by

Published June 23, 2017

Bach and God. Michael Marissen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. 257 pages.

By Raymond Erickson

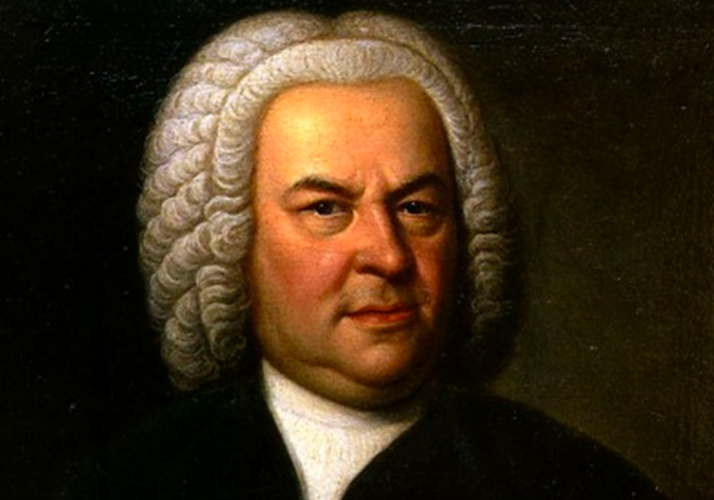

BOOK REVIEW — The scholarship of Michael Marissen has always been characterized by depth of research, fearlessness, and a tendency towards considerable speculation. Those qualities are found in the work under review, a compilation of seven of his essays dealing with religious issues in the music of J. S. Bach.

The author states that he is not interested in Bach’s personal religious views, yet the material is presented so that we associate the issues raised in the book with Bach himself, rather than, say, the authors of the libretti he set to music. Moreover, I suspect that many readers will be drawn to this book (as have writers for the New York Times, for example) by their interest in the question “Was Bach an anti-Semite?”

The author states that he is not interested in Bach’s personal religious views, yet the material is presented so that we associate the issues raised in the book with Bach himself, rather than, say, the authors of the libretti he set to music. Moreover, I suspect that many readers will be drawn to this book (as have writers for the New York Times, for example) by their interest in the question “Was Bach an anti-Semite?”

Marissen’s consideration of Bach and Judaism takes up Chapters 3-6. Framing this are two insightful and original opening chapters dealing, respectively, with basic Lutheran beliefs as expressed through Bach’s music and with texts whose theological meaning Marissen believes are not properly understood today — and a final chapter on the author’s religious and theological interpretation of The Musical Offering.

Cantata BWV 46, “Schauet doch” (Chapter 3), offers the example of Jerusalem’s destruction as a lesson to Bach’s Lutheran congregation that they must reform and repent, lest they too suffer God’s wrath: the cantata’s second half emphatically ends with the chorus — representing sinful Christians — pleading for God’s mercy for their sins. However, Marissen shifts the emphasis to the first recitative and those “that one at present hears Christ’s enemy blaspheming in you.” But this brief, implicit condemnation of contemporary Jews (by the librettist, it should be stressed) needs to be balanced against the facts that Catholicism and Islam are directly attacked in Cantatas BWV 18 and 126 and that the word “Jews” occurs in only one (BWV 42) of Bach’s almost 200 sacred cantatas. Moreover, none of the texts by the anti-Semitic Erdmann Neumeister that Bach set have anti-Jewish content.

As for the St. John and St. Matthew Passions (Chapters 4-6), Marissen points out that the aria and chorale texts, which Bach might have had control over, contain no anti-Jewish sentiments. On the other hand, Marissen forthrightly addresses the vitriolic anti-Judaism of St. John’s Gospel, especially its use of the epithet “the Jews.”

In the end, what is striking is that, given the oppression and denigration of the Jews that existed at Bach’s time and the interest in the topic in our time, no unquestionable evidence of anti-Judaism on Bach’s part is adduced. Moreover, Marissen’s major sources (including, to be sure, books Bach owned by Luther, Abraham Calov, Heinrich Müller, and Johann Olearius) date from the 16th and 17th centuries.

Therefore, a genuine limitation of the book is the lack of attention to the contemporary, real-life context of Bach’s Leipzig at the cusp of the Enlightenment: when Leipzig University theologians defended the Jews against the blood libel; when a 1734 legal disputation stated that attacks on Jews from the pulpit were largely over; when Freemasonry, with its ideals of social and religious equality, attracted members of Bach’s circle (and perhaps Bach himself); when Jews began, slowly but steadily, to win the right to live in Leipzig after banishment in the 16th century; and when Bach, a fervent Lutheran, found himself a servant of a Roman Catholic King-Elector — Catholicism being potentially a greater threat to Lutheranism than either Judaism or Islam.

If these and similar elements are incorporated into the partial picture of Bach’s situation Marissen has often brilliantly and learnedly drawn, we will have an even better understanding of Bach and God.

Raymond Erickson, director of the annual “Rethinking Bach: A Performer’s Workshop” (www.rethinkingbach.com), recently performed an all-Bach harpsichord recital in Beijing’s Forbidden City Concert Hall.