by Anne E. Johnson

Published March 27, 2023

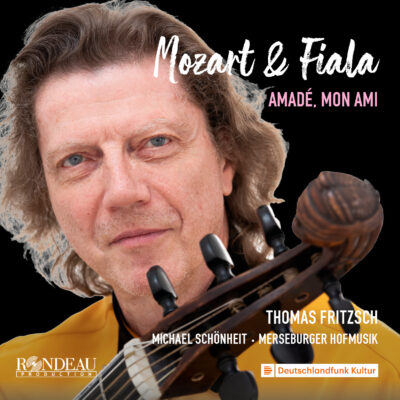

Mozart and Fiala: Amadè, mon ami. Thomas Fritzsch, viola da gamba; Merseburger Hofmusik; Michael Schönheit, fortepianist and director. Rondeau Production/Deutschlandfunk Kultur ROP6234

Josef Fiala (1748–1816) was a close friend of the Mozart family. He played with Leopold and Wolfgang in Salzburg as an oboist in the Prince-Archbishop’s orchestra. His oboe career ended alarmingly after he blew for so many hours every day that he ended up vomiting blood. Fortunately for him (and for us), he was also an accomplished viola da gambist and cellist as well as composer. In this new project by gambist Thomas Fritzsch, three of Fiala’s multi-movement works for the instrument are presented alongside some by Mozart fils.

Most of the pieces on this recording use combinations of gamba, violin, and continuo, while one is for unaccompanied gamba and one for a small chamber orchestra with strings and winds, courtesy the ensemble Merseburger Hofmusik under the direction of fortepianist Michael Schönheit. Fritzsch previously collaborated with them for his 2020 collection of rarely heard 19th-century gamba works on Coviello Classics. Although he’s now backtracked half a century, he’s still in a historical period where it’s good to be reminded that gambas were, in fact, in common use.

Fiala’s Sonata in G (ReiF 4.51), a quartet with violin, cello, and piano, is the most revelatory glimpse at the little-known composer. The Adagio second movement is a patient study in richly designed homophonic sonorities with occasional and quite surprising glimmers of dissonance. In the Rondo finale, Fritzsch maintains a light touch, never getting bogged down in the figuration. The D Major Concertino for gamba and continuo (ReiF 4.52), which opens the album, has a natural weightiness that Fritzsch counters with fluidly.

The three-movement Concerto in F (ReiF 2.65) shows Fiala to be a skilled craftsman with a charming turn of phrase and a tasteful knack for orchestration. The orchestra itself does not match that elegance, succumbing to less than precise ensemble and a tendency toward shrillness, especially in the violins. The controlled playing of French hornists Stephan Katte and Matthias Standke helps to balance the sound. Fritzsch’s solo part is accurate and expressive, even if tricky passages seem more labored than is ideal for Fiala’s elegant style.

None of the works here by Mozart were written for gamba—at least not specifically. Mozart’s B-flat Major Andantino (KV Anh. 46), for fortepiano and an obbligato instrument of one’s choice aches exquisitely. Fritzsch also claims for his own instrument a sonata universally associated with the bassoon: “Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the autograph of the Sonata in B flat Major (K. 292) and its original instrumentation,” he claims in the liner notes. Fair enough; it works well on gamba. The opening Allegro is a hair slower than it’s usually played, but that only makes it more thoughtful.

Interesting and pleasant as it is to get to know Fiala’s work, let’s be real: He’s not Mozart. There’s no point in pretending not to exhale a happy sigh each time the ingenious harmonic and contrapuntal choices of good old Amadeus take over from the perfectly respectable creations of his pal.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.