by Karen M. Cook

Published May 8, 2023

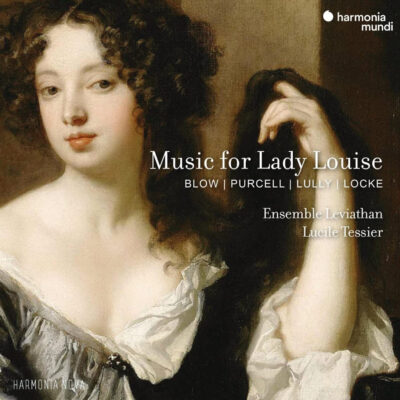

Music for Lady Louise: Blow, Purcell, Lully, Locke. Ensemble Leviathan, led by Lucile Tessier. harmonia mundi HMN916119

While not a household name today, the French-born Louise de Penacoët de Kéroualle was a central figure in 17th-century high society. By 1673, she was the main mistress of Britain’s King Charles II, who had given her several illustrious titles, including Duchess of Portsmouth. Not incidentally, she was employed by Louis XIV as an informant and to help keep the English court under the Sun King’s influence. Louise remained Charles’ mistress until his death in 1685.

But Louise was not Charles II’s only fascination with France, before and after her arrival. He was long enamored of French music, employing French musicians and sending English composers and actors abroad to study, and had even set up his own version of his cousin Louis XIV’s famed 24 Violins. Louise had her own musical establishment at Charles’ court and often hosted the king for concerts—which gave the French musicians opportunities for espionage. Such event would have featured excerpts from French operas and other stage works by French and English composers, and of course instrumental music, since French woodwinds were all the rage in England at the time. And all are featured here, on Ensemble Leviathan’s remarkable debut, led by Lucile Tessier, a recorder player, Baroque bassoonist, and musicologist.

The album is divided into four parts: Rustick Music, Soft Music, Mad Songs, and Mourning Songs. John Blow’s “Come shepherds all” opens the recording with a charming pastoral scene, followed by Lully’s vivacious “Air pour les pêcheurs” from Alceste. The recorders shine on the latter work and are in fine form on Purcell’s “Hornpipe” and Blow’s “Tune for flutes.” The oboe and bassoon also get their moments: Lully’s “Bourrée” is charming, while the bassoon is delightfully off to the races at the change of tempo in his “Que ces gazons sont verts,” which opens the Mad Songs set. And the entire instrumental ensemble shows their mettle in Matthew Locke’s energetic “Lilk” from The Tempest.

The album is divided into four parts: Rustick Music, Soft Music, Mad Songs, and Mourning Songs. John Blow’s “Come shepherds all” opens the recording with a charming pastoral scene, followed by Lully’s vivacious “Air pour les pêcheurs” from Alceste. The recorders shine on the latter work and are in fine form on Purcell’s “Hornpipe” and Blow’s “Tune for flutes.” The oboe and bassoon also get their moments: Lully’s “Bourrée” is charming, while the bassoon is delightfully off to the races at the change of tempo in his “Que ces gazons sont verts,” which opens the Mad Songs set. And the entire instrumental ensemble shows their mettle in Matthew Locke’s energetic “Lilk” from The Tempest.

These instrumental works are interspersed among vocal works from the operatic and theatrical stages. “In these sweet groves,” another by Blow, is a liltingly lovely conclusion to the Rustick set. A favorite of Charles, Lully’s beautiful “Dormons, dormons tous” from Atys, appropriately begins the Soft Music segment; the longest work on the album, it contrasts nicely the shorter, faster-paced works preceding it. Some levity is interjected in the anonymous “De foolish English nation” and in Samuel Akeroyde’s “A new song sung by a fop newly come from France.”

Soprano Eugénie Lefebvre shines on Purcell’s “See, even Night herself is here” from The Fairy Queen, while bass David Witczak spins a masterful tale in another of the Mad Songs, the anonymous “Forth from the dark and dismal cell.” Purcell’s “Prepare, the rites begin” nicely showcases all of the men’s voices, while the entire vocal ensemble is beautifully blended in Lully’s gripping “Ciel! Quelle vapeur m’environne.” Blow’s “Hark! How the lark and linnet sing” is not only a solemn tribute to Purcell on his death but a fitting bookend to conclude the album.

Given its intent to creatively imagine one of Lady Louise’s concerts at Charles II’ court, the album invites a certain intimacy, a sense of being in the front row to a theatrical revue. The singers and instrumentalists alike perform with a liveness and litheness, a flair for the dramatic, that encapsulates what this kind of concert might have sounded like. As a program, it’s very well planned; as an album, it’s very well executed. I look forward with excitement to Ensemble Leviathan’s next project.

Karen M. Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is associate professor of music history at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.