by Anne E. Johnson

Published January 27, 2025

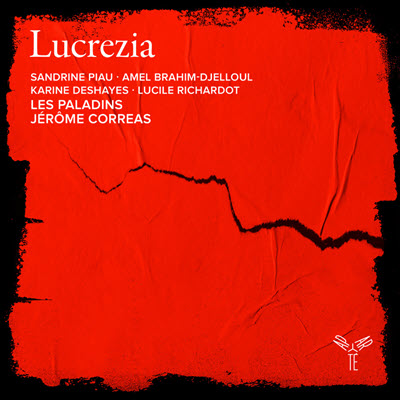

Lucrezia (Portraits of a Woman). Les Paladins directed by Jérôme Correas, with Sandrine Piau, Amel Brahim-Djelloul, Karine Deshayes, Lucile Richardot. Aparté AP359.

By legend, one of the world’s most powerful republics was born of violence against a woman. Roman historians recount how, around 508 B.C.E., a noblewoman named Lucretia was raped by Tarquin, prince of the Etruscans occupying Rome. When Lucretia killed herself to preserve her family’s honor, the enraged Romans paraded her corpse through the streets, inspiring a rebellion that turned their kingdom into a republic.

Lucretia’s riveting emotional voyage has inspired countless works of literature, painting, and sculpture, and fired the imagination of several Baroque composers, who crafted it into secular chamber cantatas, as intimate one- or two-character operas. Jérôme Correas and his orchestra Les Paladins have assembled all of the known versions together on one recording. Lucretia (or Lucrezia) now has an unprecedented chance to tell her story loud and clear — albeit through male composers.

Four cantatas exist on this topic: Michel Pignolet de Montéclair’s Morte di Lucretia, Alessandro Scarlatti’s Lucretia Romana, as well as G.F. Handel’s and Benedetto Giacomo Marcello’s versions, both simply called Lucrezia. Correas made the excellent decision to have a different singer portray Lucrezia for each work, helping to distinguish the representations of this intriguing character.

Soprano Sandrine Piau starts the proceedings as the title character in the Montéclair. Her singing of the aria “Dove vai, crudo spietato” has a darkness that maintains noble pride while skirting desperation. “Corragio mi spriti,” Lucretia’s pep talk to herself, is tight and energetic.

Lucrezia takes on a different tone in the hands of Scarlatti and soprano Amel Brahim-Djelloul. The performance and the music both launch into rage rather than starting in sorrow. “Barbaro hai vinto” seethes with fury. The structure of the work is distinct from the Montéclair, too, with recits, ariosos, and arias grouped into complex scenas that move within a spectrum of emotions, a preview of techniques that would become commonplace later in the century.

As the wronged lady in Handel’s version, soprano Karine Deshayes employs her rich voice to show her character’s strength and resolve. In her first aria, “Gia superbo del mio affanno,” she takes full vocal advantage of the composer’s surprising chromaticisms, letting them paint her character’s multifaceted emotional reaction to her situation.

Although Deshayes has a resonant low range, Lucile Richardot is the only mezzo-soprano among the four. The distinctive coloration that she brings to the Marcello cantata gives Lucretia a maturity appropriate to her heartbreaking responsibility. Richardot, a superb vocal actor, is especially compelling in the recitatives, where she demonstrates not only a naturalistic fluidity, but also great control over dynamics.

Named after the 1760 Rameau opera, the ensemble Les Paladins specialize in theatrical music. Their support of the singers, mostly as continuo, is thoughtfully and dramatically realized. Much of the accompaniment is played by Correas on organ, with the conductor also providing harpsichord for a secco sound.

The recording includes two instrumental works: Marcello’s Concerto a cinque, Op. 1, No. 7, and a sinfonia by Bernardo Pasquini. Both give Les Paladins an opportunity to step out of the pit, so to speak. With a few bowed-string players to enhance the continuo, the ensemble blossoms into a lively and carefully textured orchestra.

In his booklet essay, Correa credits the four composers with a “desire to give a voice through a musical composition to a woman who has suffered physical violence, and thus to explore her feelings.” Although he reminds listeners that, in the 18th century, Lucretia’s story was likely seen as “celebrating the sacrificial acts of a woman who thus redeems her own and her family’s honor,” the recording also reflects how “rape is, still, a topical issue.” As fine as these performances are, one can’t help but wish for the story to become obsolete.

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Book Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently wrote about celebrations for Palestrina’s 500th.