by Rebecca Cypess

Published July 29, 2024

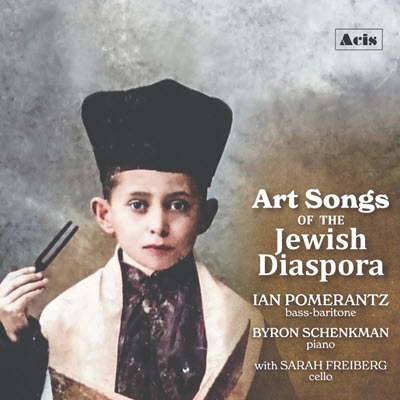

Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora. Bass-baritone Ian Pomerantz, pianist Byron Schenkman, cellist Sarah Freiberg. Acis Productions APL54115

Diverse experiences in the Jewish diaspora — of geographies, cultures, and no fewer than six languages

Bass-baritone Ian Pomerantz was a graduate student in historical performance when he began to confront the lack of representation of Jewish composers and of the Jewish experience in the standard art song repertoire. With a strong interest in cantorial music — he is now studying cantorial arts at Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam, Germany, while simultaneously pursuing a doctorate in musicology at the Sorbonne-Cité in Paris — Pomerantz knew that the canonical status quo failed to capture this important aspect of musical history. So began a years-long project to unearth art songs that reflect the wide-ranging meanings and experiences of the Jewish diaspora from the 19th century to the present.

If one defines “early music” narrowly, as music composed or practiced before 1800, then the recording Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora does not qualify as such. But, as Pomerantz and his collaborator, pianist and historical keyboardist Byron Schenkman, explain, the recording is deeply rooted in the methodologies of historical performance, including a complex notion of authorship, the recovery of long-buried sources, the reconstruction of score fragments, and a creative re-imagining of musical practices that have been lost to time.

I spoke with Pomerantz and Schenkman in May 2024 with a view to understanding the contribution that Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora makes, both musically and culturally. In some ways, their work mirrors that of other musicians who help diversify the repertoire by recovering and performing works by composers from underrepresented ethnic or racial groups. Yet this project also diverges from those other initiatives, and it highlights the unique status that Judaism holds in history and society. After all, Judaism does not fall neatly into the modern categories of race, ethnicity, or religion. And, even today, as antisemitic harassment and violence are on the rise, antisemitism is still actively denied by many people who are otherwise committed to advancing the cause of social justice.

As a sounding manifestation of Jewish history, Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora constitutes an important statement about the Jewish experience. While the Jewish diaspora is full of stories of persecution and loss — representative of what has come to be called the “lachrymose” narrative of Jewish history — it was important to Pomerantz and Schenkman that their recording convey a more complex set of experiences.

As Pomerantz explained, “To me, the recording has a clear emotional arc and an internal thematic unity about exile, refugee status, and persecution, but ultimately resilience.”

The 10 composers whose music is included in this recording lived in diverse geographic and cultural situations, spanning numerous ethnicities, and their experiences are far from uniform. Indeed, the songs in it are in no fewer than six languages: English, Hebrew, Yiddish, Spanish, French, and Ladino.

For Pomerantz, the diversity of experiences represented in the Jewish diaspora was a key feature of the project. During the research process, he built lasting relationships with composers as well as their heirs and keepers of their estates, giving the project a deeply personal aspect. “I went through a lot of manuscripts and out-of-print music that had never been recorded,” he said. “I wanted to reflect the diversity of the Jewish diaspora. We have several Ashkenazi composers [i.e., those with roots in central and Eastern European communities], several American composers, several Sephardic composers — that’s the background of my father’s mother.”

This family connection proved central to Pomerantz’s conception of the project as it developed: “It was meaningful to me because singing classical music in Ladino — the language of the Sephardic Jews — is something we don’t often think about. It’s an endangered language. Native speakers are generally over 75 years old now. I felt like I was doing some important language revival.” Pomerantz’s personal connection to the project is signified visually on the back cover of the CD booklet, which shows a portrait of his great-great-grandfather, Mordeachai Kallos.

