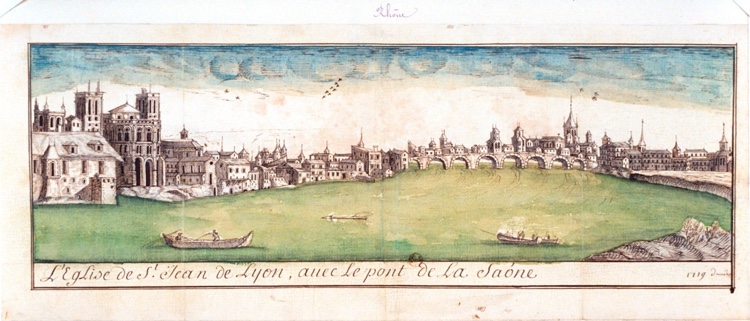

The early 1690s were not a happy time for France, and especially for the city of Lyon. A harsh winter and months of famine crippled the city in 1693. That spring, crowds of frustrated Lyonnais demanded government assistance in supplying wheat for the people. Despite the pressure of this and other protests that erupted across the country, the Crown did little to alleviate the people’s suffering. Matters worsened the following year, when thousands of Lyonnais succumbed to an epidemic (likely typhoid) that would claim some one million souls as it raged across France.

Despite the chaos that gripped the kingdom, Louis XIV continued to drag France through the seemingly endless Nine Years’ War (1688-1697), which played a heavy toll on the lives and morale of the people of Lyon. As one unhappy member of the nearby parish of Saint-Jean-des-Vignes reflected, “The year 1694 was one of the deadliest and most miserable years that had ever been seen.”

Unsurprisingly, music in Lyon suffered acutely during this period. On January 1, 1693, the city’s professional opera company, known as the Lyon Académie de Musique, declared bankruptcy and shut its doors. It was not until 1695 that Jean-Pierre Leguay, who had founded the Académie in 1688, was able to bring the company back into business. We have regrettably little documentation about how musicians supported themselves, both financially and emotionally, during what must have been an agonizing two-year hiatus.

One darkly humorous comedy from the period, Marc Antoine Legrand’s La chûte de Phaëton (Lyon, 1694), notably offers a rare glimpse into the consequences of the Académie’s closure: Throughout the play, characters representing laid-off Académie singers, instrumentalists, and dancers lament their loss of salary, their inability to pay back loans, and, in the words of one frantic tenor, the “hunger that devours them.” Though fictional, the play gives an idea of the distress that Lyonnais musicians experienced as they faced job loss amid a background of contagion, disastrously erratic weather, and war.

The late 17th century may seem a distant past, but the trials that the Lyon Académie experienced are strikingly resonant with the onslaught of crises we face in 2020 as musicians, musical organizations, and the world at large navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, social and political upheaval, and economic recession.

Indeed, we can take away several lessons from the Académie and its process towards economic and artistic recovery. How did Académie musicians transform hardship into productive creativity? How did they assert their relevance in the local community? What worked — and what didn’t? The answers to these questions could fill a book, but we can break them down into three key takeaways: vary repertoire, embrace humor, and think long-term. Though not immediate solutions to the difficulties that musicians currently face, these lessons can at least spark conversations about what we should continue doing, and what we should begin doing, as we push forward.

Shake up your repertoire

When the Lyon Académie opened in 1688, it filled its seasons exclusively with the operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully for well over a year. Lully’s operas were a novelty in Lyon: The composer, who more or less invented French opera under Louis XIV, had prohibited operas from being performed in France without his oversight, so it wasn’t until after his death in 1687 that most of the kingdom finally saw his stage works. But by the end of 1689, Lully’s operas failed to reap the revenue the Académie needed, and the institution spiraled towards bankruptcy. When Leguay finally resuscitated the Académie in 1695, he shifted away from the company’s old chestnuts, incorporating newer works from Paris as well as repertoire by local librettists.

Thanks to resources like EMA’s Resources for Diversity in Early Music Repertoire, we increasingly have at our fingertips the opportunity to explore neglected works by a diverse array of composers. As we embrace previously unexplored repertoire, we can also reflect on how to challenge our perspectives and assumptions about more familiar works. An ensemble could highlight certain instrumental pieces from Handel’s operas, for instance, as works originally performed by female dancers to promote conversations about the role of women artists in the Enlightenment.

