by

Published August 10, 2018

Leipzig After Bach. Jeffrey S. Sposato. Oxford University Press, 2018. 313 pages.

By Valerie Walden

BOOK REVIEW — The image on the cover of this book features a piano being thrown out of an upstairs window. This might lead the reader to think that perhaps the Leipzig musical scene post-1750 was tumultuous. It wasn’t. Leipzig After Bach portrays a stolid, middle-class German city, comfortable in its relatively conservative religiosity and intellectualism, which moves gradually through the cultural issues posed by the Enlightenment into a world easily recognizable to those of us who attend both church and musical entertainments.

After a clear and comprehensive introduction, the first chapter documents in rich detail how Leipzig’s 18th-century theologians zealously guarded Luther’s teachings, the connections between politics and music performance, and why Lutheranism and Catholicism remained so closely integrated, the continued reliance on Catholic traditions by Lutherans being anything but rebellious. According to Jeffrey S. Sposato, this orthodoxy had a significant effect on the music offered to Leipzigers, who, unique from other German citizens, saw music as “an essential element in the service to God… a pillar of public concert life.”

After a clear and comprehensive introduction, the first chapter documents in rich detail how Leipzig’s 18th-century theologians zealously guarded Luther’s teachings, the connections between politics and music performance, and why Lutheranism and Catholicism remained so closely integrated, the continued reliance on Catholic traditions by Lutherans being anything but rebellious. According to Jeffrey S. Sposato, this orthodoxy had a significant effect on the music offered to Leipzigers, who, unique from other German citizens, saw music as “an essential element in the service to God… a pillar of public concert life.”

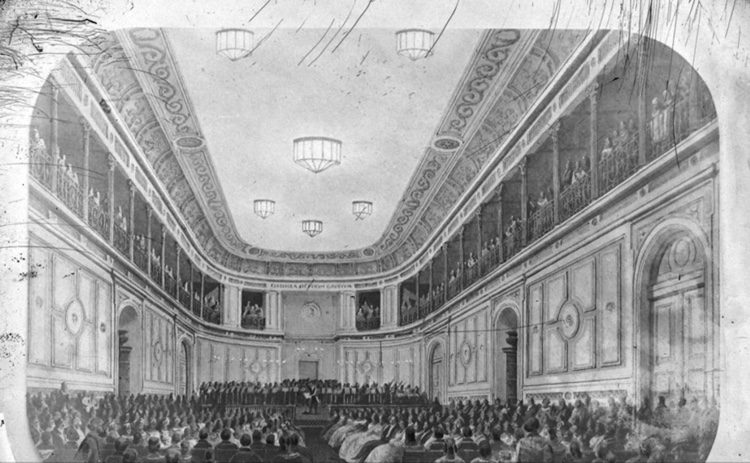

The remaining three chapters delve into the relationship between Leipzig’s sacred and secular musical experiences. Sposato describes the idiosyncrasies of the Leipzig musical establishment, one created by the existence of a vibrant middle class that desired quality music, but lacking an aristocratic establishment to help support sophisticated music making, especially opera. This led to a reliance on subscription-concert societies, the book examining their history, membership, and programming, as well as the interactions between the church musicians, university students, and town musicians who provided the city’s performances.

Although the emphasis of the second chapter is on the years 1743-1785, Sposato lays the groundwork with a concise history of earlier secular musical groups, their programs, and their notable directors, such as Telemann, Kuhnau, and Bach. In tracing the influence of the town’s sacred music on its emerging secular institutions, the author delineates how the performance of cantatas was gradually replaced by polyphonic mass settings chosen by Bach’s successor, Gottlieb Harrer.

Further changes were instigated by J. F. Doles and J. A. Hiller, who, in turn, assumed the position of Thomaskantor — Doles from 1756-1789 and Hiller from 1789 to 1804. As Sposato explains, “Hiller’s multifaceted engagement with sacred music had a substantial impact on his more well-known work on reviving Leipzig’s public concert life.” Actively involved with the secular Grosse Concert and Musikübende Gesellschaft, Hiller founded the Gewandhauskonzerte in 1781 before taking the position that had been Bach’s, Sposato offering a fascinating account of how at that time, the secular programming of the Gewandhaus concerts was based on the Lutheran liturgy.

The third chapter examines the work of Hiller and his successor, Johann Schicht, as Thomaskantor from 1810-1823, a period during which Leipzigers’ lives were thrown into disarray by the events of the Napoleonic Wars. The disorder caused a continuous decline in church attendance that, according to Sposato, forced those responsible for music to create a church service that was “engaging, edifying, and spiritually moving.” This section is particularly valuable for anyone interested in becoming better acquainted with Hiller and Schicht.

For most of us, the first name that comes to mind when discussing post-Bach Leipzig is Felix Mendelssohn, the focus of the book’s final chapter, which not only examines the political intrigue that accompanied Mendelssohn’s hiring, but also the resulting changes in music selection that resulted from his tenure. This is also a study in the modernization of programming, Sposato making the point that Leipzig’s 19th-century audiences differed little from today’s.

As with contemporary music directors, Mendelssohn had to find a balance between lighter, popular works and longer, more intellectually conceived pieces. He also initiated a trend very recognizable to today’s audiences: performing the works of Baroque musicians, a feature that may have been inspired by his teacher and future Leipziger, Ignaz Moscheles, who was presenting similar repertoire in London. Sposato also makes the interesting point that under Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus, the simplification and shortening of the Lutheran church service resulted in the concert hall becoming the venue for the performance of longer church works. This fact influenced the writing of sacred works for the concert hall by Mendelssohn and others, their compositions therefore featuring a larger orchestra and a more symphonic sound.

The illustrations, musical examples, and tables in Leipzig After Bach are excellent and well integrated with the text, adding much to amplify the scholarly material presented. However, this is not a book written to entertain the reader. The prose is stilted and rather repetitive, with the phrase “as noted” used far too frequently. Nevertheless, Sposato has carefully constructed a narrative that threads together a wealth of political, social, and musical history, bringing clarity to a topic deserving of such attention.

Valerie Walden is the author of One Hundred Years of Violoncello: A History of Technique and Performance Practice, 1740-1840; a chapter in The Cambridge Companion to the Cello and Reader’s Guide to Music; and 31 entries in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. She is preparing an edition of the music of the noted 19th-century London cellist Robert Lindley for Bärenreiter.