Sometimes the most exciting discoveries are waiting to be made right in your own backyard. That was certainly the case with the Newberry Consort, a nationally known early-music ensemble in Chicago, and the little-known music of 17th-century Mexican composer Juan de Lienas.

In 2011, soprano and co-director Ellen Hargis was working on a project involving 17th-century Italian convent music when one of her students at the University of Chicago startled her. He mentioned the existence of six nearly unknown choir books from a Mexican convent in the collection of the Newberry Library, the independent research library in Chicago where the musical ensemble was formerly in residence. (She suspects at least two others are lost because there are missing sections from some of the works they contain.)

In 2011, soprano and co-director Ellen Hargis was working on a project involving 17th-century Italian convent music when one of her students at the University of Chicago startled her. He mentioned the existence of six nearly unknown choir books from a Mexican convent in the collection of the Newberry Library, the independent research library in Chicago where the musical ensemble was formerly in residence. (She suspects at least two others are lost because there are missing sections from some of the works they contain.)

“He and I went to the library to take a look at these, and we were just blown away,” Hargis said.

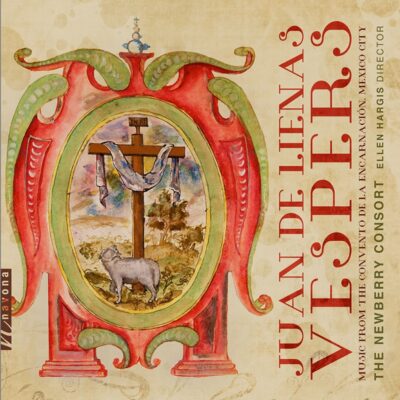

That encounter set Hargis and the Newberry Consort on an ongoing Mexican musical exploration that has included performances, including Mexican Christmas programs, and a live concert recording. The most recent chapter in this continuing odyssey was the Navona Records release in February of an all-female album titled Juan de Lienas: Vespers, Music from The Convento de la Encarnación, Mexico City. “Once we got into it,” she said, “we just kept going down that road.”

The recording features Hargis’s reconstruction of what vespers — an evening prayer service — might have been like at the Mexican convent, which was established in the late 16th century and ended sometime in the 19th. Included are the essential components of such a service: a selection of psalms with antiphons, hymns, and a Magnificat (Song of Mary)—12 tracks in all. Nearly all of the music was written by Lienas (1617-1654) around 1630 with several additions by other composers, including Quinto tiento de medio registro de tiple de séptimo tono, a kind of organ interlude by Francisco Correa de Arauxa, a priest, composer, and organist in Seville in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Since the rise of the period-instrument movement in the 1960s and 1970s with groups like the Academy of Ancient Music in England, most of the focus on music from the Baroque period and earlier has been centered on Europe. But increasingly, scholarly and audience interest has grown in music from elsewhere, especially parts of the Spanish Empire, including New Spain, one of four viceroyalties in the Americas. That vast region existed from 1535 to 1821 and included the entirety of what today is Mexico. “Mexico is opening up its archives and libraries, and convents and monasteries are releasing their music, and scholars are eating it up,” Hargis said. “It’s a hot field.”

While Baroque music from the New World was solidly rooted in the European aesthetic, it was typically slightly behind the prevailing trends simply because of its geographical distance from the traditional musical centers, and it was tinged by local folk music and other idiomatic influences. “It’s very European, but with Latin rhythms that you don’t expect, so it’s an extra touch that is very exciting,” said Italian-based mezzo-soprano Candace Smith, one of 10 singers and four instrumentalists (one participant played baroque guitar and sang) who took part in the recording. She also noted the music’s emphasis on the guitar and bajón (an early bassoon) and its division of vocal parts, all elements that are different than, say, Italian convent music of the same time.

