by

Published December 22, 2017

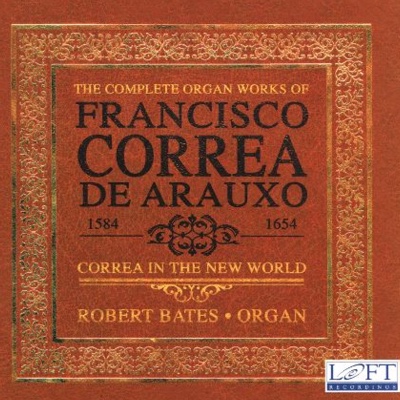

The Complete Organ Works of Francisco Correa de Arauxo (1584-1654): Correa in the New World.

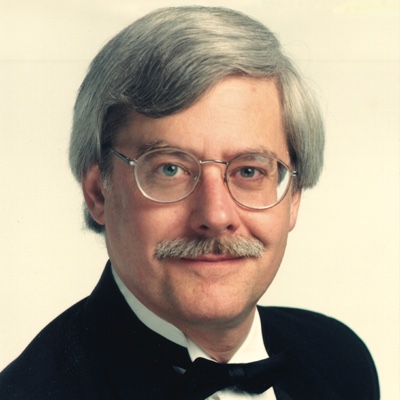

Robert Bates, organ.

Loft Recordings LRCD—1141-45

By Daniel Hathaway

CD REVIEW — Spanish organs of the 17th and 18th centuries are special beasts. Usually consisting of a single keyboard divided between middle C and C-sharp into treble and bass regions, each assigned their own registers, these instruments allow both for the performance of full-keyboard polyphonic works and pieces featuring solos in the right or left hand accompanied by contrasting stops in the other. Short octaves in the bass are the rule, and most of the time, the organs lack pedal claviers or feature only pull-down mechanisms for holding notes with the feet.

We have the priest-organist Francisco Correa de Arauxo (1584-1654) to thank for providing us with an extraordinary collection of music and theoretical information in his 1626 treatise, Facultad orgánica, and organist Robert Bates to thank for undertaking the enormous task of recording all the keyboard music in Correa’s anthology — just short of 70 individual pieces. In the five-disc set issued on Loft Recordings, Bates brings this elegant, sophisticated repertoire to life using five New World instruments — three restored historic organs in the Mexican province of Oaxaca and two modern instruments built in the Hispanic style in Northern California.

We have the priest-organist Francisco Correa de Arauxo (1584-1654) to thank for providing us with an extraordinary collection of music and theoretical information in his 1626 treatise, Facultad orgánica, and organist Robert Bates to thank for undertaking the enormous task of recording all the keyboard music in Correa’s anthology — just short of 70 individual pieces. In the five-disc set issued on Loft Recordings, Bates brings this elegant, sophisticated repertoire to life using five New World instruments — three restored historic organs in the Mexican province of Oaxaca and two modern instruments built in the Hispanic style in Northern California.

The Mexican organs include the 1712 Chávez instrument in Oaxaca Cathedral, the 1792 Neri y Carmona organ in Santa María de la Asunción, Tlacolula, and the anonymous, ca. 1729 instrument in San Jerónimo, Tlacochahuaya. Their modern counterparts live at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary in Berkeley (built by Greg Harrold, 1989) and at Mission San José in Fremont (Manuel Rosales, 1989).

Correa’s works fall into several categories: tientos (the Spanish version of ricercars), glosas on hymns, and variations on popular songs. Like any good treatise on keyboard playing, his Facultad ranks pieces by difficulty and enters into lengthy discussions of fingering, articulation, ornaments, and other practical matters. You can pore over that information in several translations, but on this remarkable album, Bates’ expert performances of Correa’s music amount to an aural instruction book on how these works should be played. Three of Correa’s better-known pieces will serve as examples.

On the first disc, Bates plays No. 53, the “Tiento de medio registro de dos tiples de segundo tono,” and No. 69, the “Tres Glosas sobre el Canto Llano de la Inmaculada Concepción: Todo el mundo in general,” on the Oaxaca Cathedral organ.

No. 53 is a medio registro piece with two elegant treble solos that intertwine and form lovely cross relations. The Glosas feature increasingly fast divisions on a fetching popular song. Some organists give the tune a more folksy treatment, but Bates’ sprightly performance preserves Correa’s characteristic nobility.

Later, on the fourth disc, the organist offers a vibrant performance of the full-keyboard tiento, No. 16, “Segundo tiento de quarto tono a modo de canción,” a multi-sectioned work with shifting meters and delicious syncopations.

The richly-documented album insert includes photos of the colorful instruments, detailed registrations for each of the pieces, and producer and recording engineer Roger W. Sherman’s amusing remembrances of the vagaries of recording in Mexico, where the noises of crickets, barking dogs, crackling bellows, and a clock that played De Camptown Races just before the hour intruded on Correa’s music and customs agents on both sides of the border threatened to impound equipment.

This magisterial project will be of primary interest to organists and keyboardists, but anyone interested in Iberian music will find it fascinating and gratifying. One caveat: organists may be disappointed not to hear more from the trompetas, or the horizontal reed stops that project out of the front of the organ cases. Those seemingly iconic ranks came into vogue in Spanish instruments after Correa’s time, but Bates can’t resist giving them a “cameo” appearance or two. Also enjoy “toy” stops like the drum that adds a martial flavor to No. 12, a tiento on Morales’ La Batalla.

Daniel Hathaway founded ClevelandClassical.com after three decades as music director at Cleveland’s Trinity Cathedral. He studied historical musicology at Harvard College and Princeton University, and orchestral conducting at Tanglewood, and team-teaches Music Criticism at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.