by Kyle MacMillan

Published October 14, 2019

The word “fun” is getting bounced around a lot as Chicago’s Haymarket Opera Company prepares its debut staging of John Frederick Lampe’s The Dragon of Wantley, a zany 18th-century send-up of Italian opera that also stuck it to politicians of the time.

“Whether it’s opera or whatever kind of classical music you’re doing, a fair amount of it’s pretty serious — deep human emotions that you are expressing,” said soprano Kimberly McCord, who sings the role of Margery. “This is not the case with Dragon of Wantley. It’s poking fun at some more serious social issues, but it’s doing it in a very light-hearted, Gilbert-and-Sullivan kind of way. You might even say that it’s Monty Python-ish.”

The Dragon of Wantley was Lampe’s biggest success, and it is his only opera to survive intact with recitatives and choruses. After debuting at London’s New Haymarket Theatre (also known as the Little Haymarket) in 1737, the piece became an immediate sensation. It transferred to Covent Garden, where it remained a perennial favorite through 1782 before falling out of view.

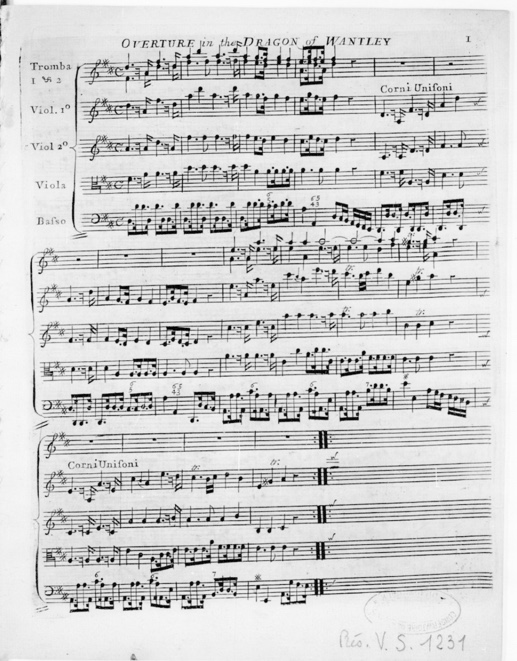

Viola da gamba player David Morris, the founder and musical director of the now-defunct San Francisco Bay Area baroque opera ensemble Teatro Bacchino, first mentioned the opera to Haymarket’s artistic director, Craig Trompeter, more than a decade ago. After hearing about the work from another friend, Trompeter decided to read more about it and obtain a score.

“I did that a couple of years ago and quickly realized it was a great piece,” he said. “I had to convince my board of directors to take a chance on it, because no one has heard of it, really. But the more I spend time with it, I’m just astounded that it doesn’t get done often, because it’s really funny and very approachable for audiences and performers alike.”

Haymarket Opera will present The Dragon of Wantley on Oct. 27 and 29 in Chicago’s Studebaker Theater, a historic 691-seat downtown venue that has become the regular home for Haymarket since reopening in 2016. The production will feature mostly company regulars, including Trompeter as conductor, Sarah Edgar as director, and all returning singers except for first-timer Michael St. Peter as Moore of Moore Hall.

Born in what today is the German state of Saxony, Lampe (1703-1751) moved to England in the 1720s and tried his hand at writing opera. But nothing really hit until he made his first foray into comedy in 1733 with The Opera of Operas, or Tom Thumb the Great. Lampe’s biggest success was The Dragon of Wantley. The libretto, written by one of the composer’s early associates in England, poet Henry Carey, was based on a well-known ballad with roots dating back to the Middle Ages.

The opera tells the story of a village being ravaged by a dragon in Carey’s native Yorkshire. The people turn to a nobleman, Moore of Moore Hall (St. Peter), who agrees to help on the condition that he receive the hand of Margery (McCord), a “fair maid of 16.” Naturally, that potential arrangement riles Moore’s ex-mistress, Mauxalinda (Lindsay Metzger). “The piece is enjoyable on its face,” McCord said, “without knowing any of the references, kind of like kids enjoy Rocky and Bullwinkle and adults enjoy it on another level.”

At the same time, the opera spoofs Italian Baroque opera, which was popular at the time in London. Handel’s Serse, for example, opened a year later. Lampe played bassoon in Handel’s orchestras and knew that musical world well. His comic gambit was to pair the florid emotionalism of Italian operatic stylizations with down-to-earth, at times vulgar English-language texts. “It’s this great juxtaposition of silliness and great music,” Trompeter said.

But that wasn’t all. According to JoAnn Taricani, chair of the music history program at the University of Washington in Seattle, there is a third, political layer to this opera, one that would have been readily apparent to 1730s London audiences. In the late 1990s, she prepared an edition of the opera for what was believed to be the American debut of The Dragon of Wantley by the Folger Consort, which is in residence at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Drawing on her continuing research of the work since, Taricani wrote the program notes for Haymarket’s production.

To understand the full dimensions of what she calls a “subversive political allegory,” it is important to realize that the Rump Parliament — a name meant to suggest a remnant Parliament after royal sympathizers had been purged — ordered the execution of King Charles I in 1649. That body was in turn overthrown by General George Monck in 1660, and Charles II reclaimed the throne. According to Taricani, hundreds of poems and ballads celebrated Monck and excoriated Parliament, with writers and cartoonists delighting in take-offs on the word “rump.” Monck was depicted as St. George slaying the dragon, which became a metaphor for Parliament. The original ballad of the dragon of Wantley fell right into this tradition, with Moore taking the place of Monck and the dragon getting killed by a kick to his — what else? — rump, a then-obvious allusion to the government.

It was no coincidence that The Dragon of Wantley opened at the New Haymarket Theatre, which was owned by Henry Fielding, a playwright so infamous for his political satire that a licensing law was passed in 1737, around the time of the opera’s premiere, in part to try to silence him. According to Taricani, Lampe and Carey had previously collaborated with Fielding, and the sharp-edged comedy in this opera was at least partly influenced by his writings.

Haymarket Opera is one of just three companies in North America devoted to presenting 17th- and 18th-century operas with both period music and staging. Edgar, a devotee of this historical approach, wants to bring as much physical comedy to this work as she can. “Because the words are so funny to begin with, the physicality of the singers needs to match,” she said as staging was about to begin.

To do that, she is consulting the same 18th-century acting treatises she normally does, texts that describe the restrained and artful positioning of the body. But since this is a comedy, she plans to stretch and exaggerate those movements in much the same way the grotesque dance style of the same era contrasted with the noble dance style. Because there is not as much written about the comedic style of that time, she will work more than usual from a contemporary perspective and then shape her ideas into a Baroque aesthetic.

Edgar is drawing on a host of sources, including silent movies for suggestions about slapstick effects. “I think about what my kids think would be funny,” she said. “I have a three-year-old and nine-year-old, so I’m really in touch with all the scatological humor.” She even consulted an episode of the 1980s television show Dynasty for guidance on how to stage a fight between the opera’s two female leads. “Movies have fights, but they are so physical that singers wouldn’t be able to do them, because it’s violent and you have to sing at the same time,” Edgar said. “But Dynasty had a great one.”

Like the music and stage direction, Haymarket Opera’s visual designs always have a period aesthetic, with sets that fold out like shutters or slide on runners. “Any time I do something mechanical, it’s with cranks or things like that,” said Evanston artist Zuleyka Benitez, scenic designer for the production. “We don’t use motors. We try to keep it as though it could have been produced at the time.”

Benitez is less interested in asserting her own artistic vision than perpetuating the visual aesthetic of the 18th century, when stock images represented, say, mountains or clouds. For inspiration, she looks to historical venues like the Drottningholm Palace Theatre in Stockholm, one of the few 18th-century European theaters with original stage machinery still in use.

But that doesn’t mean there won’t be distinctive scenic aspects to the production. “I’m making everything flat,” Benitez said. “The furniture is flat. The set pieces are all flat. So, if they (the characters) are drinking from a glass, the glass would be flattened. I’ve also changed the scale of objects to make them more comedic.”

And, of course, given the title of the opera, the big question is what the dragon will look like. “I tried to make him as funny as possible,” said Benitez. “The character that plays the dragon actually rides him as though it was a hobby-horse.”

Benitez knows that audiences come to opera primarily for the music and singing, but she believes it is important to give them something to look at as well. “Believe me,” she said, “when you go see this, the set is loaded. I have missed no opportunity to add ornament, to add a visual pun. And, of course, with Haymarket, if you don’t have a string of oversized link sausages somewhere in the production, it’s not Haymarket.”

According to Taricani, a presentation of The Dragon of Wantley typically takes place every year or so, usually by smaller companies in England or the United States. Trompeter is hoping that Haymarket Opera’s production will spark a mini-revival — a resurgence he believes this 282-year-old comedic romp deserves.

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.