Although the harpsichord was almost completely supplanted by the piano after enjoying an extraordinary heyday that stretched from the 16th through 18th centuries, composers in the 20th and 21st centuries have returned to the instrument in modest ways. Francis Poulenc and Manuel de Falla both wrote concertos for the instrument, and Elliott Carter composed his Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras in 1961.

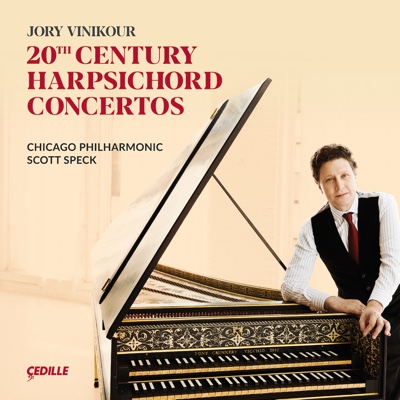

Other composers have written works for the instrument, and four of those compositions are collected on 20th Century Harpsichord Concertos, an album released in June on the Chicago-based Cedille Records label. It features soloist Jory Vinikour, conductor Scott Speck, and the 31-year-old Chicago Philharmonic. Vinikour is best known for his performances in early music, but he proves himself to be an equally adept interpreter of this modern repertoire. And the orchestra more than holds its own, with admirable solo work by several of its principal musicians.

In 2013, Vinikour released Toccatas, a Grammy-nominated album of 20th-century American solo works for harpsichord, and the new recording is a kind of follow-up. It features four nicely contrasting works that stretch across more than 60 years, ranging from the romanticism of Walter Leigh to the idiomaticity of Ned Rorem and minimalism of Michael Nyman. Vinikour had originally considered including concertos by Bohuslav Martinů or Henryk Górecki as the fourth selection but in the end settled on Viktor Kalabis’s dark, unsettled Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, Op. 42.

“It just hit me very strongly that that was the work I needed to record,” he said. “It was under-represented. It had only been recorded once by Kalabis’s wife, Zuzana Růžičková, a long time ago. I found the work very compelling.”

Headlining the album is the world-premiere recording of Rorem’s Concertino da Camera. It was written in 1946, when the American composer was just 23 and palling around with Daniel Pinkham, who became a noted harpsichordist, organist, composer, and teacher. The piece was completed just two years after Aaron Copland’s Applachian Spring, and the older composer’s influences are evident here in Rorem’s distinctly American vernacular harmonic language. It’s a little jarring at first to hear a harpsichord — especially with some of the Baroque flourishes Rorem adds for the instrument — in this stylistic world, but the composer manages to effectively interweave it in the fabric of this appealing work.

The soloist in the concerto, which is really more of a chamber work, collaborates with seven accompanying instruments, giving the piece an open feel, with the harpsichord and solo cornet occasionally sharing the spotlight. The piece was not performed upon completion, and Rorem wound up shelving it. Vinikour got wind of the work and managed to obtain a copy of the score from the Ned Rorem Archives at the Library of Congress with the help of the composer’s niece. It had never been typeset, let alone published, so Vinikour’s partner, Philippe LeRoy, prepared a usable version of the score. This is the first time the work is being heard outside a student performance at the University of Minnesota in 1993.

“It’s really a delightful piece,” Vinikour said, “which merits being performed, though it is quite challenging for the soloists and all of the musicians. So, this is a big deal.”

The British-born Leigh, composer of the Concertino for Harpsichord and Strings, served in World War II and died in action in 1942 just before his 37th birthday, ending a highly promising career. His nine-minute work, written in 1934, is Leigh’s best-known creation. “It’s extraordinarily charming,” Vinikour said. “I feel always that it represents this pastoral, English, neo-folkloric style, so, in other words, looking at (Ralph) Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth.” The soloist praises the composer’s understanding of the harpsichord: “He just got the instrument and got how it balances against the strings.”

Czech composer Kalabis, who died in 2006, married Růžičková, a childhood survivor of three Nazi concentration camps, in 1952. Despite refusing to join the Communist Party and facing persecution during the Soviet domination of their native country, the two nonetheless managed to carve out productive careers and garner international recognition. Růžičková served on the jury of the Prague Spring International Music Competition, at which Vinikour took top prize in 1994. The following year, when he returned for the winner’s recital, Vinikour and his father were invited to the home of the two musical figures for tea. The elder harpsichordist was aware that this recording was underway, and the Viktor Kalabis and Zuzana Růžičková Foundation provided support, but she died (in 2017) before it was released.

Conductor Speck and Vinikour found Kalabis’s Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings, Op. 42, to be the most emotionally profound of the four on the recording, especially the slow second movement, which the former described as a “cry from the soul.”

“We were all moved by that piece when we were recording it,” Speck said. And it is hard to disagree with his assessment. This disquieting piece was composed in 1974-75, and it seems to bare the pain of oppression that Kalabis, Růžičková, and, indeed, the entire country suffered behind the Iron Curtain. In Kalabis’s skilled hands, the harpsichord takes on a decidedly contemporary flavor, with the soloist delivering an appropriately sharp-edged, sometimes strained sound. Particularly affecting is the desolate, sometimes angry second movement, with extended lines in the strings offset with blunt, discordant chords and manic progressions on the harpsichord.

“This is a piece that is telling some kind of a story,” Vinikour said. “The second movement is awfully dramatic. I don’t hesitate to the call the work an absolute masterpiece, so I’m not only glad that I recorded it, I’m relieved that I recorded it.”

English composer Nyman, whose Concerto for Amplified Harpsichord and Strings closes Vinikour’s recording, is most admired for his film scores, including those for Jane Campion’s The Piano and many movies directed by Peter Greenaway, such as The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982). He composed the concerto in 1994-95 for Franco-Polish harpsichordist Elisabeth Chojnacka, who played the world premiere in London under the composer’s baton in 1995. Vinikour has performed the work with several ensembles, including six performances with French conductor Marc Minkowski. The harpischordist describes the piece as having a kind of “rock ’n’ roll” flavor because of its driving rhythms, especially in the electric, tango-inspired cadenza.

“It is a real handful,” Vinikour said. “Despite the minimalist language, he asks a great, great deal from the strings both in range and rhythm, and the harpsichord part is a wrist-breaker and very difficult to learn.”

Performing concertos like these in concert can present problems in achieving the right balance between a modern orchestra and the harpsichord, which can’t come close to matching the sonic power of a nine-foot concert grand piano. But the engineers working on Vinikour’s recording made sure that is not an issue. Instead, the main hurdle was an interpretative one — animating these little-known works. “Finding the life within this music,” Speck said, “and finding the composer’s intention — those became the challenges for this recording.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.