Hargis decided to assemble a vespers program to take advantage of the abundance of such music in the choir books, and she spotlighted Lienas because of the high quality of his writing and the plenitude of his compositions in the tomes. Very little is known about the composer, but he was born in New Spain and is believed to have come from the upper classes with a good education. “I really loved his kind of combination of old-style music and new-style music,” Hargis said. By old style, she means music in the vein of Palestrina with “beautiful, mellifluous polyphony,” and new style refers to the “really jazz, rhythmically infectious” inflections in the music reflecting the folk influences surrounding the composer.

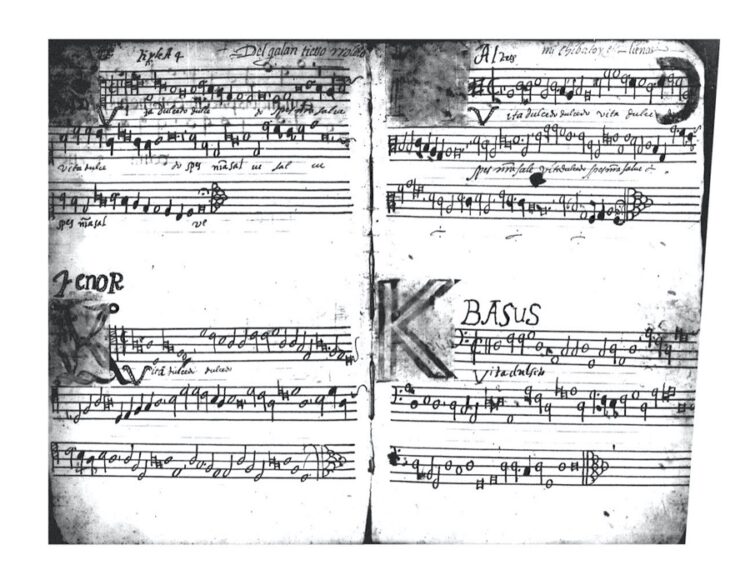

Early music almost never arrives from the past ready for the concert stage. It inevitably requires detective work to uncover in the first place and more investigation to fully understand all its components. Then come the often-laborious editing and preparation necessary to make it ready for performance, including transforming it into modern notation. The music in the choir books is divided into individual parts, so Hargis had to create a full score for each work, allowing the singers to view all the parts at the same time, the configuration that contemporary performers prefer.

In addition, she chose to pick antiphons to go along with the psalms (ones that matched the modes and suited the texts) — the typical way the two would have been presented during services but are not always heard in concert presentations of the vespers. “I really like hearing those moments of plainsong that introduce each beautiful, intricate psalm,” Hargis said. “It’s like having a little palate cleanser between these very rich, dense pieces.” Not added for the most part was ornamentation. That is a common ingredient in many Baroque performances, but it is typically not used in layered choral music. It was only inserted here in a few solo vocal lines in works like the “Magnificat a 10.”

Vespers usually begin with the psalm “Deus in adiutorio meo,” and Hargis opens the recording with a setting titled “Deus in adiutorio a 5.” Since the name of the composer was cut off of this version when the choir book that contains the work was rebound in the 18th century, its origin is not clear. But because of its location alongside other works by Lienas and the fact that the style is consistent with his writing, Hargis felt comfortable attributing the work to him. The album ends with a setting of “Salve Regina” she described as “exquisite.” It is one of the composer’s best-known pieces because it can be found in both the Newberry choir books and a manuscript in Puebla, Mexico, and it was included some decades ago in an anthology of music from New Spain.

Frances Conover Fitch, an organist from Gloucester, MA, who performs on the recording, helped with some of the preparation of the music, creating a bassus generalis, or through bass line, for the works, a necessary yet missing component that was probably in the choir books that are lost. “They would not have had men singing in the convent,” Fitch said, “so they had to find some way of doing it [the bass line], and there might well have been women with very low voices. They exist. And if there weren’t, it could be played by the instrumentalists, that lowest line.” On this recording, the bass is sometimes performed up an octave by the singers or voiced by the instrumentalists. In addition, Fitch added some organ solos to the vocal pieces, a not uncommon practice at the time, including some versillos by an anonymous 17th-century Spanish composer inserted into the Magnificat, which she and Hargis reconstructed.