Varying repertoire or the way we present it is admittedly easier said than done; it can be risky to set aside guaranteed crowd-pleasers for lesser known works, especially in a gig economy that does not necessarily promise musicians secure income. While the Lyon Académie did not drop Lully’s operas wholesale from its programs after 1695, its swift and ultimately successful decision to commit to a wider repertoire set a precedent for the long-term value of a broader musical scope.

Make fun of yourself

The playwright Marc-Antoine Legrand (1672-1728) went beyond representing out-of-work musicians in his comedies. His works also poked fun at the business of opera, featuring characters such as diva sopranos, a financially incompetent opera director, and a haughty dancer who bullies his colleagues. After the Académie was up and running again, the company took Legrand’s cue and offered repertoire that bubbled with self-referential humor.

In one comedy, for example, a character complains at length about the Académie’s recent production of Lully’s Armide and the cacophony of its screeching sopranos. Other works gently ridiculed the Lyon community, featuring such characters as starry-eyed opera fans or — in another work eerily resonant with the 2020 pandemic — a group of people who fall victim to a charlatan cure for disease.

By featuring repertoire that light-heartedly mocked its raison d’être, the Académie encouraged a sense of empathy and connection from its audiences. Moreover, by parodying spectators with good humor, the Académie gave audience members the opportunity to laugh at their mistakes as they navigated the challenges of the tumultuous world around them.

We also can embrace humor in our programs today. Organize a virtual production of an opera parody, invite others to sing along to some swashbuckling catches over Zoom, or pull out those onomatopoeic madrigals for a virtual collaboration. It is an especially good time to create a pastiche of repertoire that makes fun of the art of historically informed performance. How can we invite friends and audiences to laugh with us as we struggle with our fickle gut strings, our love-hate relationship with the crumhorn, or the headaches we have all experienced in collaborating with a group of people to organize a performance?

Framing the challenges of early music performance in levity encourages audiences — and performers — to connect with the repertoire while providing a therapeutic space for everyone during a time that feels all too marked by tragedy.

Think long-term

The Lyon Académie successfully emerged from bankruptcy to enchant audiences throughout the 18th century, albeit with many hiccups along the way. One of its main successes was winning support from city leadership, a benefit that assumed various forms over time, from the municipally funded construction of an opera house to the less tangible ideological commitment to the Académie as a means of upholding the “greatness” of the city. We should take comfort in the fact that, three centuries ago, the Académie faced similar struggles to what we are experiencing today, and that it eventually overcame these struggles through perseverance, innovation, and local support.

The hiccups that the Académie experienced as it continued to operate over the course of the 18th century, however, should also give us pause. Leguay lost and regained directorship over the Académie four times during the course of his 34-year career, primarily due to financial difficulties that continued to afflict the Académie. Unfortunately, many opera companies in early modern Europe were victim to fiscal hardship; as the COVID-19 pandemic has made woefully transparent, musical organizations continue to experience difficulties in achieving sustainable support.

Beyond thinking long-term, we need to remember long-term. We need to remember that history can repeat itself: We are facing struggles similar to those an opera company encountered 300 years ago. How can we work to prevent musicians from facing such difficulties again? Now more than ever, early music ensembles should pursue opportunities to engage with local leadership, whether it be arts councils, municipal leaders, or other advocates, to articulate the vital role that early music can play in teaching audiences how to engage with the world with creativity, inclusivity, and joy.

Early music performers excel at learning from the past to make great music today. Let’s continue taking lessons from the past — not just to integrate them into our performance practice, but to apply them to finding dynamic, meaningful, and sustainable ways of sharing the repertoire we love with others.

Natasha Roule holds a Ph.D. in historical musicology from Harvard University. She writes on the interplay of politics and opera in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly the tragédies en musique of Jean-Baptiste Lully, and has taught at Aquilon Music Festival and George Mason University. She is preparing a critical edition of Marc Antoine Legrand’s La chûte de Phaëton (1694).