by Andrew Willis

Published December 12, 2022

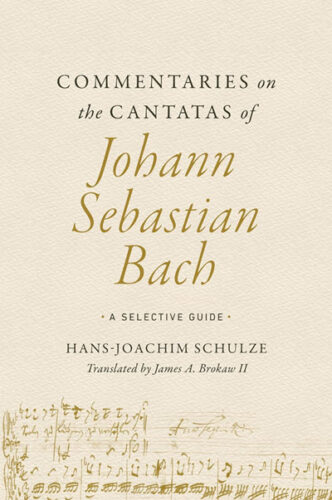

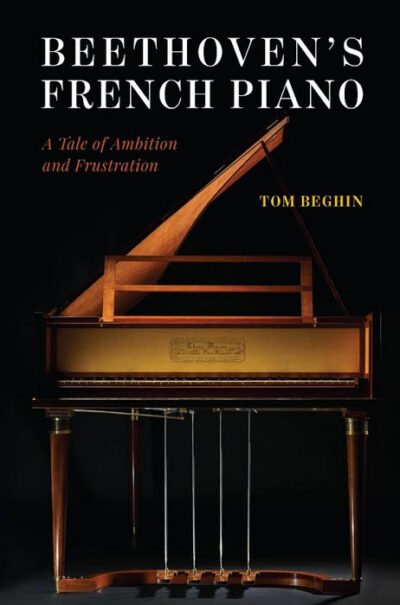

Beethoven’s French Piano: A Tale of Ambition and Frustration by Tom Beghin. University of Chicago Press, 2022. xxi + 410 pages.

When a leading fortepianist-scholar teams up with a world-renowned piano builder plus experts in various scientific and technical fields, and a group of talented and curious students to investigate every imaginable artistic significance of the Erard fortepiano Beethoven received in 1803, the results are revelatory.

In this book, Beghin recounts the research project in which, with the backing of the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium—where he’s a senior researcher—he pursued an unfettered multi-year inquiry into the least studied of Beethoven’s personal instruments, the grand fortepiano en forme de clavecin received from Erard Frères in 1803.

In this book, Beghin recounts the research project in which, with the backing of the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium—where he’s a senior researcher—he pursued an unfettered multi-year inquiry into the least studied of Beethoven’s personal instruments, the grand fortepiano en forme de clavecin received from Erard Frères in 1803.

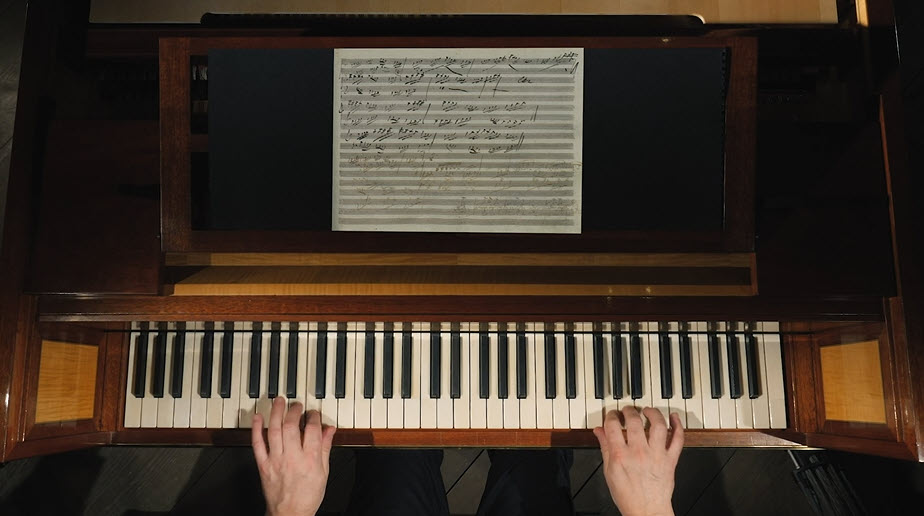

Beghin and his team devised a multitude of ways to investigate Beethoven’s Erard, starting with the indispensable element: the piano itself, in a meticulous reproduction by the Belgian builder Chris Maene. Maene succeeded in his goal of creating “a historical instrument as it was when new in the past.” It became Beghin’s primary instrument over an extended period, enabling him to personally retrace Beethoven’s path of discovery, experimentation, and creation, prompted by a piano very different from any he had previously known.

