by Anne E. Johnson

Published November 24, 2024

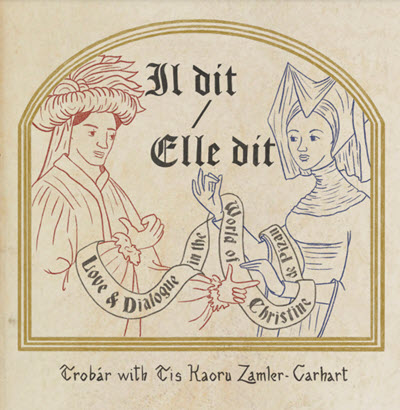

Il dit / Elle dit: Love & Dialogue in the World of Christine de Pizan. Trobár, with Tis Kaoru Zamler-Carhart. Released by Trobarmedieval.org.

In the program booklet for Cleveland-based Trobár’s new album Il dit/Elle dit, Allison Monroe explains that the all-female ensemble has had trouble finding music to program in the “extremely male-centric” repertoire of late-medieval song. “When women speak,” writes Monroe, “they often seem to be merely puppets for the author’s ventriloquism,” or else, as subjects of poetry, women are “spoken of in degrading or even openly misogynistic terms.”

Hence this project to honor the illustrious Christine de Pizan, the setting of whose poem “Dueil angoisseus” to music by Gilles Binchois is a unique example of attribution for a female poet among the 14th- and 15th-century song repertoire.

Monroe also points to Trobár’s wish to learn the rarely performed songs composed for two equal voices (rather than solo voice). By chance, Monroe and fellow Trobár members Elena Mullins Bailey and Karin Weston found that such songs are often told from a woman’s point of view. And, given the anonymous transmission of poetry in that era, who knows? Some of the songs may have lyrics by actual women — maybe even Pizan herself.

Of course, Binchois’s setting of “Dueil angoisseus” is among the album’s offerings. Some other famous names make an appearance: Guillaume de Machaut’s “Quand je suis” is a monodic song which Trobár vary by interspersing solo with unison singing. Guillaume DuFay’s “La belle se siet,” one of the album’s highlights, features two flowing, love-soaked voices accompanied by Monroe’s vielle on the slower-moving tenor line.

There are a handful of lesser-known composers. Johannes Reson (fl. c. 1425–35) is represented by the two-voice motet “Ce rondelet/Le dieu d’amours,” the two texts sung a cappella with a delightful lilt, but neither having an obvious connection to women. To be fair, the title of the album translates as “He says/She says,” so there’s no mandate for a female perspective.

The other named composers are Johannes Cesaris (fl. 1406–17) and Pierre Fontaine (c. 1380–c. 1450). However, the majority of the pieces have no known attribution for either composer or poet. This is not simply a choice of practicality. Anonymous composers, explains Monroe, “deserve our attention just as much as those by named creators. They could well hide the work of a woman.” A two-voice song called “Qui n’a le cuer,” involving lots of octave leaps and a few wonderfully weird dissonances, is a particular treat, sung with exquisite intonation by Weston and Mullins Bailey.

Although no other musically set poems can be attributed to Pizan with certainty, she is omnipresent on this album. The music stops every few tracks for spoken recitations of her verse in a supple, expressive voice by guest artist Tis Kaoru Zamler-Carhart, who also provided the well-crafted translations of all the lyrics in the booklet.

Poetry is the main focus, yet this album is not just about the voices. There are a handful of short instrumental tracks, all played by Trobár members. The anonymous “Dame playsans,” full of sly rhythmic surprises, is performed as a duet between vielle (Monroe) and what sounds like a low harp (both Mullins and Weston play versions of that instrument). In a contrasting style, the harp plays only a single note to every five or six on the vielle in “Elas mon cuer” from the Faenza Codex.

Produced by Steven Plank and Monroe without a record label, the sound captured at Church of the Resurrection in Solon, Ohio is always clear and vital, well balanced among the voices and instruments.

Anne E. Johnson is the EMA Books Editor and a frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently reviewed Lodovico Viadana’s stunning Sacri Concentus.