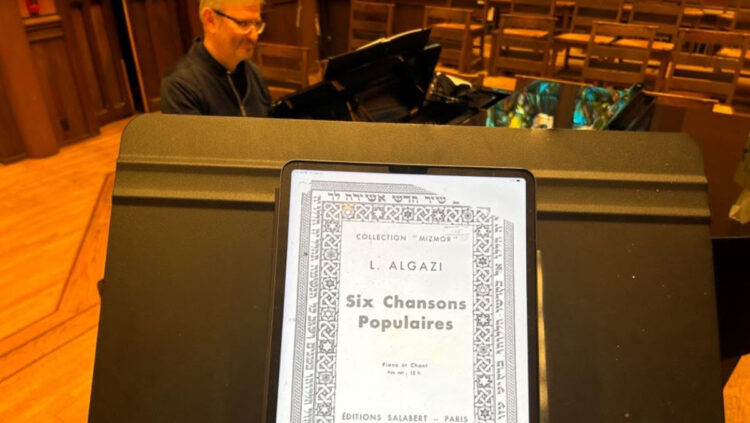

Readers are encouraged to explore the extensive liner notes that accompany the recording, but I will present a few case studies here to illustrate both the methodologies that lie behind the project and the statements that it makes. Composer Léon Algazi (1890–1971) was, like part of Pomerantz’s family, from a Sephardic Romanian background, though he emigrated to France and hid in Switzerland during World War II. Two of Algazi’s Six chansons populaires, with texts in Hebrew, are included in the recording. One of these is based on a Yemenite melody, while the other is an original setting of a 17th-century poem about the fraught and dangerous experience of diaspora. The Ladino language that Pomerantz values so highly is represented in the Three Sephardic Songs of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895–1968), who came from a centuries-old Sephardic family in Tuscany but emigrated to the United States to escape the Holocaust.

The wide range of experiences of diaspora figures, too, in the three Yiddish songs arranged by Sidor Belarsky (1898–1975), which include a setting of an expressive love song (“Papir iz dokh Vays”), a song about a miller chased away from his shtetl by violent pogroms (“Dem Milners Trern”), and a song — simultaneously mournful and hopeful — that longs for the ultimate redemption through the coming of the Messiah (“Zol shoyn kumin di Geule”). In all likelihood, the melody of that third song was originally composed by two musicians, Shmaryahu Kaczerginski and Abraham Sutzkever, who fought as part of the allied resistance after their families were murdered in the Vilna Ghetto during the Holocaust. The bittersweetness of the song — its lament over such horrifying losses and its continued insistence on hope for a better future — is captured with heart-wrenching expression in Pomerantz and Schenkman’s flexible, moving performance.

Two songs by Ilse Weber (1903–1944) demonstrate both the profound loss encompassed with the experience of the Jewish diaspora and the performers’ dedication to keeping this music alive. In 1942, the Czech-born Weber was interned at Theresienstadt, the Nazi concentration camp that also served as a vehicle of Nazi propaganda through its “permission” (more correctly, its compulsion) that its prisoners engage in cultural activities. During her imprisonment there, Weber produced some 60 songs and poems. Finally deported to the Auschwitz death camp in 1944, where she was murdered upon arrival, Weber is reported to have sung the lullaby “Wiegela” to her son on the way to the gas chamber. While the melody survives only in unaccompanied form, Pomerantz and cellist Sarah Freiberg, who plays on three tracks of the album, arranged the piece for voice and cello.

A striking aspect of Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora is its juxtaposition of musical settings of the same Yiddish poem — “Unter dayne vayse shtern” (Beneath the Whiteness of Your Stars) by Avraham Sutzkever (1913–2010) — by two composers. The first setting is by Lazar Weiner (1897–1982), whose family fled Ukraine following the notorious Beilis blood libel of 1914, and who made his home and career in New York. Known as the “father of Yiddish art song,” Weiner sets Sutzkever’s poem as a means of conveying what Pomerantz describes as “the helplessness that Weiner and many North American Jews felt in the face of the genocide in Europe” during the Holocaust. The second setting of Sutzkever’s poem is by American composer Lori Laitman, who was born in 1955. Laitman’s song was written for a commission by Music of Remembrance as part of the cycle The Seed of Dream.

For Pomerantz, this juxtaposition was essential to capture the developing arc of Jewish history and its music. “You get Lazar Weiner setting ‘Unter dayne vayse shtern,’ and then you get a contemporary Jewish composer [Laitman], who lives not five miles from me, interpreting the same text and snippets of the same melody,” he said. “This is part of her modern Jewish identity, and it shows how she relates to her Jewish past and her family’s experience while also looking forward to a Jewish future in the United States and a Jewish compositional voice that is uniquely modern — and uniquely her.”

This idea of a compositional voice led me to ask Pomerantz and Schenkman what made the music on this recording “Jewish.” Schenkman began by problematizing the question: “What does it mean to sound Jewish? A lot of us grew up with the idea that ‘sounding Jewish’ means sounding like Fiddler on the Roof.” This was a notion that Schenkman sought to unsettle. In selecting his solo piano pieces for the recording, he turned to Joel Engel (1868–1927), born in Ukraine and educated at the Moscow Conservatory. Engel’s “Nigun,” from Five Pieces for Piano, Op. 19, clearly reflects his interest in Jewish folk music (the word “nigun” is Hebrew for “melody”). Yet his Mazurka in F-sharp Minor, from the Three Pieces for Piano, Op. 12, does not bear an obvious connection to a uniquely Jewish musical tradition. “But,” Schenkman wondered, “is the Nigun more Jewish than the Mazurka? I don’t know.”

