In recent months, a national spotlight on systemic racism has given rise to conversations about the need for immediate and visible inclusivity in the early music field and its repertoire. The recently published Inclusive Early Music project captures the imagination, presenting resources that offer glimpses into what a more inclusive field could look and sound like. In a recent conversation, Giovanni Zanovello and Erika Honisch, editors of the project, spoke about the nuanced process of creating a resource that prioritizes inclusivity and the tensions inherent in pursuing a long-term project to serve a field with pressing needs.

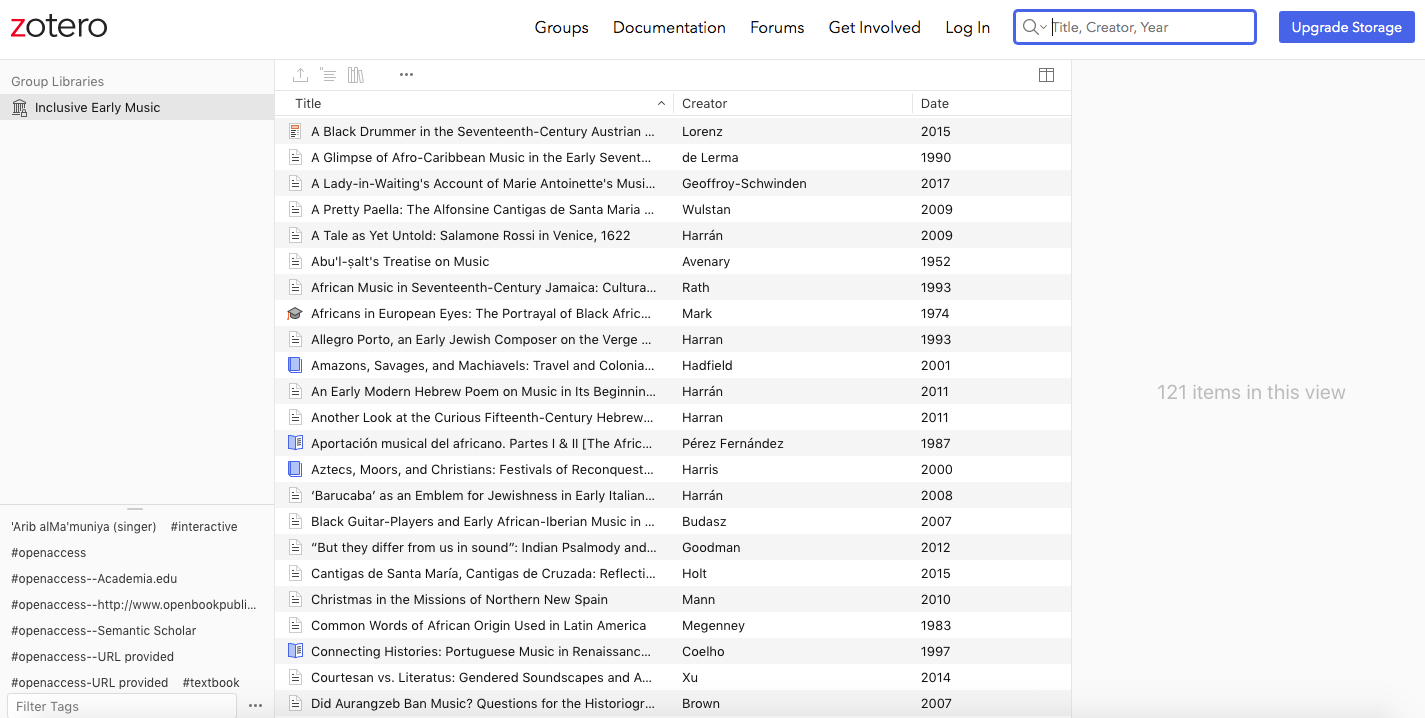

The Inclusive Early Music project’s most comprehensive resource is a bibliography cataloguing more than 100 scholarly articles that focus on “the variety of contexts in which ‘Early Music’ happened, with special attention to people who—because of race, gender, geographical origins, or social status—have been left out of the mainstream musicological narrative.” The bibliography includes sources that explore music-making both outside of Europe and by marginalized peoples within Europe. Many sources also focus on ways in which diverse musics were shaped by cultural encounters.

The project grew out of a discussion among Zanovello, Honisch, and a few colleagues over breakfast six years ago at a meeting of the American Musicological Society. Everyone at the table taught survey early-music history courses, and they identified a shared frustration. “We were very much aware that we were teaching a restricted narrative,” said Honisch, associate professor of history/theory at Stony Brook University’s Department of Music. “It turned out that everyone who taught these surveys was hitting the same kind of limits, and we’re teaching classrooms that have never been more diverse.”

As the conversation continued, Zanovello, Honisch, and their colleagues discovered that they each knew of two or three different scholarly articles on inclusive topics. They decided to pool their knowledge and formed an “informal, ad hoc collective.”