Beghin adroitly organizes multiple lines of inquiry within this volume. Preliminary chapters define the questions to be investigated and establish a secure philosophical foundation for the research. As the story develops, Beghin repeatedly and intentionally imagines himself in Beethoven’s place, desiring a French piano, being forced to endure a period of waiting and anticipation until the piano arrives, trying out its feel and sound, and realizing how many new skills of playing and hearing it both demands and enables.

The stages by which the investigation proceeded are recounted, with detailed analyses of the physical and sonic functionality of the Erard design and, importantly, its impact upon the perceptions and responses of the player. Midway through the book, the focus shifts to Beethoven the composer and his exploitation of the new affordances of his French piano. The final chapters relate a side-by-side comparison between the Maene replica and the original Erard and outline the goals and choices made while recording Beethoven’s so-called “Erard” sonatas (Op. 53, 54, and 57). Interspersed at various points in the book are four “Vignettes” in which Beghin’s collaborators Tilman Skowroneck, Robin Blanton, Michael Pecak, and Chris Maene provide background through translated primary documents and a personal interview.

The many-pronged thrust of this investigation leaves no imaginable connection unexplored. The world in which the Erard piano came to exist is brought to life from many angles: among others, a vicarious visit to the Erard workshop of 1802, the multiple sonic effects enabled by the four pedals (particularly the swelling and diminishing of tone through the una corda pedal), the “continuous sound” prized at the fledgling Conservatoire de Paris, and Beethoven’s vexed relationship with Daniel Steibelt.

Beghin develops many insightful analyses with regard to the music Beethoven composed on the Erard. He reveals the piano as a subject of composition in itself (particularly in Op. 53), explores the inherent tension between the verticality demanded by the action design and sonic response of the piano versus the horizontal perspective required by a cohesive sonata structure, and defends a plausible theory concerning the original formal conception of Op. 53 as a three- (and potentially four-) movement sonata.

That the tale ends in “frustration” during the composition of Op. 57 is revealed to be Beethoven’s own fault for having ordered extensive revisions to the action. Though aimed at making the touch lighter, the deeply invasive changes eliminated the French-touch response the composer had found stimulating in the first place.

In book’s preface, Beghin urges the reader to access www.BeethovenErard.com in order to “document this research in a more direct way than prose ever could.” I heartily second this advice. Hearing and seeing the piano played, viewing the behavior of the action in ultra-slow motion, observing the four pedals in use, sensing the excitement and deep concentration of the Maene artisans through a documentary of the replica’s construction, together with many more enhancements to be found there, will carry the importance of this project home to the reader with irresistible impact.

In addition, the ultimate stage of appreciation for the artistic results of the research project can be realized by obtaining and hearing the recording (available on the Evil Penguin label as EPRC 0036 Beethoven and His French Piano) where Beghin as performer stands behind his interpretive conclusions. In addition to Op. 54 and 57, the program includes Beghin’s hypothetical “Grande Sonate” version of the Waldstein in four movements, as well as sonatas by Steibelt and Louis Adam.

Beghin exhibits his research discoveries with total commitment, imbuing every moment of his playing with vital conviction to produce a Beethoven unlike any you’ve heard before.

Anyone who has realized new musical insights while playing a historical instrument will enjoy this fascinating narrative of a passionately dedicated, rigorous, and imaginative research project and the insights it has reaped from the study of an iconic instrument. Tom Beghin and his team have opened new vistas to our eyes, ears, and fingers.

Andrew Willis is known as a performer on pianos of all periods. He was educated at Curtis, Temple, and Cornell University, and is a professor in the UNC Greensboro School of Music.