by

Published February 16, 2018

Plague and Music in the Renaissance. Remi Chiu.

Cambridge University Press, 2017. 284 pages.

By Lynette Bowring

BOOK REVIEW — The ominous pall of the Black Death lies heavily on European history. Plague brought wide and repeated swathes of societal devastation throughout the Renaissance, and its indiscriminate contagion extended deeply into all classes of a stratified society. Despite the crucial role of plague in reshaping the communities of Renaissance Europe, its reflections in broader cultural contexts largely have been neglected in scholarship. This new book by Remi Chiu, assistant professor of music at Loyola University Maryland, seeks to assess the intersections between music and the pestilential crisis of plague in these troubled societies.

Chiu contextualizes his musicological research using a broad interdisciplinary backdrop: This is a volume that elegantly unites music with histories of science, medicine, and illness, adding into the mix social and civic histories and discussions on visual art, literature, and ecclesiastical matters, where necessary. A range of primary sources from these varied disciplines support his assertion that music could serve many purposes in a society threatened by plague. Within the huge numbers of medical plague treatises, Chiu finds frequent mention of the preventive and therapeutic qualities of musical performance. However, music was not merely a diversion from a harsh world or a way to keep the spirits up when fighting contagion; it had many uses besides these therapeutic activities.

Chiu contextualizes his musicological research using a broad interdisciplinary backdrop: This is a volume that elegantly unites music with histories of science, medicine, and illness, adding into the mix social and civic histories and discussions on visual art, literature, and ecclesiastical matters, where necessary. A range of primary sources from these varied disciplines support his assertion that music could serve many purposes in a society threatened by plague. Within the huge numbers of medical plague treatises, Chiu finds frequent mention of the preventive and therapeutic qualities of musical performance. However, music was not merely a diversion from a harsh world or a way to keep the spirits up when fighting contagion; it had many uses besides these therapeutic activities.

The Renaissance medical landscape can seem bewilderingly arcane to modern eyes, but Chiu guides the reader into a world where a devastating illness such as bubonic plague was little understood and medics grappled to comprehend the sciences of infection and contagion. The disease could be heralded by mysterious astrological portents or accepted as a divine punishment from the hand of God, who also provided medicines to heal the worthy. In such a world, music had infinite potential to mediate between mankind and a little-understood killer: Earthly music could resonate with both musica mundana and musica humana (the unheard music of heavenly and human bodies), and it could support devotional rituals to appease God or supplement His provided remedies. The transmission of sound through the air and the sympathetic vibration of similar objects could also provide a route to understanding the transmission of disease.

The specific compositions Chiu engages in his study are largely from 15th- and 16th-century Catholic traditions. Of particular interest are various works dedicated to St. Sebastian, who was increasingly sought as an intercessor against plague, and whose status is analyzed in Chapter 4. The compositions discussed range from the widely recorded isorhythmic motet O sancte Sebastiane by Dufay through Milanese motets, spiritual madrigals, and works in early Venetian prints. Although solid connections between compositions and specific plague outbreaks are often difficult to conclusively prove (a point Chiu acknowledges repeatedly), detailed and imaginative readings of these works illustrate many of his major points. Generous musical examples accompany Chiu’s close analyses, and an appendix supplies full scores of additional pieces. Chiu’s second appendix compiles a list of music associated with plague, a resource that may be helpful for interested musicologists—or for performers seeking a novel theme for a new project.

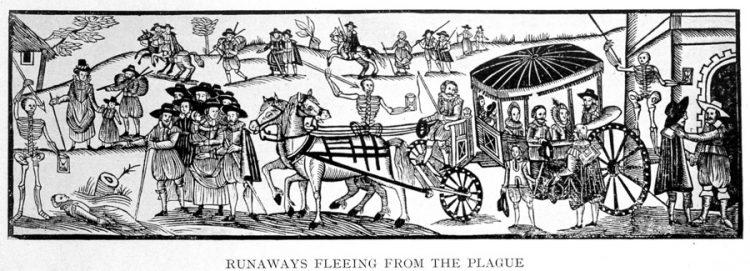

In addition to his incisive readings of selected compositions, Chiu engages more broadly with the soundscapes of plague-stricken societies, allowing the reader to imagine the profusion of sound — both ordered and disordered — that was heard in this harsh environment. Although the simple monophonies of chant, laude, and other sacred songs often receive short shrift in scholarship, where the allure of complex polyphony is strong, in this study these simple pieces support a compelling picture of fearful citizens uniting through familiar music. The second chapter details the ritualized use of music in penitential processions, where the call-and-response singing of litanies enhanced communal inclusion and cohesion.

Indeed, the attention of the church to the audible aspects of worship during a time of physical suffering demonstrates the centrality of sacred music in civic rituals. Particularly moving is an account of communal worship in Milan, where — fearing of the contagion risk in church — the pious joined together in sacred songs from their open windows and doors. Intimate, domestic, and elite settings are also considered, with the sophisticated motet being viewed as an example of discordia concors, the creation of unity from disordered parts — a concept that could optimistically act as a metaphor for the regeneration of a devastated society.

Scholarly readers will welcome Chiu’s extensive use of primary sources and sophisticated readings of the evidence, but this book is equally accessible to the non-specialist reader, who will find much to explore in its intersections between medicine, music, and Renaissance society. Although the topic of this book may seem morbid at first glance, its wide-ranging discussion of civic soundscapes and selected compositions demonstrates the tremendous power of music to lift the spirits, commune with higher powers, and unify societies in the face of suffering.

Lynette Bowring recently graduated from the Ph.D. program of Rutgers University with a dissertation titled “Orality, Literacy, and the Learning of Instruments: Professional Instrumentalists and Their Music in Early Modern Italy.” She teaches at Rutgers University and The Juilliard School.