by James A. Brokaw II

Published December 4, 2023

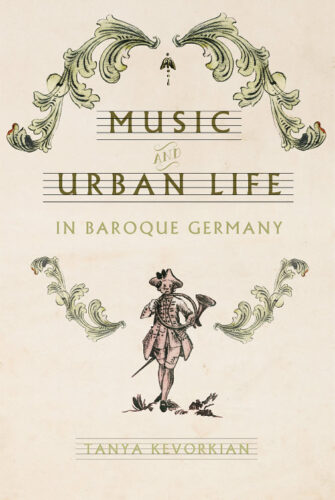

Music and Urban Life in Baroque Germany by Tanya Kevorkian. University of Virginia Press, 2022. 336 pages.

Over the past three quarters of a century, some of the most fascinating research in the world of classical music has come not only from studies of great composers and their works but from broader contexts of music making. Arthur Loesser’s Men, Women and Pianos, for example, is a social history of the keyboard first published in 1954 and still widely read. Or William Weber’s more recent The Great Transformation of Musical Taste, from 2009, which was actually the culmination of a series of studies over a half century that illuminated the evolution of concert programming, from a combination of popular and high art in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to the elite programs of the 20th, with their exclusive focus on intellectually demanding works by composers of the distant past.

More recently, Andrew Talle’s Beyond Bach: Music and Everyday Life in the 18th Century offers a fascinating illumination of the wider context of Johann Sebastian Bach’s works through the musical experiences of his fellow German citizens, centered around the keyboard instruments and their solo repertoire. Talle’s widely hailed effort has now found a worthy partner in Tanya Kevorkian’s fascinating and finely grained Music and Urban Life in Baroque Germany.

Where Talle focuses on keyboard instruments and their role in shaping domestic life, Kevorkian, a social historian, strives for a more wide ranging and broadly based depiction of musical life in five German cities, from 1650-1750, or roughly from the end of the Thirty Years War to the start of the Seven Years War. At issue are the southern cities of imperial Augsburg and the electoral seat of Munich, and the northern cities of Gotha, Erfurt and Leipzig. Munich was Catholic; Leipzig and Gotha were both Protestant, and Erfurt and Augsburg both had substantial Catholic as well as Protestant populations. By considering a wide spectrum of sonic phenomena in these different urban environments that might, depending on the listener, be perceived as “music” or “not music,” Kevorkian seeks to show how social distinctions and class were signified and reinforced. Even as she identifies the presumed strict boundaries of class, and bloodlines that defined 18th-century German society, she argues that those boundaries were far more permeable than they seem.

In her first chapter, Kevorkian begins at the pluralistic level of the street, and outlines changes in architecture and infrastructure over the period that intensified the resonance of city spaces, and introduces the watchmen, tower guards, vendors, and others whose sounds ordered urban life in Germany. Her second chapter focuses on the tower guards, crucial to daily timekeeping, examining their training, work and family lives; her third and fourth chapters are on town musicians, the guards’ “occupational cousins,” who played at “outdoor and indoor civic, ecclesiastical and celebratory occasions” and were central to forming urban culture.

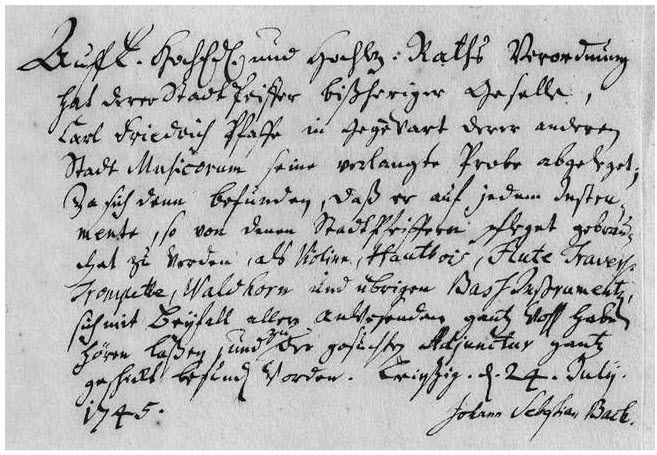

Here we find wonderful profiles of these men, their family lives, their guilds, their various ensembles, and the often keen competition between them, as well as their performance venues ranging from taverns and coffee houses to palaces and churches. Although Kevorkian cites a number of examples of watchmen’s calls and coachmen’s horn signals featured in the formal compositions of J.S. Bach, Sebastian Knüpfer, and others, her main concern is weaving a broad, comprehensive tapestry of the mundane sounds that created the “temporal rhythms” of urban civic life.

In her last three chapters, Kevorkian follows these men and women as they interact in a widening array of contexts. The fifth chapter examines weddings. Here Kevorkian details all components of the process: the negotiation of a contract between the families, the procession from home to church, and so forth. For the relatively few able to marry — property holders, merchants, artisans, and of course the elites — a wedding was the most visible marker of status and the most elaborate celebration of a lifetime. As such, wedding celebrations were heavily regulated by the authorities according to status of the celebrants: the number of guests permitted, the food consumed, and especially the music, its duration, and the number and types of performers. Multiple sources of tension attended these events, ranging from disputes with the authorities, disruptive crowds of onlookers at public processions, and competition between performing ensembles. Kevorkian traces these contours and conflicts in vivid detail.

The scope widens in the last two chapters. The sixth chapter examines music making in various spaces: on the street, in churches, and in opera houses. In her final chapter, Kevorkian considers interactions and musical relations between the urban populations she has already examined and villagers outside city walls, as well as with nobles who often visited or resided in cities. Erfurt and Augsburg, cities with substantial Catholic as well as Protestant populations, allow her to consider such interactions across religious affiliations as well.

Underlying the lucid prose of Kevorkian’s account is a rich fabric of painstakingly thorough archival research and a very broad array of secondary literature. She reads the data with a particularly compassionate eye, as seen in for example in her view of youth culture and street violence: “The authorities regarded youth activity on the street as a threat to public order and safety,” even as “the street presented a rare opportunity for socializing away from the watchful eyes of elders…Even historians who work hard to address street activity on its own terms have to some degree replicated the perspective of the authorities.”

Beginning early in the 20th century, we have seen increasingly successful efforts to recreate the sound of 17th- and 18th-century music, and we have become acutely aware of how vastly different this music is from the styles of the 19th and 20th centuries that once controlled the performance of early music. Kevorkian’s book is a valuable backdrop that provides new depth and dimensionality to our understanding of the music of Baroque Germany.

James A. Brokaw II completed a dissertation at the University of Chicago directed by Robert L Marshall in 1986. His English translation of Hans-Joachim Schulze’s Die Bach-Kantaten, a comprehensive survey of Bach’s cantatas, will appear in an abridged print and complete digital editions in Spring 2024 at University of Illinois Press and the Illinois Open Publishing Network.