by John Ahern

Published August 14, 2023

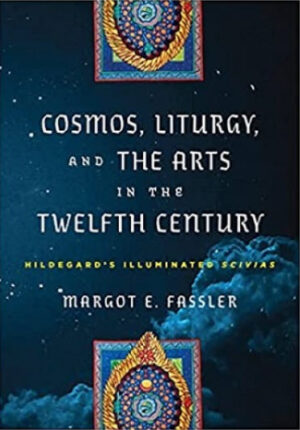

Cosmos, Liturgy and the Arts in the Twelfth Century: Hildegard’s Illuminated Scivias by Margot E. Fassler. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022. 392 pages.

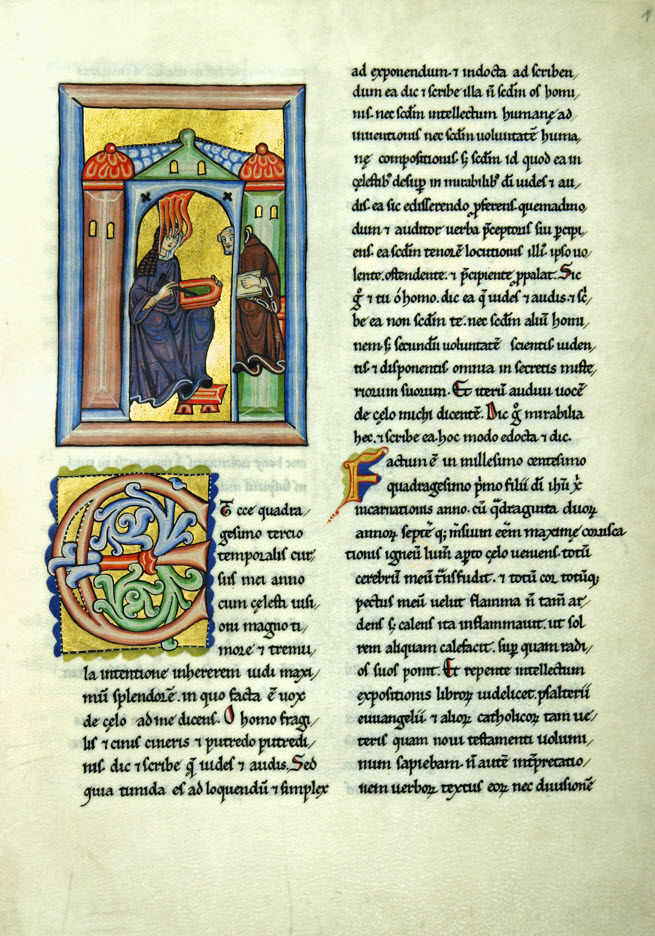

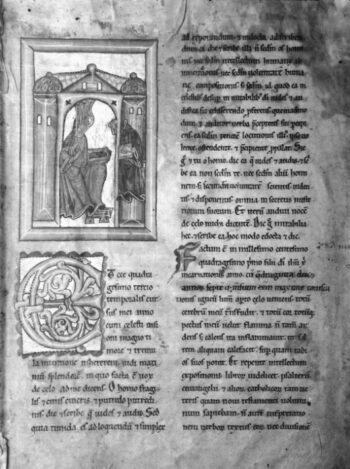

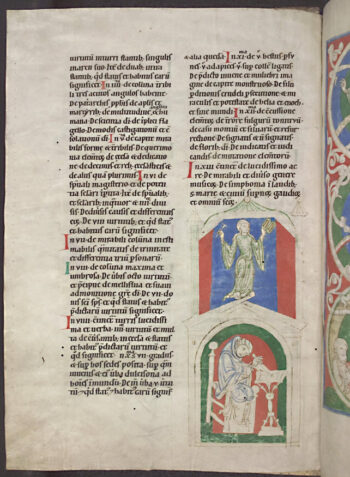

In 1945, in the midst of the firebombing of Dresden in World War II, a major manuscript containing an illuminated treatise by Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias (or Know the Ways) went missing. It has not been seen since. It was only owing to the uncanny foresight of some unknown community of artists that a hand-illuminated manuscript copy was made and is now still preserved in the religious community of the Abbey of St. Hildegard, Eibingen.

Exactly how this copy manuscript came about remains a mystery to scholars. But we are also very fortunate to have black-and-white images of the original against which we can compare the hand-made color copy in order to determine how close it comes to the source. It is, as it turns out, an extremely faithful copy of the original manuscript and its illuminations.

Exactly how this copy manuscript came about remains a mystery to scholars. But we are also very fortunate to have black-and-white images of the original against which we can compare the hand-made color copy in order to determine how close it comes to the source. It is, as it turns out, an extremely faithful copy of the original manuscript and its illuminations.

All of this means that a 21th-century audience has only narrowly been given an opportunity to peer through this crucial window into Hildegard’s work and thought. We are in debt to Margot Fassler, who demonstrates in Cosmos, Liturgy, and the Arts in the Twelfth Century that Hildegard was personally involved in the creation of this manuscript of her theological treatise Scivias. From historical accounts and evidence in the images of Scivias, Fassler shows that although Hildegard likely did not herself paint the illustrations, she likely worked in person with scribes to create the images. Fassler’s book has therefore provided a visual and sonic entry point into the Hildegard’s 12th-century world.

Hildegard’s treatise Scivias recounts her visionary conception of redemptive history, from the six days of creation to the spheres of the heavens, to Adam’s fall and the “edifice” of salvation in Christ, ending in the apocalyptic joy of new creation. Along the way Fassler interprets a few of Hildegard’s eccentric illuminations, such as the “cosmic egg” (pictured on the dust jacket) and the Godhead sucking the light from Lucifer and his followers, conceptualized as stars. Fassler argues that the whole work is structurally and thematically organized by the liturgy for All Saints Day (November 1) in particular, showing how closely liturgy and cosmos were connected in Hildegard’s community.

Hildegard’s theology takes on cosmic proportions and moves, seamlessly and mystically, from daily life into heavenly reality. How such a motion from microcosm to macrocosm takes place, Fassler argues, is through liturgy. It is the sung prayers and rituals of Hildegard’s religious community that prompt worshippers to realize the cosmic significance of each of their mundane actions. For Fassler, Hildegard’s goals went boldly beyond even this: Through worship, the Christian actually transforms the world, purifying it and hastening its consummation in the new heavens and new earth.

It is this grand mission which, for Fassler, forces Hildegard to employ every possible medium available to her. The Scivias that Fassler describes was a multimedia work. It did not limit itself merely to the written word but included visual aid and song as well. “The imagistic understanding that Hildegard has constructed through her treatise, her lyrics, her music, and the accompanying artworks provides a sense of how the media in which she worked were meant to inform the imaginations of women in her community and provide their various struggles and lives with cosmic dimensions.”

Prose and poetry were not sufficient to capture the harmony of the cosmos which Hildegard witnessed in her visions; only vibrant color, allegorical representation, diagrammatic science and, most of all, the chants.

Fassler’s sensitivity to Hildegard’s chants in Scivias is what makes this book a unique contribution in the field. Hildegard’s vocal lines are famously quite different from the Gregorian chants which they would have been heard alongside.

The latter chants tended to move in stepwise motion with only occasional leaps, usually occupying a range of under an octave. Hildegard’s compositions seldom missed the opportunity to wander far beyond the octave, often covering the span of a ninth in just a few notes. Few scholars can move as quickly from the intellectual history of neo-Platonism to the details of the musical score and back again. But in the wild, wide range of Hildegard’s vocal lines Fassler shows the very action of prayer which encompass and renew the whole cosmos.

Fassler’s book is a summation of her years of work on Hildegard. It is only occasionally technical — both musically and in its careful study of the manuscripts and their construction — but spends most its time working through Hildegard’s aesthetics and theology in accessible and engaging prose. The book meanders delightfully through its material and, if there is any fault, it is simply that it leaves its reader overwhelmed and bewildered by the richness of the connective tendrils running out in every direction. It is a fitting way for the book to be, reflecting as it does the Scivias itself: at once mystical, vivid, all-embracing, sharply outlined, and highly original.

John Ahern is a Ph.D. candidate writing a dissertation on the masses of Fremin le Caron and the evolution of contrapuntal style in the 15th century. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and family.