by

Published July 27, 2018

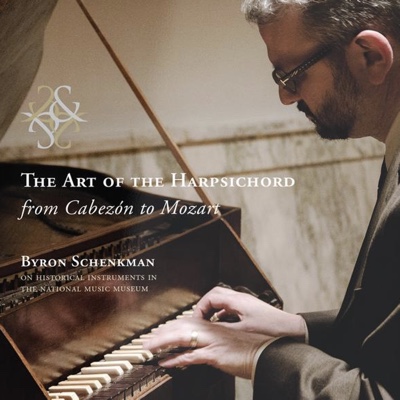

The Art of the Harpsichord from Cabezón to Mozart

Byron Schenkman on historical instruments in the National Music Museum

BSF 171

By Daniel Hathaway

CD REVIEW — Seattle-based keyboardist Byron Schenkman has more than 30 CDs of 17th- and 18th century music to his credit, some involving period instruments from the collections of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and the National Music Museum in Vermillion, SD. His recent recording, The Art of the Harpsichord from Cabezón to Mozart, released on his own label, features performances on eight instruments in the vast Vermillion collection.

The museum was founded in 1973 on the campus of the University of South Dakota as the “Shrine to Music Museum,” originally incorporating some 2,500 instruments acquired by Arne B. Larson, a high-school band and orchestra director and piano tuner. He traded tea and Spam with British collectors in exchange for antique instruments during World War II, used them to present programs throughout the upper Midwest, and gained national recognition as a guest on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. After becoming professor of music at USD, he donated his trove of instruments to the university. Now greatly expanded with a collection of more than 15,000 instruments, the National Music Museum is known internationally as a center for musical instrument scholarship.

The museum was founded in 1973 on the campus of the University of South Dakota as the “Shrine to Music Museum,” originally incorporating some 2,500 instruments acquired by Arne B. Larson, a high-school band and orchestra director and piano tuner. He traded tea and Spam with British collectors in exchange for antique instruments during World War II, used them to present programs throughout the upper Midwest, and gained national recognition as a guest on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. After becoming professor of music at USD, he donated his trove of instruments to the university. Now greatly expanded with a collection of more than 15,000 instruments, the National Music Museum is known internationally as a center for musical instrument scholarship.

On this album, Schenkman demonstrates five of the museum’s 12 harpsichords and both of its spinets (the collection also includes three virginals). He writes in the liner notes: “I wanted to provide a means to hear all these instruments side by side with as much kept constant as possible: the same harpsichordist, same engineer, and same room…I also wanted to fit the repertoire as closely as possible to each instrument.”

Those instruments cover a span of more than 250 years, from an anonymous, 45-key Neapolitan harpsichord (ca. 1530) to a Kirckman double with machine stops and a Venetian swell (not used on this recording) built in London in 1798. The repertoire, as promised, ranges from Antonio de Cabezón to Mozart (though actually a bit later, thanks to a Haydn sonata). In between, Schenkman explores harpsichords by Giacomo Ridolfi (ca. 1675, via a Toccata and Passacaglia by Johann Kaspar Kerll), José Calisto (Portugal, 1780, his only known instrument, featured in Domenico Scarlatti sonatas), and Jacques Germain (Paris, 1785, used for pieces by Jacques Duphly, Michel Corette, and Mozart).

Schenkman changes things up with tracks featuring two spinets. Little pieces by Purcell are perfect for an instrument by Charles Haward (London, 1689), and his choice of works for a Johann Heinrich Silbermann spinet (Strasbourg, 1785) include a piece by the builder himself, as well as a C.P.E. Bach sonata. The only known octave virginal to be built by Onofrio Guarracino (Naples, 1694) is the vehicle for a Toccata and Passacaglia by Gregorio Strozzi. All the instruments except the Silbermann spinet are outfitted with bird-quill plectra.

Schenkman’s performances of this well-chosen, varied, and in some cases unusual repertoire are fluent, idiomatic, and engaging. Recorded over the course of a week in the museum’s Arne B. Larson Auditorium, they benefit from sensitive engineering and editing by Peter Nothangle. An illustrated booklet with full descriptions of the harpsichords and spinets by USD professor emeritus John Koster tells you all you could possibly need to know about the rich history of these instruments.

The album may also inspire visits to the museum by those who haven’t yet made a pilgrimage to South Dakota. In that case, be advised that the NMM will be closed to the public after October 6, 2018, until sometime in 2021 for architectural expansion.

Daniel Hathaway founded ClevelandClassical.com after three decades as music director at Cleveland’s Trinity Cathedral. He studied historical musicology at Harvard College and Princeton University, and orchestral conducting at Tanglewood, and team-teaches Music Criticism at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.