Stephanie Noori makes her living playing baroque violin and viola and viola da gamba. Typically, she has at least one concert a week on her calendar. But in a matter of days in mid-March, months of engagements evaporated.

“Up until this point, I don’t think you ever consider that all of your performances, all of your work could just be gone at one time, particularly because it comes from so many different sources,” said Noori. “So this is the first time I’m experiencing a true job loss across the board.”

Like millions of other Americans who find themselves without work because of the shutdowns and restrictions related to the coronavirus pandemic, she is wondering: What’s next? Luckily, the Denton, TX, musician and her husband, a theorbo player, had recently been stockpiling savings.

“So when this happened, we were like: We can survive a few months without having income,” Noori said. “It’s not ideal, but we’ll be OK.”

But thousands of others aren’t so fortunate. Musicians have been hit especially hard financially because many are “gig workers,” freelancers who earn money concert by concert and cannot count on full-time salaries or benefits such as health insurance.

Period performers arguably are particularly vulnerable, because early music is a specialized field with fewer opportunities to begin with. And many of the festivals and ensembles such musicians play for are smaller and more financially fragile than their larger counterparts in the mainstream classical world.

Equally or perhaps even more painful than the financial pain from coronavirus quarantines is what Liza Malamut, a Boston-based historical trombone player, calls the “spiritual loss” from not making and sharing music.

“I’m an ensemble player,” Malamut said. “I’m not a soloist. Part of the reason I love playing the trombone is that I get to play with other people, and I really miss doing that. We’re not always aware of that sort of fulfillment, because it’s just part of our everyday jobs, but when it’s taken away, suddenly it becomes this big thing that is gone.”

Losing such musical fellowship is especially difficult, agreed Carla Sciaky, a violinist in the Denver-based Baroque Chamber Orchestra of Colorado. “The money part is huge,” she said, “but the soul-filling part of being able to play together and come together — that’s what we’re all hooked on.”

Some musicians have other jobs or a spouse’s income they can fall back on. Countertenor Jay Carter lost all of his engagements around Easter, usually a busy time for him, and nearly all summer appearances at festivals like the Portland (Maine) Bach Experience have been canceled. But he continues to work as an assistant professor at the Westminster Choir College at Rider University in Princeton, NJ, teaching remotely via the online platform Zoom. “So the loss of those [singing engagements], while a significant blow to my income, is not quite so crippling as it is for my colleagues who do nothing but freelance,” he said.

Soprano Cassandra Extavour, who sings with the Boston-based Handel and Haydn Society, among other groups, also leads a biological research laboratory at Harvard University. Although it is shut down because of COVID-19 restrictions, she is still drawing her salary. In addition to his 20-30 freelance engagements a year, cellist and viola da gamba player Craig Trompeter serves as artistic director of the Chicago-based Haymarket Opera Company, which focuses on 17th- and 18th-century works. The organization has canceled its spring activities but is still paying its small staff and preparing for upcoming seasons.

Soprano Jolle Greenleaf is artistic director of New York’s TENET Vocal Artists, which has canceled all of its events through early fall, including a performance of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. She has had to put her salary on hold, in addition to losing the fees from canceled freelance performances, but her family has been able to get by on the income from her husband’s job in the tech field.

But many musicians don’t have such financial cushions. Among them is Malamut, who has little choice but to get help through Pandemic Unemployment Assistance. Although the temporary federal program offers 39 weeks of unemployment benefits to freelancers not usually eligible for such help, getting registered has proven challenging. “Obviously, the bulk of my income is through performance,” Malamut said. “Everyone is kind of dealing with it, but it’s not easy, and I’m definitely hopeful that things will pick up when this is over.”

For now, period musicians are doing what everyone else is doing, hunkering down at home with their families and just trying to wait out the pandemic. For Greenleaf, who lives in New York City, the metropolitan area hardest hit by COVID-19, it has not been easy. “I think the biggest challenge in New York is just that there are so many people who live here,” she said. “People are really on top of each other, so there is a lot of fear around basic safety issues and concerns about health.”

Still, these musicians are trying to make the best of the situation, and even find positives amid the gloom. They are using this extra time to catch up on overdue practice or finally get to a book in their field they have wanted to peruse. “We’re suffering, of course,” Trompeter said, “but in some ways, we have the time to reconnect with our instruments better and do a lot of reading. It’s actually been for me a very fruitful time.”

Other musicians have found ways to perform despite the elimination of formal concerts. Sciaky, the Colorado baroque violinist, is also a folk musician, and she sets up an amplifier and performs what she calls “driveway concerts” in that genre for neighbors in her Denver suburb who gather outside and follow proper social distancing.

Noori is hosting a series of weekly online lunchtime concerts via Facebook. It is organized by Lumedia Musicworks, a Dallas-based early-music group for which she serves as instrumental director. “Because if we can’t have performances for a while,” she said, “and you want to stay in the public eye and your audience’s eye somehow, and you want to be somewhat relevant, then the question is: How do you engage with your audience in a meaningful way online?”

Extavour, the Boston soprano, believes some lessons might even come out of this bizarre time that musicians can use later. One of her final concerts was a March 6 performance of Mozart’s Requiem that at the last minute had to be live-streamed because of just-instituted restrictions on gatherings of 100 or more people.

Audience members were able to make comments online as the event was happening — connecting with each other and musicians in a way that is not typically possible. Extavour wonders if there isn’t a way to make such interaction a part of conventional concerts. “There is something that could be gained in the future from what is now a forced virtual experience,” she said. “It doesn’t need to replace live performance, which we will get back to, but it could augment it.”

Most of these musicians believe they can get by now and maybe through the end of the summer, but what happens if the shutdowns and cancellations go into the fall or even beyond? After all, how many people are going to want to return to concert halls if the threat of the virus hangs in the air, literally and figuratively?

“I think it’s a big question mark for everybody right now,” Malamut said. “It’s going to depend a lot on what happens with the virus. It’s going to depend on the financial stability of the organizations that hire musicians as a result of what happened this summer.”

Beyond applying for unemployment benefits, some musicians are contemplating getting temporary jobs in other fields, but those will be hard to find during the economic crash that has accompanied the COVID-19 crisis. Others are turning to what Noori, the Texas string player, called “side hustles,” which in her case consists of web design and greeting cards she sells online.

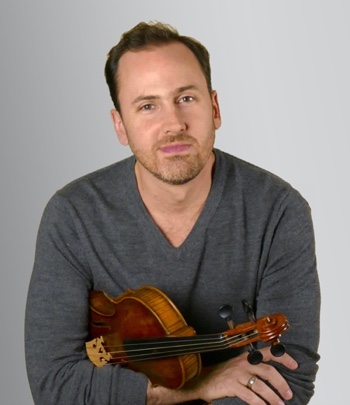

Violinist Adam LaMotte, a member of the Portland Baroque Orchestra and artistic director of the Montana Baroque Festival, has a small business selling stringed instruments and does some private teaching. He and his wife have received a mortgage forbearance and can get by for the moment.

“I fear for September-October time,” he said. “If this continues, then I don’t know what we can do.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.