In order to grow the bibliography to 100 articles and develop a framework that would facilitate its continual expansion, the collective had to think creatively about how to overcome existing limitations. Zanovello, associate professor of music at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, pointed to the “difficulty of locating research on particular themes,” which he partially attributed to meager search results on inclusive topics in today’s most utilized musicological databases. In addition to the limitations of existing sources, Zanovello and Honisch acknowledged that the current bibliography reflects its creators’ areas of expertise, English-speaking majority, and background in working with textual sources.

To continually broaden the scope of the bibliography, the collective designed a platform through which scholars can submit their own work on inclusive topics in early music. Since the project’s publication in August 2020, more contributions have been submitted than this small team could possibly keep up with. “We only have 100 [articles]; it could be 1,000, and we have a to-do list that makes my hair turn gray,” said Zanovello. “But it’s exciting. There’s a lot of work for us to do in the future.”

Once a corpus had been compiled, the collective grappled with how to construct their bibliography in a way that would make it inclusive and accessible to as many people as possible. Existing tools once again proved inadequate. “We were loosely thinking about what form this would take over the years,” said Honisch. “At some point, the format of an Oxford bibliography came up. Those are wonderful, they’re critical, but they’re not as malleable and flexible, and they’re not open-source.”

The collective eventually decided to implement and format their bibliography using open-source reference management software called Zotero, which would allow them to categorize the articles in their corpus using tags they created. They discovered that many pre-existing tags were “very user-friendly, very library-friendly, but maybe, as it turns out, not very equitable,” said Honisch. Creating their own tags slowed their progress considerably, but Honisch said it is a trade-off they are willing to accept in order to better “think about how tags can represent points of view or biases.”

Finally, the collective had to consider accessibility at the level of individual articles. Though it proved to be more time-consuming, the collective intentionally sought out articles that were not behind paywalls. “We try to include an open-source link whenever possible,” Zanovello said. “We even have an open-source tag. If you click on that tag, you only see open-source materials.”

For the project “to be useful in any possible way, unfortunately it cannot be rushed,” said Zanovello. He and Honisch struggled with the tensions inherent in creating a comprehensive and perpetually evolving tool for a field with urgent needs and were quite conflicted about publishing the project this past August, recognizing the many ways in which it remains incomplete. “We were not ready,” said Honisch, “but we thought it’s high time that we got this out there, and if we do it transparently, then people can kind of watch as it develops. We’re so used to only putting out the perfect final thing, and I think that gets in the way of breaking down these barriers.”

The publication has been met with both praise and pushback. Some have criticized the bibliography for how much it does not include. Zanovello and Honisch gratefully accept the criticism. “Embracing a stance that welcomes critique is also a way to push for systemic change, because systems tend to defend themselves,” Honisch said. Perhaps such critiques even speak to the project’s effectiveness as it aims not just to expose existing sidelined research, but also to “show how much is missing,” Zanovello said.

Honisch and Zanovello hope the scope of this project will be unrecognizably broad in a decade. “I envision a database that no one language dominates,” said Honisch, “not just that the bibliography itself is reflecting this rich array of scholarship that we couldn’t possibly even imagine yet, but that our colleagues all over the world are contributing so the collective is really hundreds and hundreds of people.”

Zanovello emphasized the role that the project’s decentralized format might have in future permutations. “Anyone can download the whole library,” he said. “You could drag everything into your own Zotero library and just keep going. I wouldn’t have anything against it. The idea is that this needs to be done, and I hope it will be very different in 10 years.”

In addition to the bibliography, the project features a platform through which instructors can submit lessons or assignments that frame topics in early music in a more inclusive way. Eventually, the collective imagines there will also be a way for performers to submit programs designed around inclusive themes.

Much of the scholarship in the current bibliography was actually published decades ago, yet the repertoire with which it engages is rarely, if ever, included in today’s early-music programming. Going forward, what will it take for this kind of scholarship to travel from a bibliography to a concert hall? Honisch believes digital crowdsourced tools like Zotero will play some role in expediting the process. “We’re at a moment where we can build tools together and publish things that 20 years ago would have taken years to collect and put it into a printed book that would have sat on a library shelf,” he said.

However, despite the opportunities that technologies present, Zanovello and Honisch still see long-term change as residing with the individual. They often think about their students’ futures as performers and take seriously their opportunity to shape the way students engage with and frame repertoire. “Through music teachers taking this moment, taking the plunge, and changing things up — that’s how it will get to the concert hall,” said Honisch.

Above all else, both view the Inclusive Early Music project as a continually evolving tool rather than a one-and-done solution. “This doesn’t save the world,” said Zanovello. “Everyone has to do their part.”

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and recent graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music (MM ’19). In addition to singing with numerous ensembles, she co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle.