed a moratorium on the complete oratorio during the holiday season because it had become a “stuck record” that excluded “equally enjoyable works.”

As Hilliard wittily lamented: “[I]t’s the Christmas season and it’s marked by the galloping apathy of every chorister and choristrette, choirmaster and mistress, organist, leaden violinist and conductor, in his or her presentation of Handel’s sine qua non to a public which has heard it all before.”

Organizations could “give other composers and music a look-in,” Hilliard wrote, programming Bach’s Christmas Oratorio or Monteverdi’s Christmas Vespers, which are appropriate for the holiday.

Early music ensembles and symphony orchestras, however, would probably never remove Messiah from their schedules because of its monolithic popularity. The oratorio helps to fund their seasons, allowing them to promote and produce other works, which often result in financial losses. A chef wouldn’t dig out another recipe from the cupboard if the prime steak that she’s serving is the only dish she knows her costumers will buy.

Peter Whelan, artistic director of the Irish Baroque Orchestra, has innovatively exploited the renown of Messiah. Whelan uses the work as a “starting point” to introduce audiences to little known composers and musicians who were active in Ireland in the 18th century. One example is Matthew Dubourg, a composer and violinist who studied under Francesco Geminiani. From 1728-1752, Dubourg led the Irish State Music, the official band of Dublin Castle, which performed in the premiere of Messiah.

At Dublin Castle in August 2017, Whelan — who’s also a keyboardist and bassoonist — conducted the Ensemble Marsyas, of which he is the founding artistic director, in a program called “Rediscovering Irish State Musick.” The concert featured royal odes by Dubourg taken from manuscripts at the Royal College of Music in London. Since then, Whelan has recorded Dubourg’s ode, “Crowned with a more illustrious light,” with the Irish Baroque Orchestra for a CD titled Welcome Home, Mr. Dubourg!, which will be released in April.

Unearthing and presenting composers and musicians like Dubourg, Whelan advocates for a heritage of Western art music that contemporary Irish audiences — at home and abroad — can feel proud of. He fondly remembers directing the Portland Baroque Orchestra in an educational concert series called “Music from Dublin Castle,” which included works the Irish State Music played in the 18th century, in November 2017. At one of the concerts, children arrived in green shirts because the program was about Dublin Castle. Whelan recalls that “the parents were absolutely delighted to be able to introduce an aspect of Irish culture that didn’t involve drinking or St. Patrick’s Day.” Whelan has taken his project elsewhere, affecting many with a claim to Ireland.

Since Irish musicians routinely produce Messiah, their interpretations could, over time, become stale. Ó Duinn avoids turning out a dull rendition by emphasizing the “theatrical drama of the piece,” particularly in Part Two and Three. He also sets tempos that were once deemed “fast and uncomfortable” in Ireland; however, they are now “considered correct” and enjoyed by singers.

While Ó Duinn churns up excitement through musical means, Whelan creates fresh interest by trying to replicate the experience of the premiere. To this end, he uses the version of Messiah that was presented in Dublin at the 1742 concert. The most significant difference in this version, Whelan says, is how Handel adapted it for the personality of the singer and actress Susanna Cibber, who performed a central aria in each third of the work, “each designed to pull at the heartstrings.” The second of these three arias — “He was despised and rejected” — sounded especially relevant for Cibber because she had recently fled to Dublin after a disastrous sex scandal in London.

Whelan has been considering two other ideas that could recreate the atmosphere of the premiere. He wants to produce Messiah in a venue roughly the size of Mr. Neale’s Music Hall instead of in a cathedral, where the oratorio is typically heard. The concert setting, the conductor believes, is more faithful to the premiere because its acoustics are more immediate than a cathedral’s. Whelan is searching for such a space in Dublin, focusing his investigation on structures that were designed by Richard Cassels, the architect of Mr. Neale’s Music Hall.

Whelan also would like to employ a popular singer and actress to perform the arias Cibber sang. Someone “from outside the world of ‘Classical Music’ who is an edgy and vulnerable communicator, like Camille O’Sullivan,” he suggests, “could make the context more real.”

Tim Diovanni is a music writer from New York and a graduate student in musicology at the Dublin Institute of Technology.