He continued by noting that, in every performance he gives, “I am playing my experience. That means it’s American, it’s Jewish, it’s queer. It has my thumbprint. It goes back to how multifaceted the idea of being Jewish is. Intergenerational trauma is part of the Jewish experience, but it’s not the Jewish experience. Studying Torah is part of the Jewish experience, but it’s not the Jewish experience.”

Schenkman continued, “The fact that we’re interested in exploring what it means to be Jewish, what it means to have an established repertory of art song, and who decided what that was, whom it is for, and whose experience it reflects — in a way, those all seem to me like very Jewish explorations. They are analogous to the way we would discuss what a passage of the Torah means to us now compared with what it meant for [the Medieval Jewish commentator] Rashi or anyone else.”

For his part, Pomerantz seeks to avoid essentializing ideas of Jewishness. As he discussed in a personal essay published by EMA in 2022, “Let’s Talk About Antisemitism in Our Field,” he has been subjected by members of the early-music community to demeaning stereotypes that cast him as incapable of escaping an essentially “Jewish sound.” Pomerantz’s experience resonates with what musicologist Ruth HaCohen has called the “music libel against the Jews” — a centuries-old belief that Jews are sonically and socially disruptive, and ethically incapable of making true music. In our conversation, Pomerantz recalled having been told by a German singing coach that “no matter what sound I make, it will sound Jewish because of my racial physiology and anatomy. I walked out.”

Thus, rather than seeking an essentially “Jewish sound” in selecting the music for Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora, Pomerantz looked for works in which composers “were expressing their Jewish identity through music and poetry. That’s what makes it Jewish.”

When Pomerantz and Schenkman began work on this project in 2017, antisemitism had already been on the rise in the United States and worldwide. Since Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the start of the resulting war, there has been an alarming surge in antisemitism — including in the academic and artistic circles in which Pomerantz, Schenkman, and I travel — and all three of us have experienced this new antisemitism in direct ways. We talked about the significance of Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora in this context.

A kippah is a multifaceted symbol but the problem with symbols in today’s social media age is that they lose nuanced meaning

Schenkman called attention to the problematic way in which people frequently conflate Jewish identity with today’s geopolitics. “People interpret my wearing a kippah [a Jewish head covering] as meaning certain things: you’re on one team or the other,” he said. “But it’s more complex than that.” A kippah is indeed a multifaceted symbol: The problem with symbols in today’s social media age is that they lose nuanced meaning.

One colleague advised Schenkman to avoid performing Jewish music while the war between Israel and Hamas is ongoing. “Oh,” he asked rhetorically, “because of something that’s going on politically, I should deny my heritage and my identity and steer clear of cultural riches?” He continued, “It’s weird to hear that kind of thinking from people who would say it’s fine to perform Bach’s St. John Passion” — a work that projects a clear anti-Jewish bias — “because it’s great music by a great composer, and the political implications are not relevant. There’s a double standard there.”

An album about the persistence of memory

Pomerantz concurred. “I have never felt so proud and yet so scared to be publicly Jewish,” he said. “I wake up almost every day to some sort of harassing message, because I am so public about my Judaism, including in my promotion of this album. Last week I had students who left an ensemble that I was coaching because they refused to perform the music of [17th-century Jewish composer] Salamone Rossi. They thought it was a problem because of the modern political conflict. For me, this is exactly why this music needs to be performed. Many of the composers on our recording faced similar intimidation to what Jewish musicians are facing right now. I want to be unapologetically, musically Jewish — I am an unapologetic musical Jew. The antisemitism that we are seeing now is not new. Jews have been in similar historical circumstances well within living memory. So this album is partly about the persistence of that memory.”

Despite these troubling circumstances, Pomerantz closed our interview by affirming that this album is not just about the lachrymose narrative of Jewish history. Rather, he explained, “I went into this project with the understanding that Jewish song is more than a rehashing of trauma. It is music of great joy, of resilience, and at times of defiance: songs written by partisans in the woods who were not sure if they were going to wake up the next day, songs about a young man standing outside his beloved’s door, songs about living life as any other person would. These are moments of joy and celebration and everything else that goes into the living of a full life.”

Indeed, Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora offers a compelling account of the full range of human experiences and emotions. Listeners seeking a musical encounter that is deeply researched and historically informed, performed with undeniable insight and expression, and edifying in its emotional arc and storytelling would do well to spend time with this remarkable album.

Rebecca Cypess is Mordecai D. Katz and Dr. Monique C. Katz Dean of the Undergraduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Yeshiva University. Her recent publications include Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment (2022) and she co-edited the collection Music and Jewish Culture in Early Modern Italy. A historical keyboardist, Cypess is the founder and director of the Raritan Players. Among her writings for EMA is an article about women composers in the early modern world, Asserting Her Voice: Angélique Diderot, keyboardist and composer.