One of Hargis’s most fascinating discoveries were the sometimes phonetic spellings of the Latin texts in the choir books. Latin is inevitably pronounced slightly differently by speakers of various modern languages, and whether by design or simply because the scribes who notated the music didn’t know how to correctly spell the Latin, the spellings in the books provide important clues as to how the nuns pronounced the words in the ancient language. And the Newberry Consort tried to follow those indications for this recording. “I know I’m a total geek about this stuff,” Hargis said, “but this is like breadcrumbs from the past.”

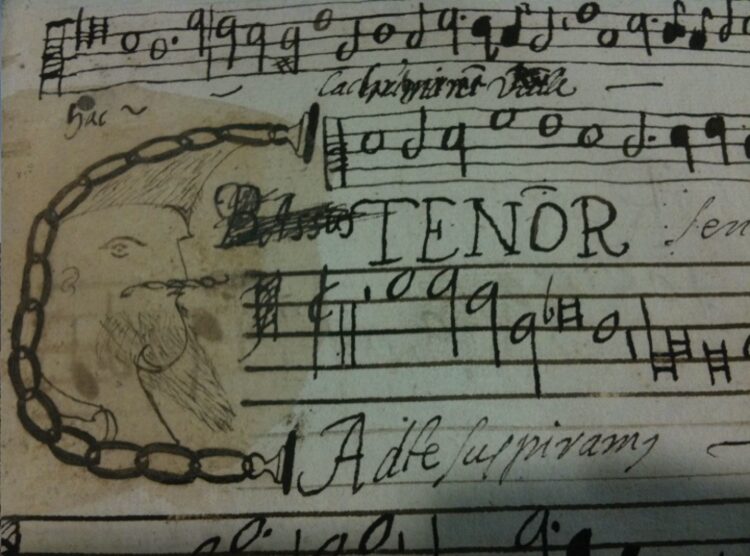

Hargis was also charmed by the “fun, little tidbits” found on the margins of the choir books — markings, notes, and even doodles or graffiti, including insults and less-than-flattering caricatures of Lienas, who was apparently not always well liked by the scribes. “It’s so human,” Hargis said. “It’s not like those fancy medieval manuscripts with gold and nobody ever touches them. These were working books.”

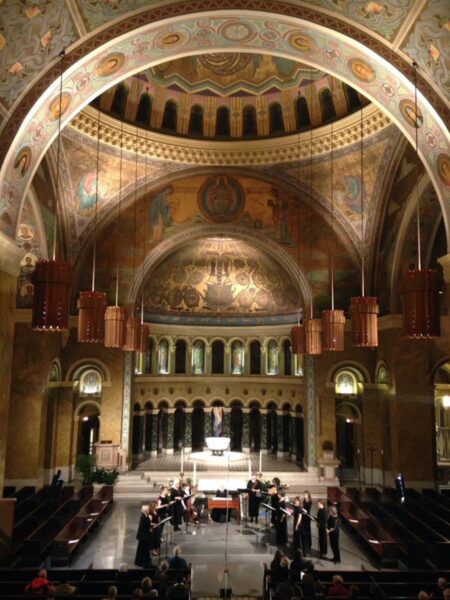

The recording took place in 2019 in Chicago’s St. Clement Church, which was chosen for its fine acoustics and what Hargis called the best chamber organ in the city — a movable, five-stop instrument built in 2005 by Taylor & Boody Organbuilders in Staunton, VA. Hargis picked singers she had worked with before, including some former students, and ones she knew by reputation. She wanted a mixture of vocal types because the singers at the convent were there due to shared religious convictions and not their vocal unity. “I really didn’t want this kind of English choral style — a super-homogenous blended sound — but something that I thought was more historically accurate,” Hargis said.

Fitch, who has collaborated with the Newberry Consort for at least a dozen years, called the experience a celebration of singing and the artistic prowess of the nuns, and she described it as “tremendously fun.” Growing up at time when women were all but excluded from reference books about classical music, she said, “I love the idea of doing music that was either written by or for women.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.