by Steven Silverman

Published March 6, 2023

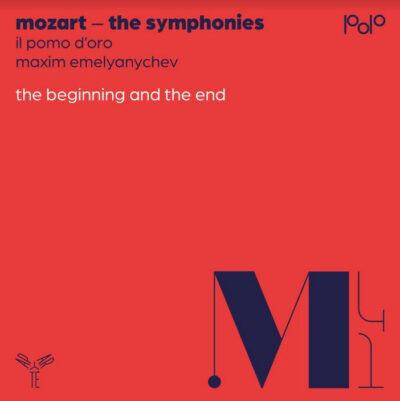

Mozart: The Symphonies (Vol 1). Il Pomo d’Oro and conductor Maxim Emelyanychev. Label Aparté, AP307

A complete Mozart symphony recording project from Il Pomo d’Oro, a crack period-instrument ensemble, and conductor Maxim Emelyanychev, is off to an auspicious start, and then some. Their plan is to pair early and late symphonies, so this initial recording bookends Mozart’s first effort, K. 16, with his last, the mighty Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”). They fill out the CD with the Piano Concerto in A Major, No. 23, K. 488.

The pairing is serendipitous. K. 16, written when Mozart was eight years old and on tour in London, has two brisk outer movements which would do credit to mature masters. The first movement already shows familiarity with then-nascent sonata form: contrasting first and second themes with modulation to the dominant, development section with the scalar opening theme played both as it first appears and inverted (potentially a naive device until one hears Mozart doing the same thing with the embroidered scale theme in the “Jupiter” finale!), and a recapitulation that commences with the second group of themes, since the opening material has figured throughout the development.

The First Symphony’s Presto finale has a catchy tune and swaggers engagingly. But the slow movement is the revelation. In the relative minor key, it begins with violins and violas playing soft, reiterated chordal triplets, with the lower strings playing subdued, slightly melodic duplets against this pulsation. The horns then enter softly with the main theme and, lo and behold, it is the theme of the finale of the “Jupiter” Symphony (C-D-F-E, transposed here to E-flat Major and later to C minor), in the same rhythm. Talk about the child being the father of the man!

This atmospheric, elegiac mood is sustained for the movement’s three-plus minutes and already is a soundworld like no one else’s. The recording does ample justice to Mozart’s maiden effort, with the ppp return of the theme in the slow movement being especially eloquent.

The “Jupiter” gets a reading that has plenty of illuminating things to say. This period band has a leaner sound than a modern orchestra, but plenty of heft when needed. The string section sounds mellower and a bit darker than a modern orchestra, reflecting use of a Classical-era bow, gut strings, and discrete vibrato; timpani is slightly coarser and with more rapid decay; winds a little more pungent; and brass (with what sound like valveless horns) also a bit more mellow. The sound of the band dissipates, or decays, more rapidly than the modern equivalent, paradoxically allowing greater scope for contrasts.

For example, sudden loud interjections do not run the risk of cluttering neighboring music. Emelyanychev is alert to these possibilities, drawing all manner of contrast and nuance from his ensemble. Textures throughout are diaphanous where, so off-beat accompanying figures in the slow movement register clearly without being obtrusive. Elsewhere hairpin crescendos and decrescendos are consistently telling without being exaggerated.

Passages we may have grown to take for granted sound new here. In the first movement, the opening flourish jumps right off the page. The initial entry of the brass and tympani is a real event, as is the ppp/ff explosion at the end of the exposition. Another nice touch in the opening movement is how the second theme dances. In the transition to the second theme in the recapitulation, Emelyanychev takes some tempo liberties—held notes and a ritard—with unusual and effective result.

The group takes the slow movement a bit quicker than one often hears, and effectively so. Particularly lovely was the minor key episode in the middle of the movement, and the oboe and flute playing in the transition back to the recapitulation. And, by playing the big chord in the movement’s opening theme as a real interjection, this familiar melody sounds dramatic and not just pretty.

The group finds plenty of contrast in the Minuet, such as the exuberant thump at the entry of the trumpets and tympani. And their trio is a delight. The reply to the ‘theme’ (merely a V-I cadence—Mozart’s little joke) is saucy and, when this material returns, the group adds both ornaments and an insouciant obligato in the flute.

The celebrated finale, with its off-the-charts contrapuntal virtuosity, gets a fleet rendition here, with voices registering clearly throughout. The bustling sound in the lower strings is especially appealing.

It bears mention that this reading richly conveys the shadows which abound in this score. Without being didactic, chromatic passages and other “purple” harmonies get noticed, sometimes by tempo gradations (as in the first movement transitional passage mentioned above) or by dynamic pointing up (such as the modulatory chords leading to the second theme group in the slow movement, and the strikingly dissonant chords in the central episode of that movement’s development section). One gets a sense of how unusual—indeed, downright strange—these passages must have sounded to their initial listeners.

The recording contains a bonus: the great A Major Piano Concerto No. 23, K. 488, with Emelyanychev as both soloist and conductor. He plays what sounds like an 18th-century fortepiano, an instrument with leather hammers, very shallow key dip, and a highly touch-sensitive and light action. There is plenty of variety in the sound, where the lower, middle, and upper registers each have distinct timbres. The sound also decays quite rapidly, which promotes non-legato as the default touch, and allows for sharp attacks that bite without harshness.

The highlight of this performance is the achingly beautiful and poignant slow movement, an exceptional piece even by Mozartean standards (in F-sharp minor to boot—Mozart’s only piece in that key). Emelyanychev plays the theme as marked, Adagio, but still manages to convey a Sicillienne feel, giving a slight lilt to the theme’s dotted figure. He draws a sweet tone from the instrument, and phrase endings are consistently and exquisitely tapered. He adds some discrete ornamentation when the theme returns, and really goes to town ornamenting the last of the large intervallic skips which occur toward the end of the movement.

After playing the first of these skips as single bare notes (as notated), he fills in the next iteration with arpeggios, scales, and trills. This works both melodically and structurally, properly making this the movement’s climax.

The final movement is taken at an appropriately fast clip. The passagework is both clean and nicely phrased. (Kudos to the bassoonist and clarinetists for negotiating this tempo in the opening tutti.) Nothing is routine. You never gets the sense of a bunch of fast notes just chugging along. And relaxing the tempo at the lead-in to the contrasting second theme provides a nice respite from the lively goings-on.

Still, Emeyanychev’s opening movement is a tad on the indulgent side. He tends to take a new tempo each time the piano plays alone—sometimes effectively, sometimes not. He really gets rolling, though, in the cadenza (Mozart’s own) where he conveys genuine drama in the scales and arpeggios that lead back to the final tutti.

In all, this recording is a splendid achievement, and a welcome harbinger of further exploration of this repertoire.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 23nd season, and for many years a resident chamber ensemble at Washington D.C.’s Phillips Collection.